The Peruvian Navy has given an intriguing glimpse of how sonar imaging is used to locate stricken submarines stranded on the sea floor. Rescuing submarines is incredibly complicated, often requiring specialized assets above and below the ocean’s surface, with time being the biggest enemy to success.

Pictures taken by Peru’s Navy show the use of sonar imaging as part of a recent mock submarine search-and-rescue exercise. This drill forms part of the 2023 iteration of Peru’s SIFOREX (Silent Forces Exercise) — an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) exercise that began on October 20 and is slated to end on October 27.

SIFOREX 2023 is taking place within an operational area located 50 miles from the Port of Callao on Peru’s central coastline, and aims to increase interoperability between the Peruvian and U.S. Navies. SIFOREX, which was first held in 2001 and has run biennially since 2006, primarily focuses on ASW operations, but also spans anti-surface warfare (ASuW) and submarine escape and rescue (SMEREX).

During the search-and-rescue demonstration, Buque Armada Peruana (Peruvian Navy Ship, or BAP) Carrasco, one of Peru’s six scientific research vessels, attempted to locate a ‘stricken’ submarine disabled on the sea floor. That submarine, which can be seen in the pictures released by Peru’s Navy, was BAP Pisagua, a Type 209/1200 diesel-electric submarine developed in Germany.

According to a machine translation of a social media post by the Peruvian Navy, the training event allowed “technology to be tested on board [Carrasco]… which precisely explored the seabed with its multi-beam echo sounder and side scanning probe.”

