Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro has said he will deploy elements of the country’s military to help fight an unprecedented spate of fires raging across the country’s portion of the Amazon rainforest, which have the potential to become a major global environmental disaster. The decision comes amid growing international criticism of how the Bolsonaro Administration had been handling the crisis, which is also impacting neighboring countries. This has notably prompted Bolivia to lease the world’s only 747 Supertanker, the world’s largest firefighting aircraft, which arrived in that country today to help combat the blazes.

Bolsonaro made the announcement on Aug. 23, 2019, a day after holding an emergency cabinet session, but offered little detail about what military forces might end up deployed to support the firefighting efforts at that time. Later in the day, he said the military would “act strongly” and deployments would begin on Aug. 24, 2019.

Since Jan. 1, 2019, there have been more than 75,000 recorded wildfires across Brazil, a more than 80 percent increase over last year. This is also more than the total number of blazes in 2016, when drought fueled a particularly bad fire season. Many of the fires currently raging in Brazil are in that country’s portion of the Amazon, which accounts for 60 percent of that Amazon Rainforest’s total area.

“The protection of the forest is our duty,” Bolsonaro said. “We are aware of that and will act to combat deforestation and criminal activities that put people at risk in the Amazon. We are a government of zero tolerance for crime, and in the environmental field it will not be different.”

Though Brazilian authorities have not said what military units might be headed to help battle the fires raging in the Amazon, the country does have a dedicated Military Firefighters Corps. This is a reserve component adjacent to the country’s Army, which has some 50,000 members spread across Brazil’s states. These units have specialized equipment and could receive orders to pool their resources to better respond to priority areas.

The country’s active Army might also deploy military engineering units, which are often well suited to performing certain firefighting tasks, such as creating firebreaks and otherwise clearing debris. Ground forces have access to tactical trucks and other vehicles that would be valuable to move personnel, equipment, and supplies into more remote areas. The Brazilian Navy and Marines Corps also have amphibious vehicles and riverine and landing craft that could perform similar functions in inland waterways, such as along the Amazon River and its tributaries.

Brazil’s Army, Navy, and Air Force, all have fleets of helicopters that could carry “bambi buckets” to conduct water bombing missions in remote or otherwise hard to reach areas, as well. Maybe its armed services’ most powerful firefighting weapon, the Brazilian Air Force has a limited number of Modular Aerial Firefighting Systems (MAFFS) that convert its C-130 Hercules airlifters into water bombers. You can read more about MAFFS in this past War Zone story.

“Whatever is within our power we will do,” Bolsonaro said on Aug. 23, 2019. “The problem is resources.”

