The Eaglet air-launched drone developed by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems (GA-ASI) has flown for the first time. The company hopes that the Eaglet concept will be able to bolster and extend the capabilities of the drone’s launching platforms, with the goal of ultimately having multiple Eaglets operating in networked swarms.

A GA-ASI press release says that the Eaglet took its inaugural flight as part of a demonstration held at the Dugway Proving Grounds in Utah on Dec. 8, 2022. The Eaglet was launched from an Army-owned MQ-1C Gray Eagle Extended Range (ER) drone. The flight was jointly funded by GA-ASI and the Army Combat Capabilities Development Army Research Laboratory and Aviation & Missile Center.

“The first flight of the Eaglet was an important milestone for the GA-ASI/U.S. Army team,” said GA-ASI President David R. Alexander. “Eaglet is intended to be a low-cost, survivable UAS with the versatility to be launched from a Gray Eagle, rotary-wing aircraft, or ground vehicles. It enables extended reach of sensors and increased lethality while providing survivability for manned aircraft.”

GA-ASI also said that “Gray Eagle can carry Eaglet for thousands of kilometers before launching it while being controlled through unmanned-unmanned teaming or as a component of advanced teaming command and control concepts.”

At the 2022 Special Operations Forces Industry Conference in Tampa, Florida, GA-ASI revealed that the reusable Eaglet drone weighs less than 200 pounds, and has a span of 10.5 feet with its pop-out wings deployed. The drone can fly at a maximum airspeed of 115 knots, has a range of about 435 miles (or about eight hours with a payload of around 20 to 30 pounds), and its maximum service ceiling is about 15,000 feet.

Eaglet also clearly has low observable features that would increase its own survivability and better allow it to operate in areas without the enemy knowing it is there, under certain circumstances. The War Zone published a detailed report on this unveiling, which can be read here.

However, the existence of Eaglet, though it didn’t have a name at the time, was first disclosed by GA-ASI in 2021, as we also covered in this past story. The company introduced the concept as a way to extend the capabilities of existing manned and unmanned systems, with its flagship MQ-9 being a prominent example. Eaglet could thereby boost the survivability of its launching platforms by allowing them to still perform their reconnaissance and strike missions while at a safe distance from adversarial integrated air defense systems.

GA-ASI seems, at least right now, to be primarily pitching Eaglet as an option for the U.S. Army’s Air-Launched Effect (ALE) program that is working to establish a new family of air-launched multi-purpose unmanned aircraft. This is in addition to GA-ASI’s initial hopes that Eaglet would be able to support the operations of its well-established unmanned platforms, like the MQ-9 Reaper and MQ-1C, which have had their relevancy in future high-end conflicts called into question.

