The U.S. Army says it has gotten rid of its entire fleet of Airborne Reconnaissance Low-Enhanced aircraft, or ARL-Es, and is now in the process of divesting dozens of smaller Enhanced Medium Altitude Reconnaissance and Surveillance System types, or EMARSSs. The service is planning to supplant these and other existing fixed-wing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft with a new fleet of business jet-based designs. However, the intended replacements are still years away from becoming operational in significant numbers.

A spokesperson for the Army’s Program Executive Office for Aviation (PEO-A) confirmed to The War Zone today that all ARL-E aircraft, also known as RO-6As, were removed from service by the end of 2022. It’s unclear what the exact size of the ARL-E fleet was at its peak last year, with the service having at least six of these aircraft as of 2015 and prior plans to acquire a total of nine.

Whatever the case, all but one of those aircraft are no longer in the service’s inventory at all. The remaining example has been repurposed as a “flight test asset,” according to PEO-A

The ARL-Es were based on the de Havilland Canada DHC-8-315 twin-engine turboprop, a series of aircraft that are often referred to collectively as Dash-8s. These aircraft were created by converting what had previously been Army-owned and contractor-operated DHC-8-315s in a number of other intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) configurations to a new common standard. The ARL-E configuration featured a mixture of still and full-motion video cameras, imaging radars, and signals intelligence systems, as you can read more about here.

In August 2022, the Army did announce that Dash-8 aircraft in the Saturn Arch configuration, one of the types that were folded in ARL-E, had completed their final missions in support of U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM). It’s unclear whether this means that those aircraft were never fully converted into the RO-6A configuration before they were divested.

“The Army Fixed Wing Project Office did receive orders directing the divestment of the EMARSS fleet,” the PEO-A spokesperson further confirmed. “Army staff are doing the work required to coordinate that effort and do not have additional information to share at this time.”

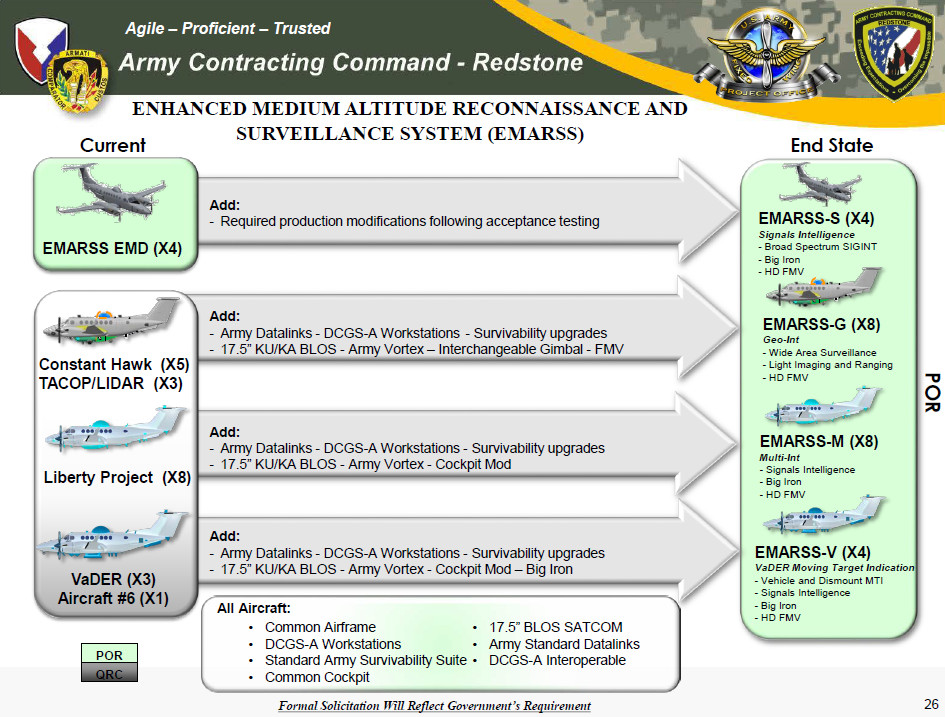

All of the EMARSSs are based on the Beechcraft King Air 350 twin-engine turboprop and are also designated as MC-12Ss. However, this fleet consists of aircraft in four distinct configurations with differing sensor packages. These include various mixtures of still and full-motion video cameras, imaging radars and lasers, and signals intelligence suites, as you can learn more about here.

At present, there are around 23 EMARSS aircraft in Army inventory. Another EMARSS plane crashed in Iraq and was written off in 2020. None of the individuals onboard that aircraft at the time of the mishap sustained any major injuries, according to the U.S. military.

The ARL-E and EMARSS fleets represent a plurality, if not a majority, of the Army’s fixed-wing ISR aircraft. The service has another 19 RC-12X Guardrail Common Sensor (GRCS) planes, also based on King Air-series turboprops. Of these, 14 have a signals intelligence package and a ventral sensor turret with electro-optical and infrared full-motion video cameras, while the other five are pilot trainers with no sensors at all.

