The U.S. Air Force has been quietly in the process of trying to lease a small number of KAI T-50 Golden Eagle advanced jet trainer aircraft as it waits for the arrival of the first of its new T-7A Red Hawks. If the deal, which appears stalled for the moment, goes ahead, the aircraft could support a proof of concept experiment that could lead to ambitious and radical changes in how the service trains fighter pilots.

Aviation Week

published an update on Air Combat Command’s (ACC) little known RFX program on Mar. 18, 2020. ACC had announced it planned to enter into a sole-source contract with Texas-based Hillwood Aviation to rent between four and eight T-50s, with the expectation that the fleet, as a whole, would fly approximately 4,500 flight hours across 3,000 sorties each year for just one day shy of five years, in January. Hillwood, a subsidiary of The Perot Group, has a deal with KAI in South Korea to represent the T-50 in the United States.

It’s something of a curious development from the start, given that Lockheed Martin had partnered with KAI to pitch a variant of the T-50 for the Air Force’s T-X contract. Boeing, together with Saab, won that competition in 2018 with what became the T-7A Red Hawk. Lockheed Martin still lists the T-50A as an offering for “Advanced Pilot Training” on its website.

ACC wants the T-50s in the meantime to help begin testing a completely new training concept, also known as Project Reforge. U.S. Air Force General Mike Holmes, who is currently head of ACC, publicly outlined the plan in a piece for War On The Rocks in January 2019.

“The way the Air Force trains aviators has its roots in the training architecture that was built to churn out aviators in World War II,” Holmes wrote. “Pilot training in the 1930s lasted 12 months – and, despite the proliferation of GPS, glass cockpits, autopilots, and digitally aided flight controls – it still lasts 12 months today.”

At its most basic, the present system involves a three-phase Undergraduate Flying Training (UFT) process, the first phase of which is on the ground entirely. The second phase sees trainees get into the air in T-6A Texan II turboprop trainers. During the third phase, also known as lead-in flight training (LIFT), the future aviators move on to more representative aircraft types depending on their assignments. Those destined to become fighter pilots presently spend more time in the T-6A before moving on to the T-38 Talon jet trainer. The T-7A is slated to eventually replace the T-38.

Those future fighter jockeys then move on to the Introduction to Fighter Fundamentals (IFF) course. After that, it’s on to a Formal Training Unit (FTU) to learn how to fly a specific combat aircraft, such as the F-15C/D Eagle or F-16C/D Viper.

The current process imposes major hardships on future aviators. At present, a trainee pilot, and their family if they have one, has to completely move from one base to another three times in a span of fewer than two years.

On Mar. 3, the Air Force admitted it was short 2,100 pilots. This was an acknowledgment that a long-standing shortage of aviators was still ongoing, and had actually gotten slightly worse, despite cautious optimism last year that the trend was finally going in reverse. Speeding up and otherwise doing away with hurdles to training new pilots could certainly help turn this situation around.

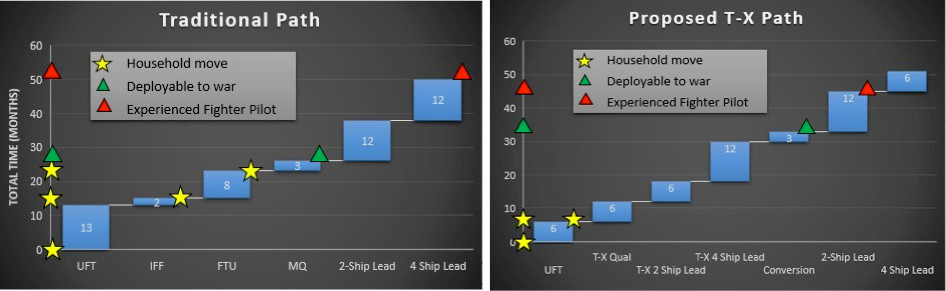

General Holmes’ plan envisions having future fighter pilots move only once, after completing the first two phases of UFT, to the home of their future operational fighter squadron. They would learn to fly the T-7A with a training unit there and then transition to flying their assigned combat aircraft at the same location. This would eliminate the need to send those individuals to another base for IFF and then to an FTU at yet another location before sending them on to an actual operational squadron.

In principle, this would significantly simplify the training pipeline and reduce hardships for future aviators. In turn, this would hopefully speed up the entire process and make it more attractive to new recruits. This would also allow them to forge valuable bonds and get experience working together with the same people they’ll eventually flying into combat with. Right now, there’s no guarantee that aviators leaving an FTU will go to the same operational squadron.

Having training units with T-7As at the same bases with operational fighter squadrons might also help ease other training demands. The T-7As could potentially serve as “red air” aggressors for routine training, something the War Zone has discussed in more detail in the past. Many combat units have to use their own aircraft in this role, which is an increasingly costly proposition, especially when it comes to high per-flight-hour costs to operate advanced stealth aircraft, such as the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. This also increases normal wear and tear on the airframes and puts precious flight hours on high-end combat aircraft.