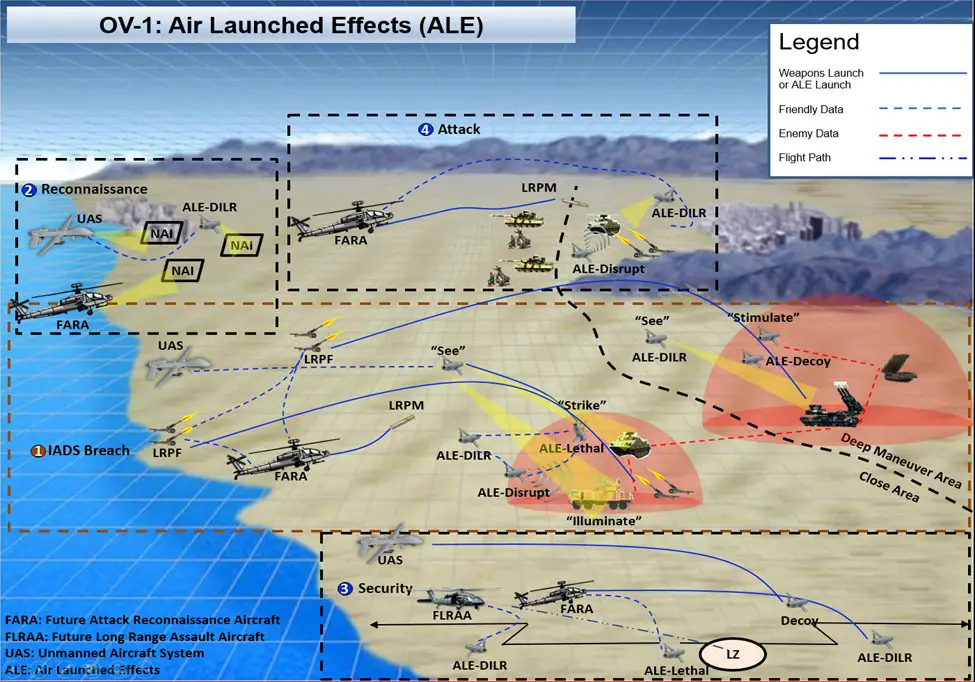

The ALE initiative was launched in 2020 and seeks to develop and field a family of systems (FoS) that, like Eaglet, can be launched from larger manned or unmanned platforms. Another defining goal of the effort is making sure that these ALE drones are capable of working together as networked swarms to perform a variety of missions ranging from intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) to electronic warfare and conducting strikes.

It’s worth noting at this point that not all elements of an ALE swarm have to be able to perform the same tasks. They could distribute functions, with some acting as scouts, some as jammers, and some as munitions, for example.

“The ALE FoS extends the tactical and operational reach and lethality of manned assets, allowing them to remain outside of the range of enemy sensors and weapon systems while delivering kinetic and non-kinetic, lethal and non-lethal mission effects against multiple threats, as well as, providing battle damage assessment data,” the Army has explained.

ALE drones will belong to either “large” or “small” size categories. The Army’s description of large ALE types, which GA-ASI said Eaglet falls under, covers those that weigh no more than 225 pounds, though less than 175 pounds is the goal. The service wants large ALEs to be able to fly at speeds of at least 70 knots at minimum with a combat range of up to 217 miles and a total flight time of 30 minutes, with the hope of ultimately getting up to 403 miles and an hour of total flight time.

GA-ASI said that Eaglet’s sizable and powerful sensors and payloads also contributed to the drone being categorized as ‘large.’ The company has specifically designed Eaglet to carry a diverse range of payloads so that it can support multiple Army missions as needed, though no particular examples of these payloads were provided at this time.

Along with Eaglet, the Army has also been experimenting with a smaller drone called the Area-I Agile-Launch Tactically Integrated Unmanned System (ALTIUS) 600. The service has already demonstrated the ability of the MQ-1C to launch the ALTIUS-600 while in flight and has even exemplified how the same could be done from an ultra-light tactical vehicle on the ground. ALTIUS-600 has been fired from other platforms including fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, too. Other solutions for the ALE requirements are under development as well.

Despite all of the work the Army is doing in this regard, the Navy, Marines, and Air Force could also potentially benefit from the Eaglet ALE concept. The latter two services already operate their own fleets of MQ-9 variants in different capacities, and the same survivability challenges facing the Army’s MQ-1Cs will affect their counterparts as the modern battlespace evolves, as well. Knowing this, Eaglet could be of interest to non-U.S. MQ-9 customers as well, like the UK, Italy, France, Spain, and the Netherlands, which all operate the MQ-9A.

As for the larger ALE initiative, what comes out of the program is likely to become essential components of other top-end Army aviation programs, like the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft, for instance. ALEs acting as stand-in jammers, capable of disrupting air defense systems near the source of their emission will likely be critical to survival in future fights. The same capability could drastically help the survivability of MQ-1Cs and MQ-9s in medium-threat environments. This is in addition to expanded reconnaissance, kinetic, decoy, and even networking capabilities that ALEs are hoped to one day provide.

Now that Eaglet’s first flight has been completed, GA-ASI says that it is aiming to include the drone in other military exercises to “determine its potential.” If everything goes well and Eaglet performs as desired, the drone looks set to become another new capability for the Gray Eagle and the Reaper.

Contact the author: emma@thewarzone.com