An unknown number of de Havilland Canada DHC-7 four-engine turboprop-based EO-5C Airborne Reconnaissance Low-Multifunction (ARL-M) aircraft, also known by the program nickname Crazy Hawk, which the ARL-Es were intended to replace, remain in service, according to PEO-A. As of 2015, the Army had at least eight EO-5Cs and there are three currently in the boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona.

A fourth DHC-7 that had been contractor-operated in a different configuration from the ARL-M, known as the Medium Altitude Reconnaissance and Surveillance System (MARSS), is also at the boneyard. A second MARSS DHC-7 that was placed in storage there in 2019 was removed from the official public boneyard inventory sometime between September and October 2022 for unclear reasons. The War Zone previously did a deep dive into these two aircraft.

At present, the Army’s stated goal is to eventually replace all of its remaining RC-12X GRCS, MC-12S EMARSS, and EO-5C ARL-M aircraft with a still uncertain number of ISR-configured business jets under the High Accuracy Detection and Exploitation System (HADES) program. There are, however, significant questions about the specifics of the Army’s aerial ISR plans and how the Army expects to execute them.

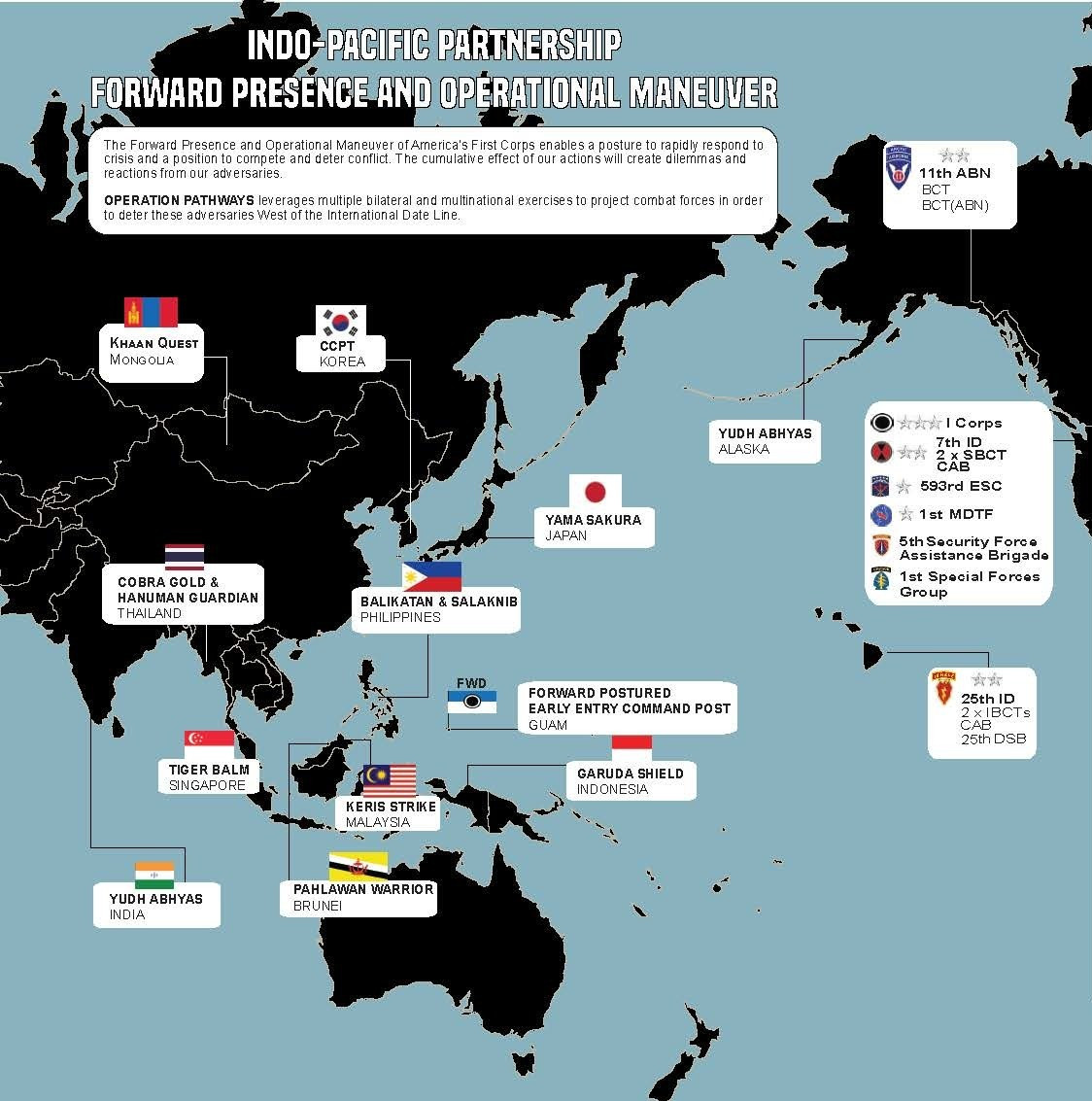

“The need for greater speed, range, altitude and convergence capability is driving the Army towards a modernized capability that can see further and more persistently than ever before,” the PEO-A spokesperson told The War Zone. “This is critical for our U.S. Army Pacific and U.S. Army Europe Theater Army commanders.”

