In the past week or so, there has been an unprecedented surge of domestic aerial activity from the U.S. military and law enforcement agencies in response to protests and rioting following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This has ranged from helicopters flying very low-level shows-of-force flights over parts of Washington, D.C. to drones and manned surveillance aircraft orbiting over numerous American cities to cargo aircraft bringing large numbers of troops to Andrews Air Force Base right outside the nation’s capital.

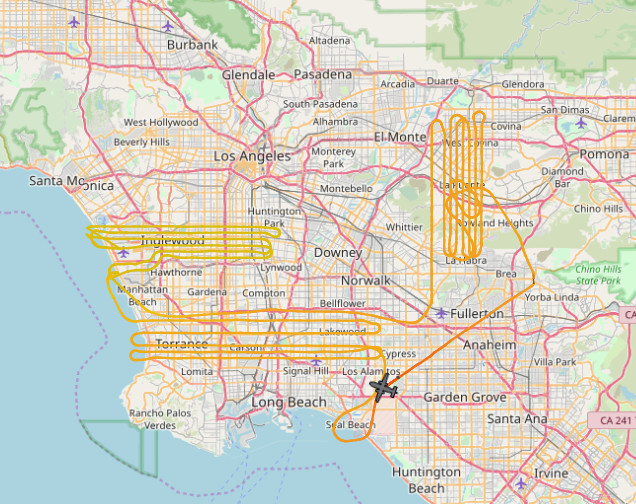

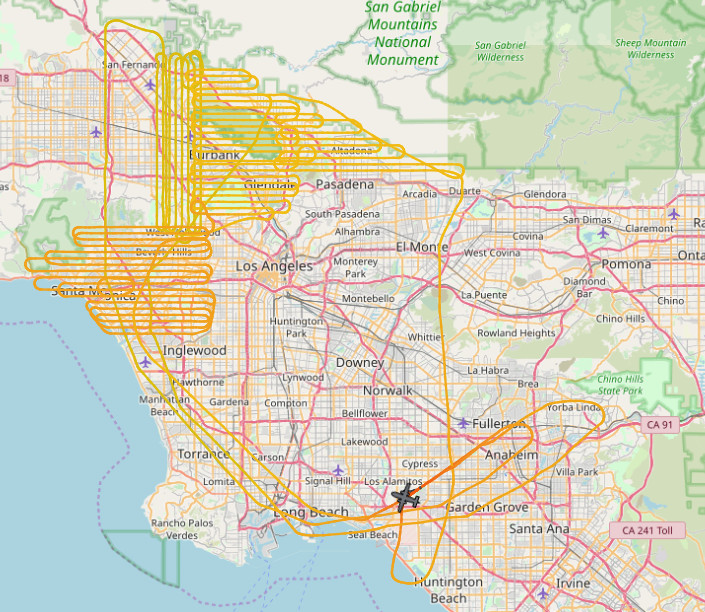

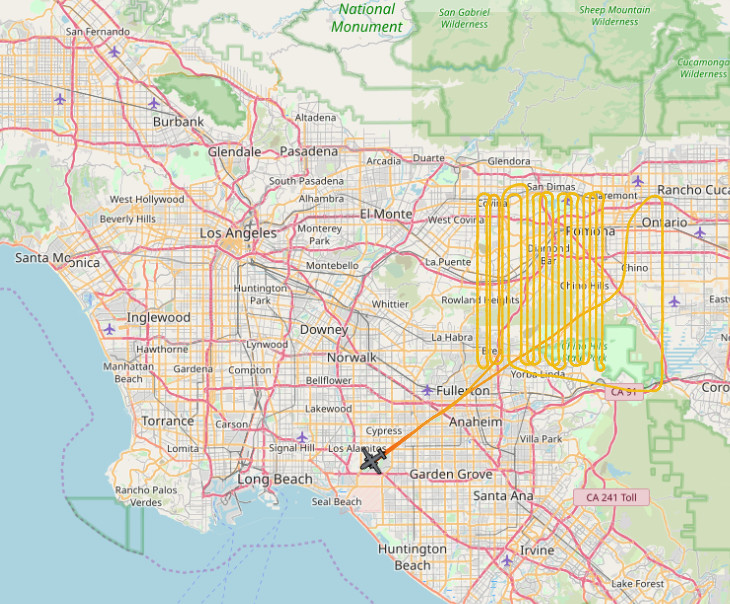

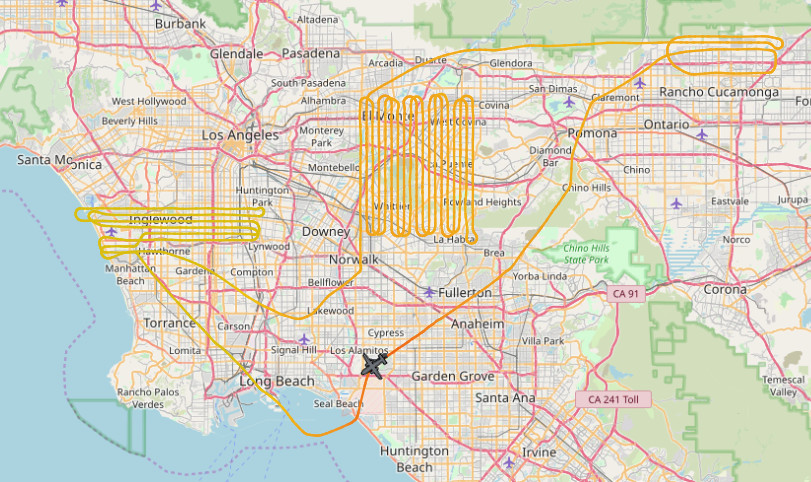

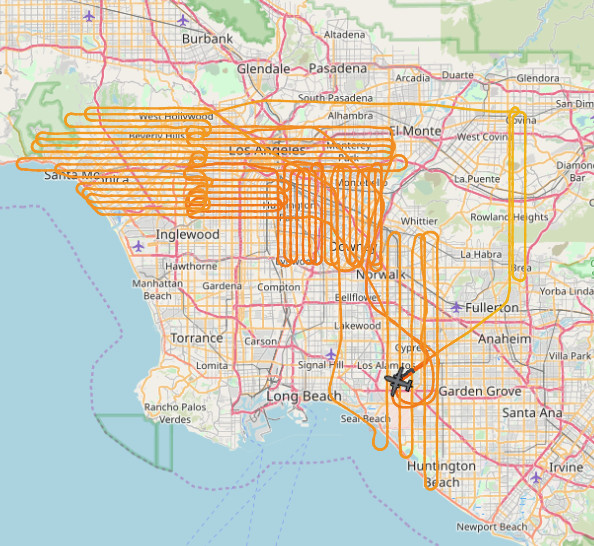

Increasingly more accessible online flight tracking software has made it easier to observe what military and police aircraft and helicopters are doing, but, especially now, it is not always easy to separate them from more mundane and routine flights that might appear unusual to the untrained eye. A good example of this is a series of missions that one Beechcraft King Air A90, with the civil registration number N67K, flew over the greater Los Angeles area between May 28 and June 1, 2020.

Each one of these flights, which are seen below, involved the plane flying long, regular tracks over certain areas Los Angeles and other nearby cities. To some, it looked like the plane might be flying a surveillance mission. Los Angeles has seen significant protests and rioting, as well as harsh responses from police, in reaction to the killing of George Floyd.

N67K is registered to an aviation services contractor called Dynamic Aviation, which has a long history of flying aircraft configured for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions on behalf of the U.S. military in conflict zones around the world, as well. The company’s fleets that are available for those missions include dark grey-painted King Air A90s.

