South Korea’s KF-21 next-generation fighter is preparing for its first flight, with footage of a prototype undertaking ground tests under power having emerged in the last few days. These tests follow recent static engine runs for the twin-engine fighter, the first flight of which is rumored to be planned before the end of this month.

Undated but apparently recent videos taken from outside the Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI) production facility in Sacheon show the first prototype KF-21 — named Boramae, meaning hawk in Korean — taxiing across a temporarily closed road. The KAI facility is collocated with Sacheon Airport, which serves the city of Jinju in the southeast of the country. Reports indicate that the jet was heading north from the KAI plant to the airport’s main runway. Once there, the test pilot opened the throttles of the U.S.-supplied General Electric F414-GE-400K engines, and the aircraft made a brief high-speed run before decelerating. This kind of test run is entirely expected bearing in mind the potentially imminent nature of the aircraft’s first flight.

Unconfirmed reports suggest that the KF-21’s maiden flight could now take place as soon as July 22. A total of six flying prototypes are scheduled to be completed, with assembly work now well underway on at least the second, third, and fourth.

Late last month, official videos appeared showing the first prototype undergoing static engine tests, with its landing gear harnessed to the ground in a test hall at Sacheon. Both engines were apparently spooled up to full power with full afterburner selected.

Prior to these latest landmarks, assembly of the first prototype had begun in 2020, with the roll-out taking place in 2021, an event we reported on at the time.

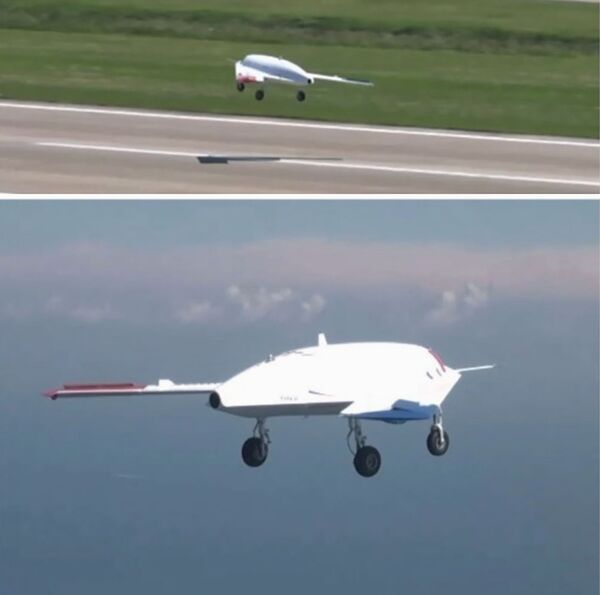

The first KF-21 prototype under construction in Sacheon:

Seoul is developing the KF-21 to replace the aging Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) F-4E Phantom II and F-5E/F Tiger II fighters. Under current plans, the ROKAF is expected to induct 40 KF-21s by 2028 and have a full fleet of 120 aircraft deployed by 2032. Another 50 of the jets are expected to be ordered by Indonesia, which is a junior partner in the program although, at times in the past, its commitment to the KF-21 has been questioned. Ultimately, the KF-21 program is expected to have an estimated total value of $7.4 billion.

Overall, this is an aggressive schedule for a modern homegrown fighter program. That the prototype is already conducting ground tests with engines (and presumably other primary subsystems) up and running suggests that it might not be entirely unrealistic, however.

After all, KAI has, for the time being at least, foregone a high degree of stealth attributes that characterize the F-35, for example, which has also been procured by South Korea. These challenging requirements need to be considered in almost every aspect of an aircraft’s design and tactics and add considerably to overall costs, as well as the support burden.

Indeed, the KF-21 takes a more measured approach to low-observable design and is intended to bridge the gap between the F-35 and the fourth-generation F-16, in terms of capabilities. At first, the KF-21’s weapons will be carried externally, on six underwing and four under-fuselage hardpoints, unlike in the F-35 and most other next-generation fighters, which incorporate internal weapons carriage primarily to reduce their overall radar signature.

Ultimately, once in service, work is expected to begin on a more advanced derivative that will have an internal weapons bay, among other new low-observable features. In this way, the initial KF-21 will likely have around the same radar cross-section as Eurofighter Typhoon, before later enhancements reduce this significantly.

What is more, the KF-21 will initially be fielded in a Block 1 variant that will have an air-to-air capability only, while the subsequent Block 2 will be cleared for air-to-ground missions. This is another significant difference from most of the Boramae’s contemporaries, which typically strive to include multirole capabilities from the outset.

What’s interesting, though, is just how South Korea is expecting to employ its KF-21s in an operational context.

Seoul’s unique approach to its new fighter trades a high degree of stealth for what should be a lower-cost platform, with some low-observable features, but which eventually could operate closely with stealthy platforms to boost its combat efficiency. As an adjunct to the F-35, for example, the ROKAF’s KF-21s could carry a greater number of weapons, including larger ones, than a Joint Strike Fighter will with an internal ordnance load.