“For the Theater Army commander in the Indo-Pacific, this geography extends from the Arctic to the tropics, the breadth of which vastly exceeds the capabilities of our legacy ISR fleet,” they added.

The Indo-Pacific region, broadly, is currently the main focal point for U.S. military planning amid rising challenges posed by the Chinese military and geopolitical friction with that country’s government. This was all underscored just recently by what U.S. officials said was a Chinese government spy balloon that passed through U.S. and Canadian airspace before being shot down over the Atlantic Ocean on February 4, as you can read more about here.

There are certainly benefits that business jet-based platforms offer over turboprop types, including in terms of speed, overall range, and maximum operating altitude. Those capabilities translate to improved flexibility, especially when it comes to self-deploying to forward locations and getting on station faster, as well as increasing the standoff range and collection area of various onboard sensors. Shorter transit times can help improve the overall sortie rate for these aircraft, too.

Being able to fly higher and collect intelligence while operating further away from the target would help give the jets improved survivability compared to their turboprop counterparts. They would have the ability to leave an area faster if threatened, as well. Given that business jet-based aircraft are still non-stealthy, relatively unmanueverable, and not capable of high speeds, questions remain about just how much more capable they might be in higher-threat environments. This is especially true in very high-threat environments where even with their increased performance, they would likely be pushed back far beyond their collection range due to advanced, long-range enemy defenses. The Air Force abandoned its business jet-based replacement for its E-8 JSTARS radar aircraft largely due to this reality.

Survivability considerations are especially important as the U.S. military, as a whole, seeks to better prepare itself for future high-end conflicts, including against potential near-peer adversaries, such as China. Aircraft like the ARL-E and EMARSS, in particular, trace their roots to the height of active U.S. combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Their careers have seen them fly exclusively in permissive airspace.

However, the Army has insisted in the past that the RC-12X GRCS, specifically, together with established concepts of operation, can provide help with “targeting of near-peer threats in an Anti-Access Area Denial (A2AD) environment.” Guardrail variants have been deployed in Europe and on the Korean Peninsula for decades now with the expectation that those aircraft would support any major conflict in those theaters.

That being said, the Army did bring RC-12X operations in Europe to an end in January. In that region, online flight tracking software shows that contractor-operated jets associated with an Army program called the Airborne Reconnaissance and Targeting Exploitation Multi-Mission Intelligence Systems (ARTEMIS) have now taken over GRCS’s routine flights around Russia’s geographically separated and highly strategic Kaliningrad enclave, among other things.

There is simply a matter of general capacity, as well. As it stands now, the Army appears to have at least two contractor-operated business jet-based ISR aircraft that are flying under ARTEMIS, as well as at least one as part of a separate program called the Airborne Reconnaissance and Electronic Warfare System (ARES). The service plans to acquire additional contractor-flown ISR jets under a third program called Army Theater Level High-Altitude Expeditionary Next-Generation AISR (ATHENA).

Though these aircraft are conducting operational missions, the Army views them as demonstrators that will help feed into the HADES program, which still has yet to be fully defined. The service has said in the past that it expects to acquire between 10 and 16 HADES jets – a fleet that could potentially absorb the ARTEMIS, ARES, and ATHENA aircraft – and have the first examples in service by 2028.

Though perhaps more capable in certain regards than their turboprop counterparts, each one of these jets still cannot physically be in more than one place at one time. Even if the 16 HADES aircraft are primarily tasked to support operations in the Pacific and Europe, this leaves questions about how the Army will meet aerial ISR demands in other regions. ARL-E and EMARSS aircraft, in particular, have been employed in the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America in recent years.

Crewed fixed-wing assets from other services, as well as uncrewed platforms, along with contractor-operated aircraft, could make up for at least some of the aerial ISR shortfall in many of these contexts, which involve more localized flights in largely permissive airspace.

U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) notably has its own fleet of fixed-wing ISR aircraft, including Dash-8-based types often mistaken for RO-6As and others based on the King Air series, as well as various drones, that already operate regularly in these regions. On the other hand, the U.S. Air Force has also just cut a fleet of similar aerial ISR aircraft, the RC-26B Condor, with no plans to acquire a direct replacement.

The Army did, of course, choose to pursue a similar plan in the 2000s and early 2010s, only to eventually decide there was a need to consolidate capabilities and bring them under more direct service control. This is what prompted ARL-E and EMARSS in the first place.

It is more likely than not that greater clarity on the Army’s aerial ISR plans will be included in its budget request for the 2024 Fiscal Year, a public version of which should be coming in the next month or so. Details about ARL-E divestiture plans were notably absent from its Fiscal Year 2022 or 2023 budget proposals.

What is clear is that the Army is already moving ahead with plans to divest a significant portion of its fixed-wing ISR aircraft while the expected replacements are still years away from entering service.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com