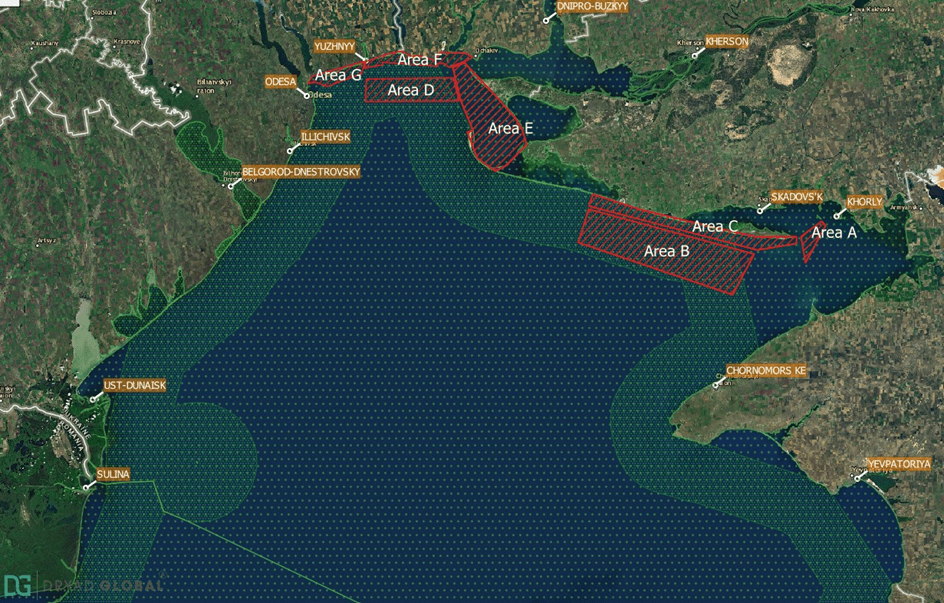

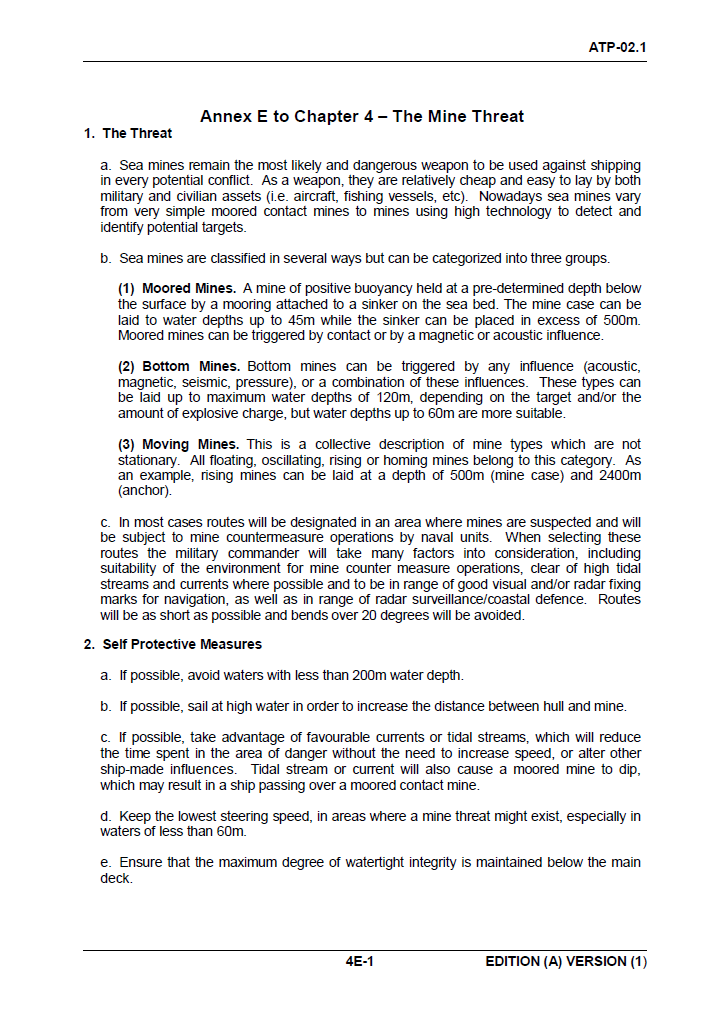

Many hundreds of mines floating in the Black Sea threaten any deal – no matter how unlikely – to allow the shipment of tens of millions of tons of Ukrainian grain.

With Ukraine unable to ship anything because of Russia’s naval blockade of its ports, Turkey and Russia are talking about a plan to provide safe passage for cargo ships.

But Ukraine and Russia are now arguing over the removal of sea mines that endanger any vessel traveling to those ports.

The whole matter, however, may be moot.

Ukraine officials claim it would take six months to clear the coast of mines, The Guardian reported Tuesday.

The paper reported that Markiyan Dmytrasevych, an adviser to Ukraine’s minister of agrarian policy and food, said Tuesday that regardless of any agreement, thousands of mines would remain floating around the port of Odesa, and elsewhere.