The Air Force has now hired seven different contractors to provide red air support at bases across the country to reduce these operational and logistical strains. Still, having T-7As permanently stationed at the same bases as operational fighter units that could be used for adversary missions, in addition to their training duties, would only offer additional resources in this regard. ACC has also discussed the possibility of employing an even more fighter jet representative derivative of the Red Hawk, referred to presently as the “F/T-7X.” The War Zone

has previously noted that the Boeing-Saab design is already very much a light fighter that could have wide-reaching applications beyond flight training.

Having T-7A trainers collocated with operational fighter units could also simply be a way to save airframe life on the combat jets, in general, something the Air Force has already proven out on a more limited scale. Units flying the B-2A Spirit stealth bomber and U-2S Dragon Lady spy plane have T-38s associated with them to help pilots maintain basic flight proficiency and build flight hours without needing to fly either of these aircraft, which are extremely expensive to operate and limited in number.

The problem is that the Air Force isn’t scheduled to take delivery of the first T-7As, which offer advanced capabilities over the T-38 that Holmes sees as essential to putting his plan into action, until 2023. The service doesn’t expect to reach initial operational capability with the type until 2024. So, ACC needs to rent or otherwise acquire an interim type to begin experimenting with and refining Project Reforge now. This is where the T-50s would come in.

Seeing how well Project Reforge works, and what changes can be made to further streamline it, before the T-7As arrive makes good sense. So, it’s unclear why the Air Force has yet to formally execute the deal with Hillwood for the T-50s. Aviation Week said that the company declined to comment on the project.

The deal has already faced some hurdles since ACC first issued the RFX request for information, apparently without much public attention, in May 2019. Mission Support Systems (MSS), another Texas-based aviation firm, had competed with Hillwood for the deal. However, the company told Aviation Week that it only heard about the RFX solicitation after seeing it mentioned in an unrelated presentation regarding a separate Air Education and Training Command (AETC) effort to acquire a small number of advanced jet trainers itself to supplement its T-38 Talons. The aging T-38 fleet has suffered a number of major accidents in recent years and is becoming increasingly more difficult to maintain.

MSS had proposed leasing Italian-made Leonardo M-346 jet trainers to meet the RFX requirements. Leonardo had also competed in the T-X program, first together with Raytheon and then through its own U.S.-based subsidiary, with a variant of the M-346, known as the T-100.

The initial RFX plan included a requirement for supersonic speed, a capability the T-50 has, but which many other advanced jet trainers presently on the market, including the M-346 lack. The Air Force eliminated that requirement, which allowed MSS to compete, but then added a new demand that any jet it selected had to be capable of accepting a radar.

There is no production version or established conversion of the standard M-346 with a radar, at present. These aircraft have an Embedded Tactical Training System (ETTS) the emulates the capabilities of various systems, including radars, as a cost-saving measure. Having a fully-functional radar, as well as other systems commonly found on actual fighter jets, is not a necessity for even advanced jet pilot training. The T-7As will also use an ETTS. The M-346FA light fighter derivative does have a radar, but the installation is not backward compatible with basic M-346 aircraft.

KAI’s T-50 has always had a radar installed. The original T-50s for South Korea’s Air Force had Lockheed Martin AN/APG-67(V)4 mechanically-scanned pulse doppler radars. Newer, armed South Korean TA-50s feature the Israeli-made Elta EL/M-2032 radar. KAI also offers a light fighter jet version of the aircraft, the FA-50, with the EL/M-2032 as a radar option.

MSS told Aviation Week that the Air Force had devised the radar requirement in order to justify eliminating their bid and awarding a sole-source contract to Hillwood. The company had proposed integrating a Leonardo Grifo-series pulse doppler radar onto its M-346s within 12 months of getting a contract award, which ACC apparently rejected.

“The T-50 provides the advanced displays, training systems and active radar needed for the RFX. The M-346 variant provides advanced displays and training systems needed for the RFX but does not have an active radar at this time, and the timeline for incorporating one was unknown,” ACC said in a statement to Aviation Week. “Therefore, only the T-50 meets the basic requirements for the RFX.”

It’s not clear if MSS is protesting the sole-source RFX deal with Hillwood, which might explain, in part, why ACC has not moved forward to finalize it. Other factors could also be at play, not least of which being the increasingly widespread impacts of the COVID-19 novel coronavirus pandemic.

Project Reforge, as it is described now, is also extremely ambitious and it’s unclear if it is truly feasible, at all. This might prompt ACC to push it off amid various issues, including the COVID-19 crisis and Air Force’s broadly plans to trim its budgets.

Despite General Holmes very real criticisms of the present centralized system, it does limit the total number of advanced jet training units the Air Force has to maintain at any given time. Project Reforge would significantly expand the total number of airframes that the service’s maintenance and logistical chains would have to support at each of its operational fighter jet bases. Keeping all of these new miniature school houses running could create its own strains on Air Force resources, which might outweigh the benefits, depending on the exact number of T-7As that Holmes expects to have at each base.

ACC could ultimately decide to retain more of the existing training pipeline and implement the Project Reforge concept further along in the process. A new round of Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) decisions might also help by consolidating more fighter jet units at fewer locations.

Whatever aircraft ACC does or doesn’t acquire for Project Reforge in the end, the concept could certainly revolutionize how the Air Force trains its fighter pilots. With the shortage of aviators still causing serious headaches for the service, hopefully, it will be able to start experimenting to see if plan is truly game-changing sooner rather than later.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com