Iran has offered Russia “hundreds” of drones, including armed ones, for use in its war in Ukraine, according to the U.S. government. To date, Ukraine has taken a leading role in using armed drones in the conflict, although Tehran also has considerable experience with such designs, and how to use them. Iranian armed drones would give the Russian side new options for carrying out strikes, including targeting higher-value assets deep in Ukraine. Moreover, Iran providing drones of any kind to Moscow would also be a significant statement of political intent.

Speaking to reporters last night, Jake Sullivan, the White House national security adviser, claimed that “the Iranian government is preparing to provide Russia with up to several hundred UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles], including weapons-capable UAVs, on an expedited timeline.”

Details of that timeline were not revealed, but Sullivan did add that U.S. intelligence indicated that Iran was preparing to train Russian forces to use these drones “as soon as early July.”

The offer of drones, armed or otherwise, has been rebuffed somewhat by Iranian officials. However, Nasser Kanaani, an Iranian foreign ministry spokesperson, told Iran’s semi-official Tasnim news agency: “The history of cooperation between Iran and Russia in the field of some modern technologies dates back to before the war in Ukraine.”

“There has been no particular development in this regard recently,” he added.

In the wake of Sullivan’s statement, there has been speculation that Russian could be lining up a purchase of Iranian-made armed drones in the same broad category as the TB2, i.e. unmanned aerial vehicles which can carry disposable armament as well as targeting sensors and which can return to base after their mission.

