During the Cold War, the air force of North Yemen — also termed the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) — was probably best known for flying Soviet-delivered MiG-17 and MiG-21 fighters. However, the country also operated Northrop’s F-5E Tiger II light fighter aircraft from 1979, a type that first flew just a few years earlier in 1972. How Yemen came to acquire its small fleet of American F-5Es is a truly wild story.

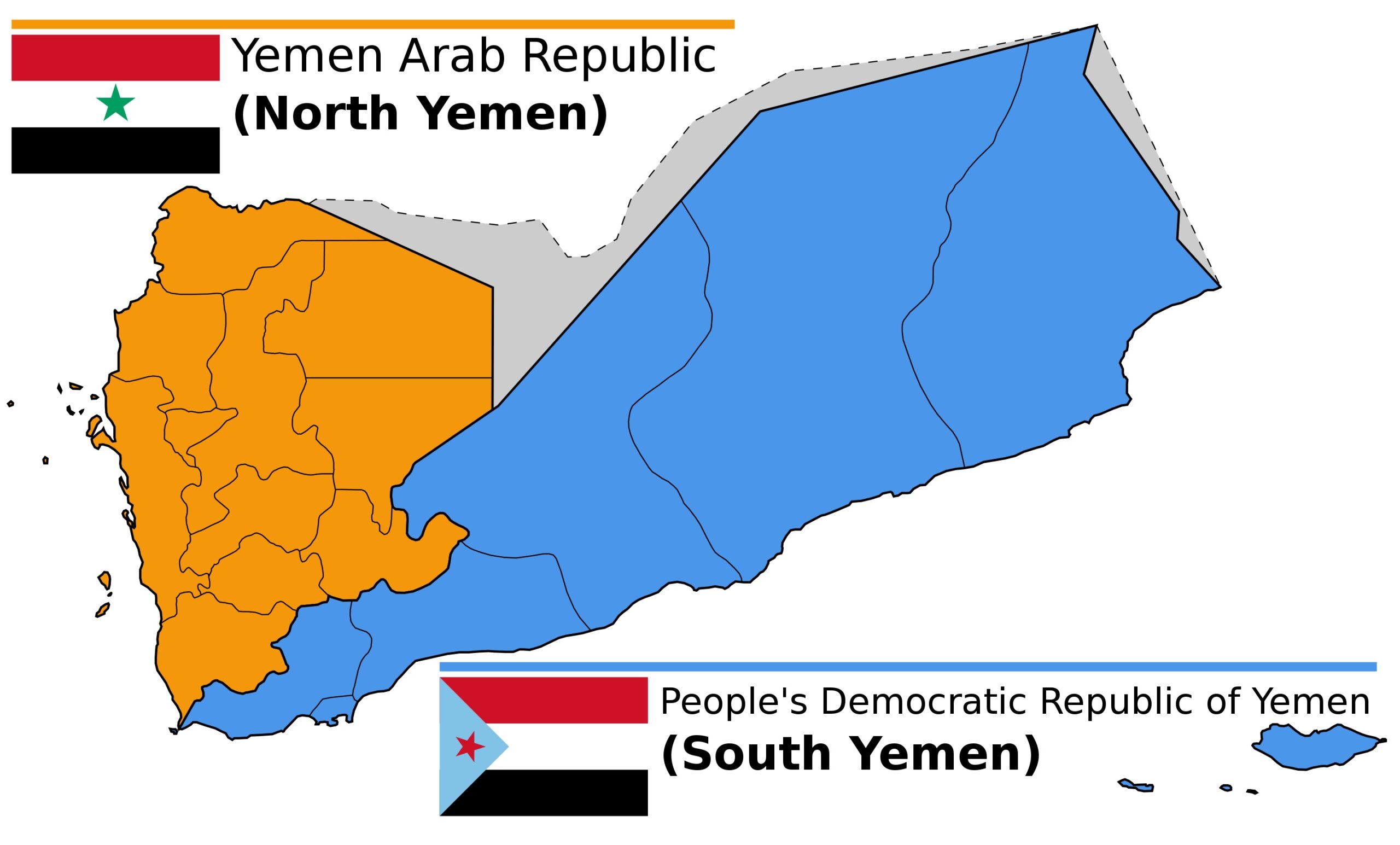

The country’s acquisition of said aircraft was intrinsically linked to the Second Yemenite War of March 1979. Historically, North Yemen was a part of the former Ottoman Empire during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, while South Yemen was officially part of the British Empire from the mid nineteenth century. Northern Yemen — or simply Yemen — was first recognized as a sovereign state by the U.S. in 1948, although its roots date back to 1918. The country was later recognized as the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) in 1962, while the People’s Democratic Republic of Southern Yemen (PDRY), a communist state with close ties to the former Soviet Union, was recognized in 1967. A bitter civil war was waged between the two from 1962-1970, which resulted in Northern victory.

The early 1970s was a period that saw significant unrest and political instability between the North and South, leading to the First Yemenite War of 1972. The conflict lasted just three weeks between September and October, with the countries vowing to unify as part of the Cairo Agreement. Stability did not last, however, with a second Yemenite War erupting in late February 1979.

Under President Jimmy Carter, the U.S. decided to aid the YAR by providing a range of military equipment in early March 1979, bankrolled by Saudi Arabia — Saudi Arabia had supplied military aid to the YAR during the first Yemenite War.

The $390 million worth of aid included 12 F-5E aircraft, eight of which were originally manufactured for Ethiopia but then embargoed, and four of which were new builds. The package also included two C-130 transport aircraft, 60 M60 tanks, 50 M113 armored personnel carriers, 302 AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, as well as howitzers, grenade launchers, and other ammunition. Additionally, Saudi Arabia was permitted by the Carter administration to send four of its two-seat F-5B Freedom Fighters to the YAR.