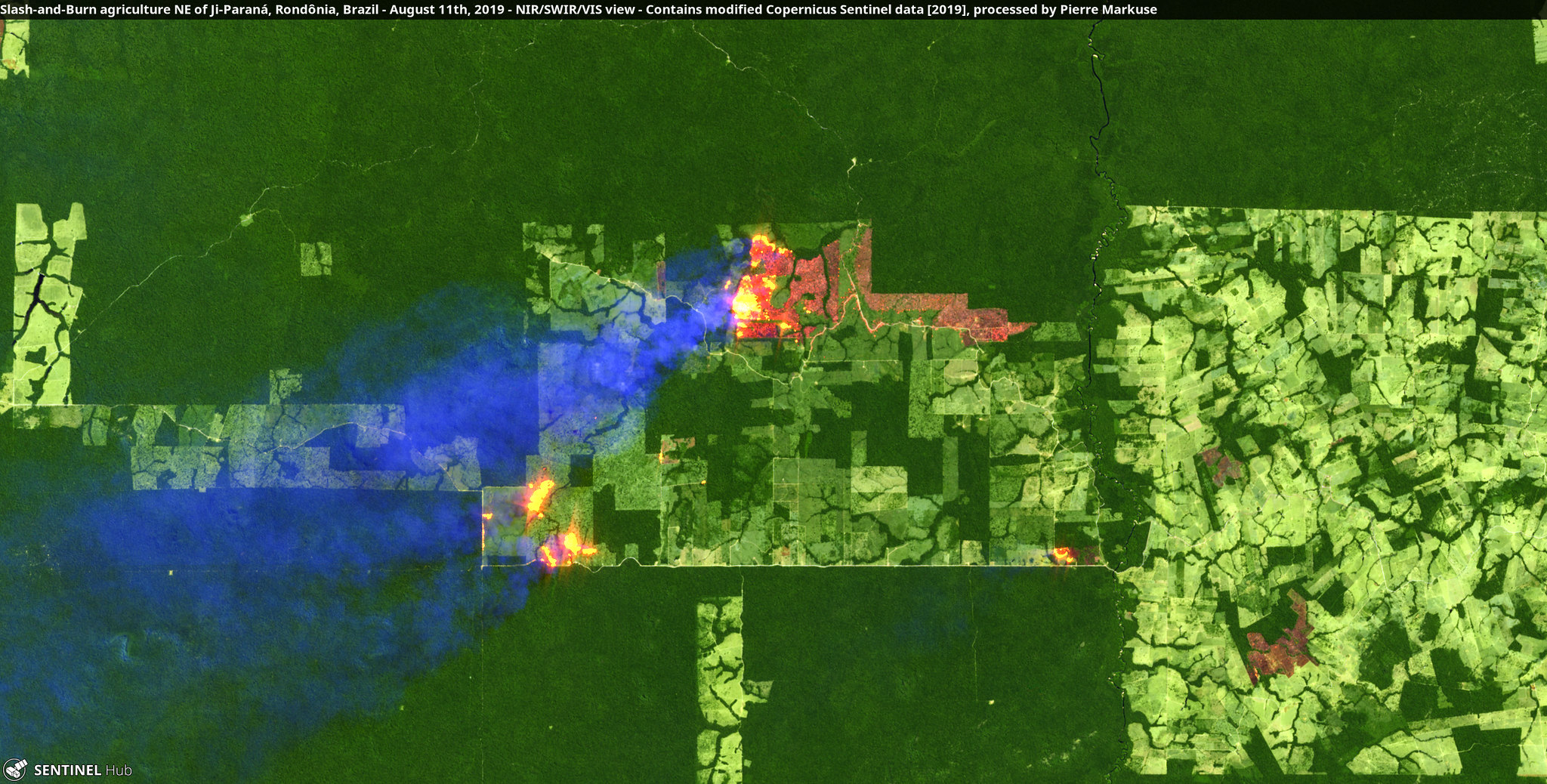

Unfortunately, as Bolsonaro noted, it remains to be seen whether Brazil can quickly put together the necessary resources to respond to the crisis, which is so extensive, some of the fires are readily visible from space. Brazil already lost 1,330 square miles of Amazon Rainforest – an area larger than the state of Rhode Island – to fires in the first six months of 2019, according to The New York Times.

“It’s impossible to be everywhere at the same time,” Coronel Demargli Farias, the chief of firefighters in Brazil’s Rondônia state, also said on Aug. 23, 2019. “Even if we had 50,000 men.”

Brazil could appeal to the international community to provide additional firefighters and support, but it might find that other countries are facing similar problems. The U.S. Air Force has its own C-130s equipped with the improved MAFFS II system, which you can read about more here, but would have to balance any requests for assistance against the potential demand domestically. The United States is in the middle of its own fire season. On Aug. 23, 2019, U.S. President Donald Trump did say that “we stand ready to assist” in a Tweet that was otherwise supportive of Bolsonaro.

This year has been especially bad for fires across Europe and into Asia, with Russia, in particular, finding its own resources stretched thin. This has also put high demand on commercial aerial firefighting companies, who may not have assets available to take Brazilian contracts.

Case in point, a day before Bolsonaro announced his intention to deploy the military to help battle the fires, Bolivian President Evo Morales announced he had leased the 747 Supertanker Very Large Aerial Tanker (VLAT) aircraft from Global SuperTanker Services in the United States. Bolivia, which is significantly smaller than Brazil, is in the midst of its own fire-related crisis, having lost forests across an area roughly the size of the state of Delaware to blazes so far.