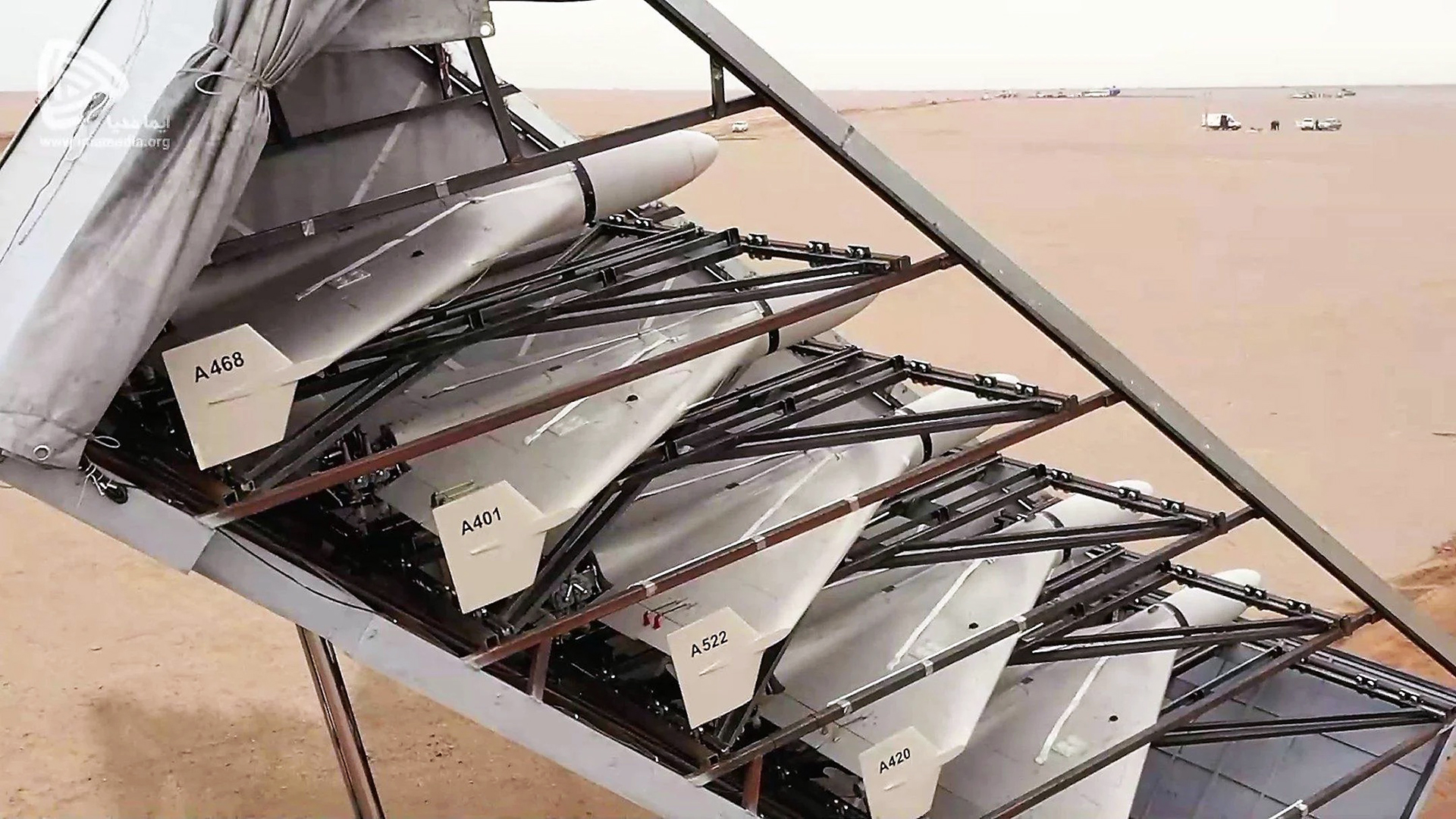

However, the reference to “several hundred UAVs” sounds much more like a smaller type of UAV, perhaps the kind that has become widely known as a ‘suicide drone’ or ‘kamikaze drone’ on account of its one-way mission.

There are multiple examples in the Middle East of Iranian-made suicide drones, including those operated by Iran and its proxies targeting oil infrastructure in Saudi Arabia, causing significant damage in sometimes-complex raids. The vulnerability of infrastructure, in particular, to these sorts of ‘low-end’ drone attacks is a topic we have explored in the past. Such attacks have also been prosecuted by a combination of suicide drones as well as ballistic and/or cruise missiles, making defense against them even more problematic.

Even used on their own, these kinds of drones are by no means straightforward to counter using traditional air defenses and, in all, they can have a destructive effect that’s entirely at odds with their relatively low cost of procurement.

Russia has so far not made such extensive use of armed drones in the conflict, despite having developed several of its own and having employed these, at least on a trial basis, during its campaign in Syria. Russian UAVs have, however, been widely used for surveillance over Ukraine.

As a means of prosecuting long-range attacks, Iranian armed drones would be much cheaper than using cruise or ballistic missiles. Furthermore, Russia’s capacity to produce such weapons in the face of sanctions is also questionable. While the Iranian-made suicide drones would lack some of the sophistication and reduced radar cross-section of the latest Russian cruise missiles, they would be highly suitable for the same kinds of pinpoint attacks on infrastructure. Their range would also mean they could be used against targets in western Ukraine, including the capital, Kyiv. Even using them indiscriminately as a sort of ‘vengeance weapon’ on the capital is a real possibility. Considering Iran has built up its own aerospace industry in the face of sanctions and major import restrictions over the years, the serial production of drones is unlikely to be impacted as weapons manufacturing in Russia currently is. In fact, Iran could become a key source for weapons of various types for Russia as the country continues to be hit by the double impacts of heavy sanctions and global supply chain issues.

Reports of depleted Russian weapons stocks have become familiar since early on in the conflict in Ukraine, with standoff offensive weapons seemingly being particularly hard hit, a result of a campaign of long-range strikes across Ukraine. An apparent lack of more advanced standoff missiles, like the Kalibr series, is very likely behind Russia’s recent decision to employ Kh-22 (or Kh-32) missiles, better known as anti-ship weapons, against targets on land, for example. In another recent development, Russia is reportedly also now employing S-300 series surface-to-air missiles in a land attack role.

Meanwhile, Ukraine has made extensive use of Turkish-supplied Bayraktar TB2 armed drones, in particular, bringing these into action against pro-Russian forces even before the invasion began. In the process, the TB2 has been elevated to near-iconic status for the Ukrainian side, aided considerably by its use in high-profile operations like repulsing the Russian assault on Kyiv, and the repeated Ukrainian attacks on Snake Island in the Black Sea. More recently, however, it seems that the use of the TB2 has diminished, mainly as losses have mounted in the face of Russian air defenses.

In the Ukraine war, too, we have seen the use of suicide drones for long-range strikes, with an attack on a Russian oil refinery in the Rostov region. This may well have been carried out by an adapted, commercially available product that is sold on the Chinese marketplace website Alibaba.

That may not be the only instance of Ukraine repurposing a drone of a different kind for a one-way attack mission against a Russian target. Last month, a Ukrainian Tu-143 jet-powered drone, dating from the late Cold War era, was reportedly shot down in western Russia. Meanwhile, a similar-looking but larger Tu-141 drone that crashed in Croatia in March reportedly carried an explosive warhead. Taken together, these incidents suggest Ukraine may well be adapting these unmanned aerial vehicles as high-speed suicide drones for long-range strikes.

Even today, reports emerged from Ukraine claiming that its forces had used drones of an undisclosed type to attack Russian troops in Russian-occupied Enerhodar, in the northwest of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, further reinforcing the importance of armed UAVs to the Kyiv regime.

