During the Cold War, the Soviet Union considered building a fleet of missile-armed Lun-class wing-in-ground-effect vehicles, also known as an “ekranoplans.” Now, Russia says it has plans to revive this concept with a design tentatively known as “Orlan,” which could potentially offer the country a novel access and anti-access weapon in the increasingly contested Arctic region, as well as in more constrained waterways, such as the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

On July 30, 2018, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov announced that a combat-capable sea-skimming vehicle would be part of the State Armament Program for 2018-2027. Since at least 2015, there have been reports that the Kremlin has been considering bringing back wing-in-ground-effect (WIG) designs, but primarily for transport and search and rescue duties.

“The [Orlan] prototype will be created as part of this armament program and it will carry missile armament,” Borisov said, according to Russian state outlet TASS. The deputy prime minister said that the vehicle would be able to help patrol Russia’s vast littoral regions, especially its maritime border along the Arctic and its claims in that region.

WIG designs are essentially a seaplane that flies very close to the surface of the water. In principle, the concept allows for an efficient, high-speed “water” craft that doesn’t suffer from the drag of actually sailing on the surface and from having a wing that can generate more significant lift. The Soviets, and others who have experimented with these types of vehicles, looked into variants that could combine the ekranoplan’s benefits with the ability to fly at higher altitudes.

Borisov did not offer any other specific details about the new Orlan and it’s not clear if this design will be in any way related to the Soviets’ Project 904 or “Orlyonok,” which means “eaglet” in Russian. NATO had dubbed this craft, which has a maximum take-off weight of approximately 125 tons, as the “Orlan-class.” Of the five known examples, Russia scrapped two of them and turned the other three into non-functional monuments.

Still, in terms of its basic shape and performance, the established Orlyonok design might provide a good starting place for a new ekranoplan missile craft. It has a good payload capacity due to its original role as a transport and reportedly boasted a cruising speed of nearly 250 miles per hour over a range of more than 900 miles. The original type had a turret on top with a pair of 12.7mm machine guns and a simple navigational radar.

In order to arm the craft, Russian engineers could conceivably look to the larger Lun-class design and mount missile launchers on its upper spine of the fuselage on the existing Orlyonok. The only Lun that the Soviets ever built, also known as MD-160, could carry six P-80 Zubr anti-ship cruise missiles, which NATO called the SS-N-22 Sunburn, in this configuration.

However, the existing Project 904 design features a large Kuznetsov NK-12MK turboprop engine, the same type found on Russia’s Tu-95 Bear bombers, at the top of the tail and firing missiles from the top of the craft might have some impact its function and, in turn, the ekranoplan’s performance. The Orlan-class also had a pair of jet engines in the nose to propel the craft.

The Lun-class did not have a tail-mounted engine of any kind, using that space instead for a Puluchas search radar and other equipment. It’s hard to see where else missiles might easily go on the existing Orlyonok design, though engineers could potentially put them on top of its wings in water-tight canisters.

At the same time, it could be possible to position the launchers far enough forward for them not to have any negative effects on the NK-12. Similarly, a missile system semi-recessed in the fuselage that fires the weapons off to the sides instead could avoid the issue altogether. The missiles Russia installs on the ekranoplan might be small enough for it not to matter one way or another. Compared to the P-80, more recent Russian anti-ship missiles have become light and compact enough to make using a smaller ekranoplan such as the Orlyonok feasible as a launch platform in the first place.