At the same time, even in its basic form, the KF-21 will have a smaller radar signature than the ROKAF’s 60 multirole F-15K Slam Eagles, advanced versions of the F-15E Strike Eagle, and its more numerous F-16C/Ds, which are now in the process of being upgraded to the F-16V standard, with new avionics.

However, as well as cooperating with the ROKAF’s F-35s, the KF-21 is being touted as a candidate to work alongside homegrown stealth drones.

A short video, prepared last year by the Defense Acquisition Program Administration, or DAPA, which manages South Korean defense procurement, uses computer-generated sequences to reveal details of some of the KF-21’s missions and weapons.

As well as takeoff, aerial refueling from a KC-330 Cygnus tanker, and launch of a long-range Meteor air-to-air missile (AAM), the video shows a KF-21 flying alongside three stealth drones.

Interestingly, the jet seen in the video is a single-seater, although a two-seat variant is planned and an additional crewmember for the ‘loyal wingman’ drone-controller mission appears to be a preference in at least some countries, including China, where a two-seat J-20 stealth fighter apparently intended for this mission broke cover last year.

“If the project goes smoothly, and when the indigenous jets are deployed, they may carry out missions with unmanned aircraft someday,” an official from DAPA said at the time, according to a report from South Korea’s Yonhap news agency. While the unnamed official may have been speaking deliberately cautiously, it’s no secret that Seoul is working on stealth drone programs.

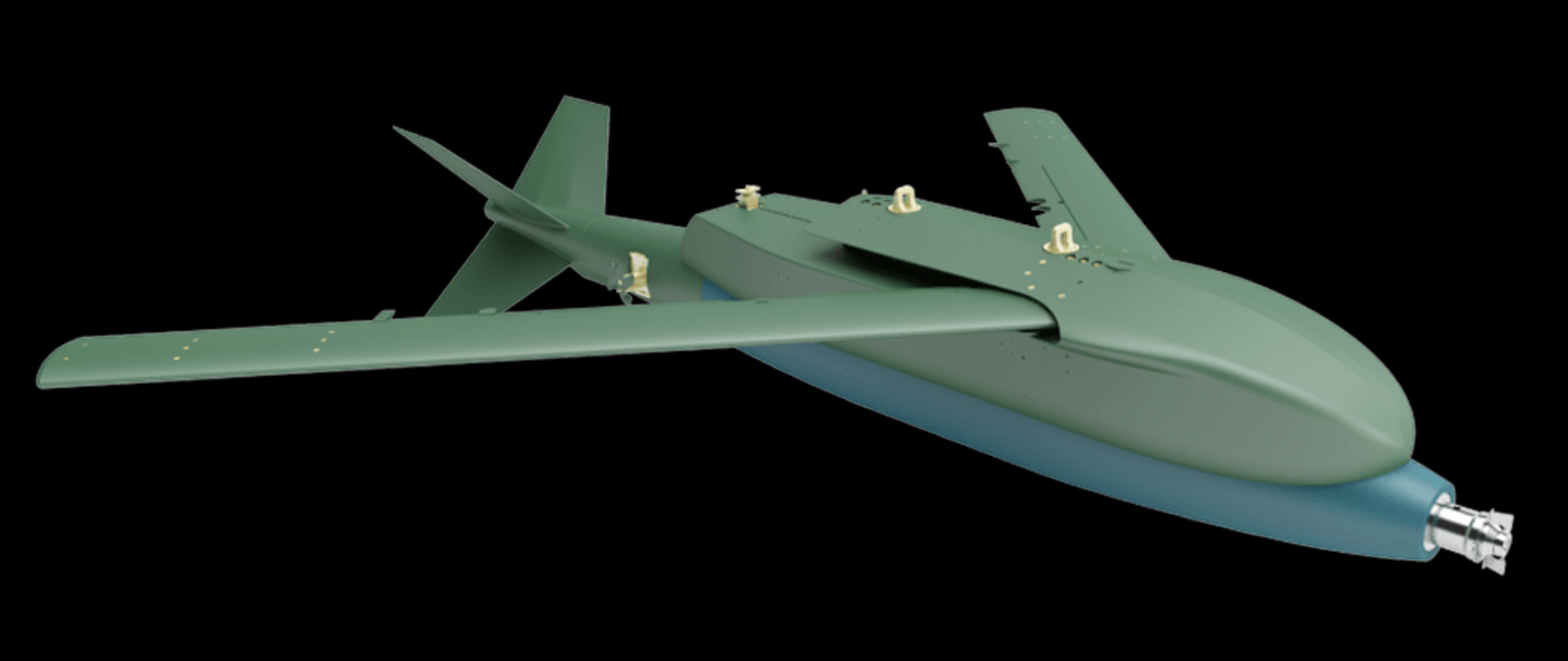

The three stealthy drones seen in the DAPA video are of a tailless flying-wing design, with an engine intake located above the forward fuselage, a configuration that’s similar to various other comparable UCAV designs around the world. It’s unclear to what degree these DAPA depictions would actually match a potential production stealth drone, but they do share broad characteristics with previous South Korean UCAV designs.