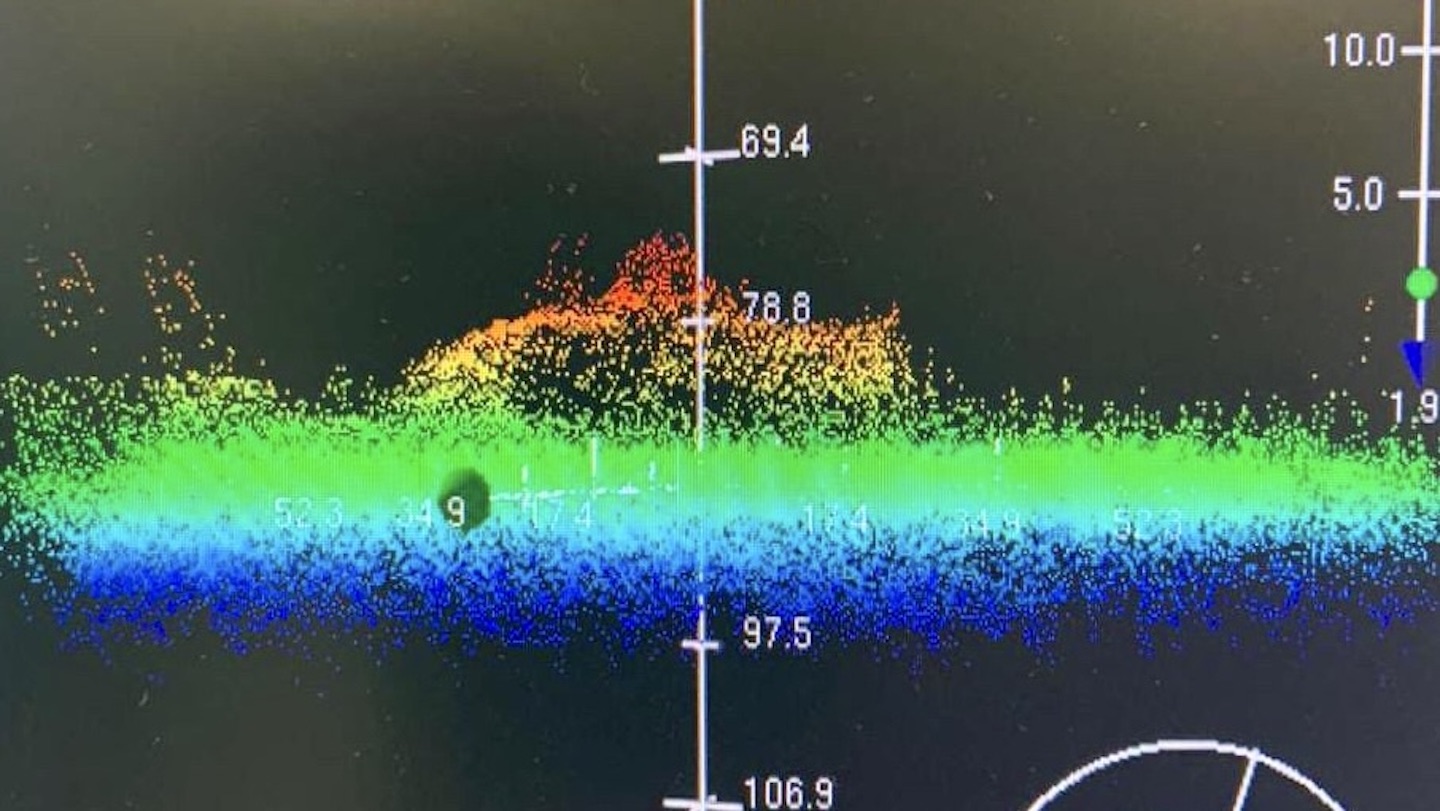

What’s most striking about the images is how well Pisagua can be made out by the equipment on Carrasco. For context, the submarine is nearly 60 meters long, with its beam measuring 6.4 meters. But depending on the nature of the sea floor, such a target can be very hard to spot. In this case, we see the submarine’s general outline and shape pretty well defined in the side-scanning sonar and other types of advanced sonar imagery collected by Carrasco. This includes what looks like a 3D scan, where its sail and hull shape can be seen contrasted against the seafloor. This technology can be critical to executing a successful rescue, as diving on a false target can mean the difference between life and death for a submarine crew. Also, knowing the general orientation of the submarine can help mission specialists to best devise a plan to execute a rescue or recovery operation.

Commissioned in 2017 and constructed by Spain’s Freire Shipyard, Carrasco is just over 95 meters long and has a displacement weight of 5,000 tons. According to Peru’s Hydrography and Navigation Directorate, the vessel has been primarily utilized for oceanographic and polar research. However, the organization does list it as a rescue vessel with “SAR [search-and-rescue] capabilities” and advanced sonar technologies.

For those new to the topic, make sure to read this previous War Zone piece by a retired U.S. Navy submarine sonarman explaining the science behind sonar and its use for detecting submerged objects.

Much of Carrasco‘s equipment is manufactured by Norway’s Kongsberg Maritime. This includes the company’s 12 kilohertz EM 122 multi-beam echo sounder, which is designed to perform seabed mapping to depths of 11,000 meters. In addition, Carrasco also utilizes Kongsberg’s SBP 120 sub-bottom profiler, which, in conjunction with the EM 122, provides imaging of sediment layers and buried objects beneath the sea bed to depths of 500 meters. The full list of technical equipment aboard Carrasco is as follows, quoted from Peru’s Hydrography and Navigation Directorate:

- Multibeam echo sounder EM122 deep water KONGSBERG (11,000 meters)

- KONGSBERG Deep Sea Single Beam Echosounder

- SBP 120 KONGSBERG Profiling Echosounder (penetration up to 500 meters)

- Sub-Bottom Profiler

- One remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), 1,000 meters Falcón DR

- Wave Gilders with meteorological, oceanographic, AIS sensors

- Two ADCP of 38 and 300 kilohertz

- EK-60 Scientific Fishing Echosounder (with 5 transducers 18, 38, 70, 120 and 200 kilohertz)

- One Explorer Pro Magnetometer

- Piston Corer (5,000 meters deep)

- Oceanographic Rosette of 24 Niskin bottles

- Two KONGSBERG Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV)

Even under optimal training conditions like that of SIFOREX 2023, locating missing submarines is difficult. But this becomes all the more complex when subs, both military and commercial/private types, go missing at the bottom of the ocean for real.

In comparison to the exercise, real-life search-and-rescue missions often require scouring large swathes of the ocean for a missing submarine. It remains a difficult task even when searching shallow waters. As such, they frequently necessitate pooling the capabilities of surface vessels, underwater vehicles, and aerial assets, often from different countries.

Moreover, once a missing submarine has been successfully located, there are further complications in rescuing the personnel on board. Specialist assets are needed for deep-sea rescues in particular. The U.S. Navy, for example, boasts a range of rescue capabilities for those situations, including the Submarine Rescue Diving Recompression System (SRDRS). As The War Zone has noted previously, SRDRS and other rescue systems are operated by the Navy’s Undersea Rescue Command (URC). URC is postured to be able to load its systems onboard airplanes within 24 hours of receiving notice of a missing American or foreign submarine.

Being able to dispatch rescue equipment swiftly is critical for any submarine rescue attempt. As soon as a sub goes missing, it’s immediately a race against time to try to find it, and if possible, rescue its crew. Nuclear submarines can add another critical facet to these operations to contend with — the state of the boat’s reactor.

Thanks to the Peruvian Navy, we now have an interesting view of how such rescue operations look to those individuals scouring the sea floor for signs of stricken submarines.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com