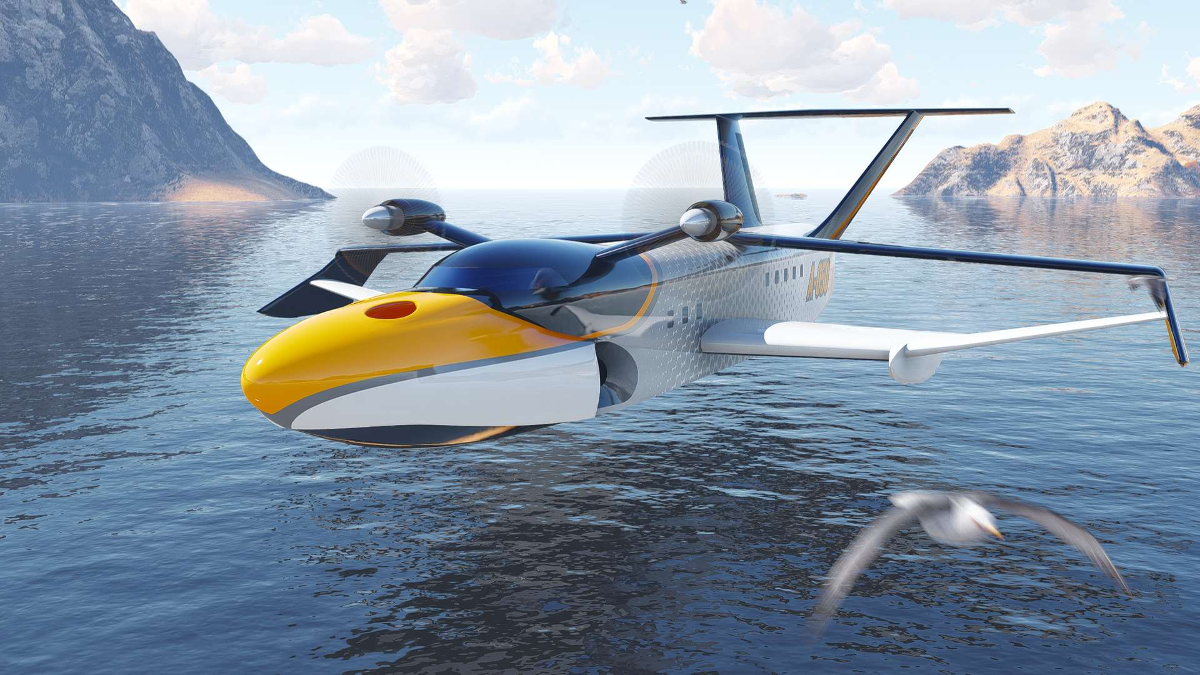

There are other designs that would fit Deputy Prime Minister Borisov’s basic description for the new Orlan, too. The 737-sized A-050 Chaika, or “Seagull,” is supposed to begin flight testing in 2022 and could serve as the basis for a missile-armed type. The firm responsible for this design, Alexeev’s Hydrofoil Design Bureau, has a number of other types that might work, as well.

Borisov did not specify any particular type or manufacturer and did not say specifically what kind of weapons the new Orlan might carry, either. He did note, however, that it would be used to fill in for more traditional defenses in the sparsely populated Arctic, according to TASS, but the most likely armament would be some type of anti-ship cruise missiles. The deputy prime minister also noted the craft’s potential value in the Black Sea and Caspian Sea and the Kremlin could also potentially deploy them to the highly strategic Baltic Sea.

In a maritime patrol role, an ekranoplan carrying a load of supersonic P-800 Oniks anti-ship cruise missiles could challenge the ability of potential opponents to move freely through a certain area or engage them rapidly during an actual skirmish. The high speed of the vehicles combined with that missile’s over-the-horizon range could allow the crew to quickly get into position on short notice or readily move to another area to respond to the changing nature of the threat.

Multiple missile-armed WIGs might be able to threaten enemy surface ships from multiple directions, as well, limiting their ability to make the most of their defensive capabilities. At the same time, Orlan’s low-altitude flight path and speed might make it harder to detect and engage, as well. Ekranoplans already have the benefit of being effectively impervious to torpedoes and naval mines.

The video below shows Russian land-based launchers firing P-800s during an exercise.

The ability to operate far from and independently of traditional naval and air bases would only make the vehicles more flexible operationally. This might give Russian ekranoplan units equal ability to gain access to certain areas and deny opponents the ability to operate in those spaces.

Depending on how common the missile-armed variant is to other proposed transport types, the combat-capable versions might be able to serve as escorts for the others into hostile territory. This could give Russia the ability to rapidly deploy forces on sea and land into specific areas during a conflict.

It would likely take relatively little effort to turn a defensive missile armed Orlan into an offensive weapon armed with land-attack cruise missiles, such as Kalibr, to actively threaten enemy shore-based defenses and sites further inland, especially in the close-quarters environment of the Baltic Sea or the Black Sea. Russia has also demonstrated that the P-800 has a limited land-attack capability itself, which could give the ekranoplans some multi-purpose functionality without necessarily needing to carry more than one type of weapon.

But, regardless, how viable a surface-skimming missile craft might actually be remains to be seen. Ekranoplans have historically proven to be complicated to operate and maintenance intensive in general, with the Project 904 types reportedly suffering from serious corrosion issues, according to a 1993 edition of Combat Fleets of the World. That year the then recently independent Russia decided to retire the remaining Orlyonoks from active service.

Beyond that, it’s also unclear how committed Russia is to this project or whether it might end up shelved in favor of other defense priorities. The county has continually pushed back projects to build larger traditional ships in order to free up funding for other, high-profile programs, including a host of nuclear-armed strategic weapons developments.

Still, with the existing experience with the Lun and Orlan-classes, together with modern improvements in engine and airframe technology, the Russians may see ekranoplans as a relatively low-risk and cost-effective investment. The country has already been spending a not insignificant amount of time and resources on systems specifically to support its Arctic operations, as well.

The Kremlin has said it wants to begin flight tests of cargo-carrying and search and rescue types by 2022 or 2023. The armed versions could easily follow afterward or go into development at the same time as a variant of those designs.

We will definitely be keeping our eyes open for the possible reappearance of missile-toting Russian ekranoplans in the Arctic or elsewhere.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com