The reason, he said, was that it will take until the end of the year to clear out all the mines.

Even if a deal were hammered out, any demining effort would entail a massive undertaking, requiring specialized equipment to scour wide swaths of open water. And with both Russia and Ukraine accusing each other of planting the mines, the likelihood of cooperation during this bloody conflict is practically unthinkable.

The danger of mines, regardless of who put each of them there, is no theory in this region.

Sea mines have been found off both Turkey and Romania and in March, the Estonian cargo ship Helt sank after apparently striking a mine in the Black Sea. The concern is so great that on June 1, NATO put out a warning about the threat.

“Drifting mines have been detected and deactivated in the Western Black Sea by coastal nation’s authorities,” according to the warning. “The latest statement of regional authorities, confirming another sighting of a mine, shows the threat of drifting mines in the Southwest part of the Black Sea still exists.”

Another stray sea mine was detected and deactivated in the southwestern part of the Black Sea on April 6, NATO reported.

“National authorities stated that the searches for mine-like objects are ongoing. The threat of more drifting mines cannot be ruled out.”

As a result of these threats and others – several ships have been struck by explosives during this war – shipping insurance for ships heading to the region has skyrocketed.

“There is clearly a growing nervousness around the region in the insurance market, especially in relation to the Black Sea,” Marcus Baker at insurance broker and risk adviser Marsh told Reuters.

On March 7, the insurance industry’s Joint War Committee (JWC) issued an advisory that its high-risk area had been widened to waters close to Romania and Georgia because of the growing threat, Reuters reported.

The impasse comes as worries mount over global food shortages stemming from the war. According to the UN, Russia and Ukraine supply about 40% of the wheat consumed in Africa, where prices have already risen by about 23%, The Guardian reported.

Combined, the warring nations account for about 33 percent of the world’s grain supply, according to the Times of London, which reported that prior to the war. Ukraine had been expected to produce 80.5 million tons this year. Thanks to the resulting war-caused shortages, wheat prices have jumped by a third since Russia invaded on Feb. 24.

The imbroglio over the sea mines again raises the issue of the best way to ensure freedom of navigation in the Black Sea.

Ukraine President Volodomyr Zelensky told the Financial Times that while, in theory, he supports Turkey’s initiative, no Russian vessels should be allowed in any safe corridors.

“On UN-led talks to restore access to Ukrainian Black Sea ports, Zelensky was willing to back the idea of a maritime corridor to enable grain exports from Ukrainian ports as long as no access was given to Russian ships,” the paper reported. “There was no need for a dialogue with Moscow to resolve the blockade given that the only threat to world food supplies was coming from Russia, he said.”

Zelensky has also warned that 75 million tons of grain could be stuck in Ukraine by the autumn unless there is a clear break in Russia’s naval blockade of the Black Sea.

It makes no sense for Ukraine to allow Russia to offer any safety guarantees, Latvian Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš told the Atlantic Council Wednesday.

“Imagine you’re in Ukraine and Russia is going to guarantee the security of the sea route if you demine the port of Odesa,” he said. “in other words, you take away the defenses and that the power that will guarantee that everything is fine is the same power that’s trying to wipe you off the map. “That’s a no-go.”

One alternative, Kariņš raised, could be for a NATO nation to send a warship to Odesa.

“What should NATO’s role here be?” he asked, rhetorically. “This is a very serious question in terms of freedom of navigation. So why could not a U.S. or French warship go through the Bosphorus and dock in the port of Odesa?”

However, that too appears to be a no-go, at least in terms of any U.S. warships, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby has said.

Thanks in large part because of small, but significant difference between east and west European train track gauges, shipping Ukrainian grain west via train is a huge problem, he added, making the sea route even more important.

Rail cars “cannot move from Ukraine into Poland without changing the rail car chassis or the entire rail car,” Kariņš said. “And imagine thousands and thousands of grain cars having to pour from one to another. [It costs] incredible time and money.”

Some grain exports from Ukraine, he added, have taken nearly three weeks as a result, compared to about 36 hours under pre-war conditions.

There’s another factor making any deal for safe passage of grain through the Black Sea unlikely. Russian President Vladimir Putin has teased the concept of providing a safe corridor for ships carrying grain, but there’s a big catch. In return, he wants an easing of western economic sanctions. That’s something Ukraine’s allies have said is also a no-go.

If Wednesday’s back and forth between Ukraine and Russia is any indication, it could be a very long time before the world sees any grain from the region.

“Lavrov’s words are empty,” Ukraine Foreign Ministry spokesman Oleg Nikolenko tweeted Wednesday in response to statements by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov that Ukraine should demine or create safe corridors.

“Ukraine has made its position on the seaports clear,” Nikolenko Tweeted. “Military equipment is required to protect the coastline and a navy mission to patrol the export routes in the Black Sea. Russia cannot be allowed to use grain corridors to attack southern Ukraine.”

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com