“We believe that with this plane, we can put out the fire,” Bolivian Defense Minister Javier Zavaleta said on Aug. 22, 2019. Again, the aircraft, which landed in Bolivia today and can carry an impressive 18,600 gallons of fire retardant chemicals or water on each run, will certainly help, but it cannot fly missions everywhere at once. Also, these huge tanker aircraft are especially well suited for containing fires, not putting out large ones that are already burning.

Aerial water bombing, as well as other direct firefighting activities, also require significant additional support capabilities to be truly effective. Expert command and control, intelligence gathering, and spotters in the air and on the ground are all necessary components that Brazil will have to either provide itself or try to source from elsewhere.

At the same time, Bolsonaro, who has steadfastly described the fires as a purely internal matter, may also find asking for help to be politically fraught as he has received significant criticism, coupled with threats of economic action, over his response, or lack thereof. The hardline rightwing President has gone so far as to blame environmental groups for starting the fires deliberately to smear him, a claim he has provided no evidence to support. The Brazilian President is on record decrying environmental restrictions on developing the Amazon were impediments to economic growth in many of the country’s industries, including farming, logging, and mining.

Humans do seem to be responsible for the bulk of Brazil’s current fires, through accidents and deliberate action. Environmental activists have cited Bolsonaro’s policies as emboldening ranchers, in particular, to extend their efforts to slash and burn the rainforest to clear more grazing land, which has been a source of many of the fires.

Bolsonaro had previously dubbed himself “Captain Chainsaw,” though he says that was in response to what he claimed were inaccurate deforestation figures. The Brazilian President also fired the director of the National Institute of Space Research after they released satellite imagery and accompanying data proving there had been a noted rise in slashing and burning earlier in the year.

“Our house is burning. Literally,” French President Emmanual Macron wrote on Twitter on Aug. 22, 2019. “The Amazon rain forest – the lungs which produces 20% of the planet’s oxygen – is on fire.”

The French government has been a particularly notable critic of Bolsonaro’s and has now withdrawn support from a European Union trade deal with the South American economic bloc Mercosur, of which Brazil is a part. Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar has since warned that his country could follow France if Brazilian authorities did not take greater action. Germany and Norway are also withholding financial support for the Amazon Fund, which supports preservation initiatives with regards to the rainforest.

If Bolsonaro does finally ask for help, it may be impossible for the international community to ignore the crisis, though. As Macron noted, the Amazon as a whole helps process a significant amount of the carbon dioxide produced in the world, generating oxygen in return. Loss of significant parts of the rainforest could also have major enduring negative impacts on animal and plantlife biodiversity.

“There are large negative consequences for climate change globally, as the fires contribute to carbon emissions,” Robin Chazdon, a University of Connecticut professor emerita who worked on tropical forest ecology, told NBC News. If Amazon is “not allowed to regenerate or be reforested, they will not be able to recover their high potential for carbon storage.”

“These massive fires burning now reduce the resilience of the Amazon forest to future droughts and climate change at the same time that this forest is needed to mitigate against these threats,” Chazdon added. “Protection and restoration of the Amazon forest has never been more urgent.”

“If we kill enough forest, we may be tipping the Amazon into a new, much drier state, and it may turn into a savanna,” Roel Brienen, who is presently a professor at the University of Leeds in England and has spent over 15 years studying the Amazon basin, also told NBC News. “This would be a great loss to our planet and almost means game over for our battle against climate change.”

Sending in Brazilian military units could certainly give a much need boost to the firefighting efforts, but it remains to be seen how much of an impact they will have and how long it will take them to make their presence fully felt. Whether or not Bolsonaro likes it, the crisis already appears to have global ramifications and the international community should be ready to step up to help avoid an even greater catastrophe given how limited the Brazilian response has been so far.

Editor’s note: It’s always a good time to help out! Donating a few dollars to the groups like Global Wildlife Conservation, Rainforest Action Network, and the Rainforest Trust can help preserve and protect the awesome wilderness and the animals that call it home in the Amazon and other locales around the globe.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com