Carter’s decision to provide the YAR with military equipment was illustrative of the U.S.’s shifting policy towards the Middle East — a product of a complex geopolitical reality within the region. Of course, previous administrations had provided equipment to the YAR. In 1976, for example, the Ford administration provided the YAR with $140 million of U.S.-supplied equipment, which consisted primarily of ground force weapons and materiel including howitzers, surface-to-air missile systems, and trucks.

However, by 1979, despite considerable debate within the Carter administration over the U.S. military presence in the Persian Gulf, the U.S. began adopting a more active military presence in the region. In January of that year, 12 U.S. F-15s were sold to Saudi Arabia — primarily as a gesture of reassurance from the U.S. with regards to Saudi Arabian security, and to ease the impact of the upcoming Egyptian-Israeli peace deal, which was subsequently signed in March. Come February 1979, however, the Carter administration made it clear that such gestures were part of a major shift in U.S. policy in the region.

“We have made a policy decision about a more active role in the area,” the then Secretary of Defense Harold Brown said during a 10-day trip to the Gulf and the Middle East that month. “We have told those countries things that they have not heard for a long time — namely, that the United States is deeply interested in the Middle East, we are worried about what the Soviets are doing, we intend to be involved.” During Brown’s trip, which was principally focused on the negotiation of arms transfers, the Secretary of Defense ended up promising Saudi Arabia that the U.S. would furnish the YAR with M60s and F-5s, if the Saudis footed the bill.

Before Brown’s pledge could be brought before Congress, the PDRY launched an invasion of the YAR on February 28, 1979, spearheaded by PDRY Air Force MiG-21s and Su-22s. With pressure rising, the Carter administration increasingly began to view the situation in Yemen as a serious threat to U.S. interests in the region, fueled by Soviet-backed aggression. On March 7, 1979, Carter assessed that the fighting constituted an emergency that threatened U.S. national security and necessitated the application of Section 36(b) of the 1976 Arms Export Control Act for the very first time. The use of said clause allows the president to bypass obtaining Congressional approval on exporting arms when U.S. national security is threatened. As such, the $390 million worth of aid for the YAR, including the 12 F-5Es, was fast-tracked.