For some years now, Korean Air Aerospace Division, or KAL-ASD, has been working on a stealthy unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV) under the KUS-FC program. A subscale demonstrator, the Kaori-X, began flight testing in 2015. This demonstrator has reportedly been used to test low observability, aerodynamic control and stability, and propulsion concepts.

In September last year, South Korea’s Agency for Defense Development (ADD) announced that it had mastered critical technologies to allow the production of full-size stealthy UCAVs, the result of a project launched in 2016. In particular, the agency pointed to the development of aerial structures, including radar-absorbent material, plus flight control algorithms that would help reduce a drone’s radar cross-section (RCS). The ADD also described these features being incorporated in a tailless unmanned aerial vehicle. Reports suggest that this effort is separate from, but complements the KUS-FC program.

At the same time, Seoul is also working on the technologies required for manned aircraft, like the KF-21, to operate in close conjunction with drones as part of a collaborative team.

In October 2021 it was announced that Korea Aerospace Industries (KAI), which is leading the KF-21 program, had won a $3.4-million contract from DAPA to rapidly develop a new manned-unmanned teaming (MUM-T) system. Due to be completed in December 2022, this will initially be used to support joint operations involving South Korean battlefield helicopters, such as the Surion and the Light Attack Helicopter (LAH), and undisclosed drones. The plan is for the helicopters to directly control drones and to receive real-time imagery from these UAVs to support their mission. American Apaches and Gray Eagle drones deployed to South Korea have a version of this capability now, which likely helped spur this development locally.

Potentially, the broader MUM-T technologies at play could subsequently be adapted for future integration of the KF-21 and UCAVs.

Having a stealth drone available as a ‘loyal wingman’ for the KF-21 would appear to make a lot of sense. As mentioned previously, the initial iteration of the KF-21 does not have the high-end stealth attributes of say the F-35.

And with the KF-21 to be fielded initially in the air-to-air-only Block 1 variant, a UCAV capable of carrying offensive munitions becomes even more useful as an adjunct to the manned fighter. This would allow the drone to prosecute ground targets that have been identified by the manned fighter, for instance.

As well as already fielding a wide variety of Western air-to-ground weapons, Seoul is developing its own precision-guided ordnance, at least some of which could be suitable as UCAV armament, as well as for the KF-21. This includes the Korean GPS Guided Bomb (KGGB) guidance kit and wing kit for the 500-pound Mk 82 bomb with a maximum range of 62 miles and a smaller version of the European TAURUS KEPD 350 cruise missile that is expected to have a range of around 250 miles.

More generally, a stealth UCAV carrying internal weapons would be an enormous advantage to the KF-21 Block 1 or Block 2 when penetrating heavily contested airspace. This would allow the manned fighter to remain at a safer standoff distance and use its highly capable Meteor missiles and active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar and infrared search and track (IRST) to pick off aerial targets. This could be done perhaps by targeting data received from the UCAV’s own sensors without the need to use the KF-21’s onboard radar at all. This concept is increasingly attractive as it could allow manned fighters to remain largely electromagnetically silent, increasing their survivability, with the drone taking on the higher-risk role as a forward sensing platform.

Work on the KF-21’s locally developed AESA radar — a collaborative venture between Hanwha Systems and LIG Nex1 — is also apparently gathering pace. This program has been making use of a modified Boeing 737-500 airliner, operated by South Africa’s Aircraft Instrument and Electronics, as the testbed. This aircraft completed five sorties from Seoul Incheon International Airport last month alone, based on publicly available flight-tracking data.

A Block 2 version of the KF-21 would also be able to launch standoff missiles against ground targets, again using coordinates provided by an F-35, stealthy drone, or by other means, perhaps responding to hostile air defenses deliberately triggered by a UCAV’s presence.

High-end capabilities of that kind also point to potential adversaries beyond North Korea. Intriguingly, the aforementioned DAPA video shows the KF-21 and UCAV team operating over the Dokdo Islands, also known as the Liancourt Rocks, which are at the center of a long-running territorial dispute between South Korea and Japan. These countries have rival claims on the islets, which are surrounded by rich fishing grounds as well as oil and gas reserves.

The requirement for increasingly advanced capabilities to keep pace not only with North Korea but also with China and Japan means that a sovereign asset like the KF-21 — especially one that can work alongside a stealth UCAV — could be in great demand for the ROKAF and for the wider South Korean military.

The KF-21 could also find a niche in the export market. Almost certainly, the KF-21 will be cheaper to operate than the F-35 and won’t require such extensive supporting infrastructure. It will also avoid the strict export restrictions imposed on the Joint Strike Fighter program. As to whether it could find a market as an F-16 successor among the many global Viper operators, much will depend on the final unit price and operating costs of the jet.

Nevertheless, the ability to bring to market a homegrown capability of this kind, together with homegrown AESA radar, speaks to the overall competencies of the South Korean aerospace industry.

Clearly, Seoul has outlined an ambitious timeline for getting its KF-21 into service, although incorporating more modest capabilities in its initial production configuration should help meet this target. The latest evidence of ground tests confirms that the program is indeed making important progress.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com