However, this particular A90, which is part of a fleet of aircraft that are painted white and have red and blue cheat lines on the fuselage, engine cowlings, and tail, as well as red-tipped wings and tails, is configured for an entirely different type of mission, one that involves dropping loads of sterile flies. The California state government has a contract with Dynamic to provide this service as a means of controlling the population of Mediterranean fruit flies, or Medflies.

Medflies are native to sub-Saharan Africa, but have spread to California, among other U.S. states, via international trade and travel. These small insects are notably destructive to fruit and vegetable crops, making them a particular concern for the Golden State, which is the largest agricultural producer in the United States and an important source of food for the entire country.

In the 1980s, the California state government used helicopters to spray a pesticide called malathion to help control medflies, as well as mosquitos and other pests. A public outcry over potential cancer risks associated with malathion, combined with concerns from residents that the chemical would ruin the finish on their cars, led authorities to end the practice. The state subsequently shifted to the so-called Sterile Insect Technique, or SIT.

SIT involves aircraft releasing male insects, which are bred in captivity and then irradiated, making it impossible for them to reproduce, over an affected area. Females then make futile attempts to mate with them. The relatively short life span of most insects means there is then a good chance that they will die before finding a fertile mate.

This technique has been in use around the world since the 1950s to combat various types of invasive and disease-spreading insects. It has a long track record of success in controlling, as well as outright eradicating certain species in areas where it has been employed. Dynamic Aviation says it has been conducting SIT flights itself for more than 25 years, including as part of its long-standing contract with the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA).