When the first F-5Es arrived, six weeks ahead of schedule, the North Yemeni Air Force did not have the pilots nor the resources to operate them. This accelerated delivery led to a scramble by the Saudis to recruit foreign pilots to train the YAR’s pilots on the F-5E. Eventually, an agreement was brokered by the U.S. and Saudi Arabia with Taiwan to send a number of Taiwanese pilots to operate and maintain North Yemen’s F-5Es. The Republic of China Air Force (ROCAF) had several years of experience working with the F-5E specifically, which it had first received in May 1975, while its first F-5s from the U.S. were delivered in 1965.

Despite these efforts to quickly furnish the YAR with F-5Es, the Second Yemenite War ended swiftly on March 19, 1979. In total, the conflict lasted three weeks and two days. However, the presence of Taiwanese personnel in North Yemen was long-lasting. Initially, 80 personnel — including pilots and ground crew members — were sent from Taiwan to Sana’a in order to operate and maintain the F-5Es, led by Lt. Col. Che Meng-sian. By the end of 1979, 16 F-5s arrived at Dailami Air Base, Sana’a.

The Taiwanese pilots integrated with the 112th Squadron of the Yemen Arab Republic Air Force (YARAF), which was also known as the “Desert Squadron.” As Tom Cooper points out in his book, Hot Skies Over Yemen: Aerial Warfare Over the Southern Arabian Peninsula: Volume 1 – 1962-1994, the ROCAF Task Force stationed in North Yemen was subordinate to Taiwan’s military liaison office in Saudi Arabia. The head of the ROC Military Liasion Office in Saudi Arabia, usually a full colonel, oversaw the work of the task force headquartered at Dailami Air Base.

Until 1985, Taiwanese pilots and ground crew constituted the majority of the 112th Squadron, at which time enough YAR pilots were trained on the F-5E to start to take over. However, novice YAR pilots, who had minimal training opportunities, struggled to adapt to the F-5Es and other new equipment, including Soviet-delivered MiG-21s. By the end of 1985, the YARAF lost 25 aircraft in various accidents, including four MiG-21s and a brand new F-5E, which ended up crashing when a Saudi pilot was flying it to Saudi Arabia for light repairs.

Taiwan’s pilots stayed in the country for several years after 1985. Recently declassified documents indicate that over 1,000 Taiwanese pilots and ground crew were deployed to the YAR from 1979-1990 as part of what was known as the Great Desert Program.

In 1990, the two Yemens united to become the Republic of Yemen.

As for the fate of the country’s F-5s, the aircraft saw action in 1994 when civil war briefly ignited between the north and south from May to July. In early May, Maj. Nabi Ali Ahmad downed at least one Southern MiG-21 while flying an F-5E, deploying AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles. Later in May, an F-5E flown by Maj. Mohammed Yâhya ash-Shami was downed by anti-aircraft fire. In June, two YARAF F-5Es successfully shot down a Southern MiG-21 flown by Maj. Abdul Habib Salah. Following the brief conflict, which resulted in a Northern victory and reunification of the country, the remaining F-5s were incorporated into the Yemeni Air Force.

F-5Es were used extensively by Yemeni forces against Houthi rebels — Shiite rebels with links to Iran — during the Houthi insurgency, which began in 2004 and lasted well into 2014. In 2015, following indications that at least some members of the YARAF had switched allegiance to the Houthi movement, a YARAF F-5E was destroyed by Saudi Arabian forces during an airstrike.

More recently still, visuals of Houthi rebels having flown at least one aging F-5 have circulated online. That aircraft was spotted making a surprise appearance at a military parade in September.

According to the 2023 World Air Forces directory, the YARAF currently has 11 active F-5Es and two F-5B trainers.

So there you have it, the crazy history behind Yemen’s small F-5 fleet.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com