The apparent use of suicide drones by Ukraine in some of these examples also points to another advantage of this type of drone strike, in that it’s very possible to at least obscure the identity of the perpetrator. This could be especially attractive for Moscow since attacks on Ukrainian targets by Iranian-made drones could be officially attributed to pro-Russian separatist forces already active in Ukraine. This level of plausible deniability could also open up the option of attacking more sensitive targets — the kinds of raids that have led to widespread international condemnation.

There is also the possibility that Russian could exploit Iranian expertise to prosecute different kinds of drone strikes, including against maritime targets if the need arises, for example, if the conflict expands into the strategically vital Black Sea. Tehran has much experience in this area, having attacked, or coordinated attacks, on commercial shipping on a number of occasions in the past. In August last year, for example, U.S. Central Command released details of a fatal drone attack on a Liberian-flagged, Israeli-operated tanker, M/T Mercer Street, off the coast of Oman. Iran was blamed for that incident, which involved three strikes carried out by “one-way attack unmanned aerial vehicles,” better known as suicide drones.

Other Iranian drones have been developed specifically to seek and destroy air defenses, in the same kind of role that was first pioneered by the Israeli-developed Harpy drone. This could be of particular relevance to Russia as it seeks to further degrade the Ukrainian air defense network, especially as new kinds of surface-to-air missiles begin to threaten Russian aircraft. Degrading Ukraine’s air defenses via anti-radiation seeker-equipped drones could help open up the airspace in the western part of the country for attacks by traditional manned assets.

With all this in mind, it is clear that acquiring Iranian armed UAVs, especially suicide drone types, in such large numbers, could be very attractive for Russia. Indeed, according to Iranian reports, Russian interest in buying its drones — or perhaps licence-producing them — dates back to 2019, at least a year before the UN arms embargo on Iran was lifted.

Then there is the issue of what Tehran stands to gain from a possible deal of this kind. Securing a hugely valuable new customer — one that is fighting an active all-out war no less — for its arms comes at a time when sanctions have taken their toll and cash infusions are much needed. It would also send a powerful signal of its support to the Moscow regime, which has found itself more or less an international pariah since invading Ukraine in February this year. Tehran has already said it blames NATO expansion in Eastern Europe for triggering the war in Ukraine.

As to getting Iranian drones to Russia, that would likely make use of an already established pattern of cargo flights between the two countries. According to data gathered by aircraft tracker and satellite image analyst Gerjon , in the first three months following the invasion of Ukraine, at least 23 Iranian cargo flights flew from Iran to Moscow. Exactly what these aircraft were transporting remains unclear, but all seem to have landed in Moscow and were flown by airlines that have been understood to have transported arms to other countries in the past. In particular, some of the same aircraft and airlines were noted flying to Ethiopia immediately before Iranian-made Mohajer-6 drones appeared in that country.

There is also the option of delivering weapons by sea. According to a report yesterday from the semi-official Mehr News, Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) is shipping 300 “special containers” containing undisclosed goods to Russia. The same statement noted that, if demand increases, the number of containers can also grow.

However they are supplied, getting drones into Russian hands quickly could be of great value. The Iranian drone portfolio, by and large, is heavily focused on systems that smaller militaries or even non-state actors can be trained to use quickly. On the whole, they also require minimal logistics, which would be another boon for Russia and its much-publicized logistics issues.

With all this in mind, the timing of this disclosure could also be significant, since it comes only two days before U.S. President Joe Biden begins a tour of the Middle East. This is planned to include visits to Israel and Saudi Arabia with the aim of developing a military alliance with these nations that will be aimed squarely at countering the threat from Iran. Notable, too, is the fact that Israel, formerly lukewarm as regards support to the Ukrainian war effort, announced the delivery of military materiel for Kyiv soon after the announcement of possible Iranian drones for Russia.

In NATO and the United States, therefore, Iran and Russia have a common foe.

Next week, meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin is expected to visit Tehran, where a sale of drones or other military support may well be on the agenda. Putin and Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi also plan to discuss the civil war in Syria with President Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey. Turkey, for its part, has supplied Ukraine with the aforementioned TB2 drones, as well as supporting Syrian rebels fighting against the Syrian government regime, which is backed by Russia and Iran.

If Russian does indeed get its hands on large quantities of Iranian drones, it could mark a significant shift in the war in Ukraine, with Tehran’s entry into the arena as a potentially significant political player. At the same time, should Russia start deploying Iranian-made suicide drones, as seems entirely possible, it will further reinforce the fact that we are very much entering a new age of warfare, in which standoff strikes by one-way drones are an increasingly common — and challenging — dynamic.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com