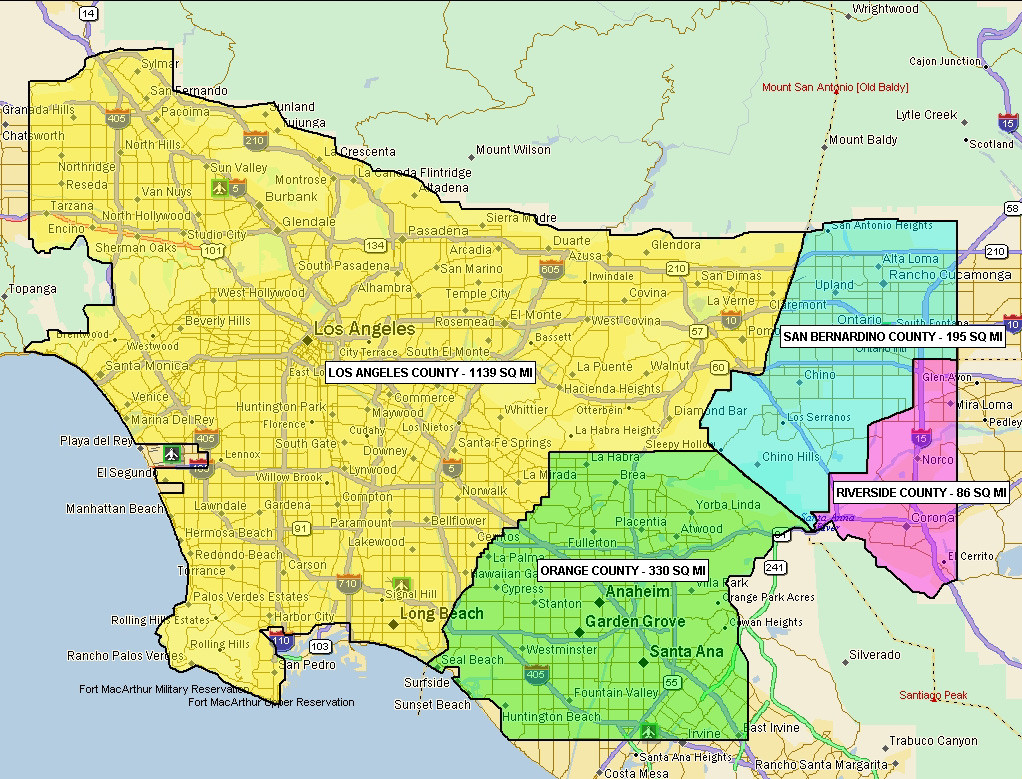

California’s Medfly Preventative Release Program (PRP), including Dynamic’s specially configured A90s, is run out of Joint Forces Training Base – Los Alamitos (JFTB-Los Alamitos), a California National Guard base in Los Alamitos, California, which is situated just to the southwest of Los Angeles. CDFA manages the program in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The state imports sterile Medflies in their pupae stage from a production laboratory that the CDFA runs in Hawaii and another one that USDA supports in Guatemala. The pupae arrive in bags mixed with fluorescent pink or orange dye, which then transfers to the flies as they grow. This allows CDFA and USDA personnel to identify the flies and track their spread. The bags also have radiation tags to indicate they have received a sufficient dose to render the flies sterile.

The flies are then bred in a controlled environment until they have “reached peak sexual maturity,” according to the CDFA website. Then they are chilled and packaged for delivery to Dynamic’s crews. Flies can survive at low temperatures in a state of hibernation, making them infinitely easier to transport.

At JFTB-Los Alamitos, personnel then load the flies into hoppers inside the A90s. The aircraft then dispense them over the designated are through chutes that stick out from the bottom of the fuselage. In addition to the special dispensing equipment, these aircraft have an additional navigation system, originally designed for crop dusters, which helps them fly those long, straight routes back and forth over Los Angeles and other communities in the area. They also have cameras underneath the fuselage to confirm that the insects are actually falling from the chutes.

A 2009 blog post by Ron Rapp, who worked for Dynamic and flew SIT-configured A90s over southern California, offers a highly detailed breakdown of how these missions go, from start to finish. The piece, which is worth reading in full, notably describes the unique challenges, as well as boredom, that the crews have to contend with, with Rapp writing:

“We are required to keep the aircraft within 150′ of the course line, 100’ of the desired altitude, and maintain 140 knots indicated airspeed +0/-5 knots. That’s not hard to do… for a while. But try doing it when you’ve been in the air for seven hours already. Fatigue? Yeah, it gets tiring.”

…

“Keep in mind most of our operations take place in the Los Angeles basin, the most highly congested airspace in the world. We operate close to terrain, at low altitudes under the LAX [Los Angeles International Airport] localizer, and in all sorts of odd places you don’t normally find airplanes. We need to do that to ensure a proper coverage of medflies. I believe we drop them at the rate of something like 32,500 flies per linear mile.”

“The system works well, but it does require a high level of vigilance from the pilots. The Los Angeles airspace was not designed to accommodate our kind of flying, but what we do is important enough that the controllers have maps of our regions and we have an excellent working relationship with them, often operating in Bravo airspace where other aircraft would not be allowed entry.”

“When we reach the end of a line (or ‘pass’, as we call it), we reverse course and fly the next line according to the data provided by the CDFA. Most of our regions are flown on north/south or east/west courses, but occasionally terrain will dictate an oddball course, such as out by Lake Elsinore.”

Beyond just the aerial application portion of the process, California’s Medfly control program is a major undertaking. The state takes delivery of more than 223 million pupae for processing every week, according to the CDFA website. The entire operation costs $16 million to run each year.

It is true that there are also drawbacks to SIT. The releases are species-specific, meaning that they can only work against one type of insect at a time, unlike pesticides. It can also be difficult to ensure the sterilized males go where they’re supposed to and there is an inherent risk that they might not have been sufficiently irradiated to actually prevent them from mating.

Still, the results, at least according to CDFA, appear to be worth that cost. Before it began the program, California saw an average of seven and a half major Medlfy infestations annually. The state now sees less than one every year, on average, thanks to the routine dispensing of the sterile flies.

So, while it might have looked like N67K was flying surveillance missions over Los Angeles in recent days, especially given the current context, it was actually doing its part to help control these pests and protect the state’s farming sector.

We want to thank @FatRomanticSlob for bringing N67K’s recent flights over Los Angeles to our attention.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com