Whether we’ve failed to control them or whether they’re simply beyond our control, circumstances have a curious way of reminding us of the options we once had to help us solve the problems we face. Today, the U.S. Navy’s questionable anti-submarine warfare (ASW) readiness, the circumstances for which it has failed to control, has a group of U.S. Marine Corps and Navy officers calling for a return to an option that was used back in the early 1970s — tactical jets as submarine-hunters.

When I was researching my previous article for The War Zone on the Navy’s experimental use of tactical aircraft (TACAIR) to support the anti-submarine effort by dropping sonobuoys and relaying the acoustic data, I hadn’t even considered there might someday be a call to enlist F-35s and F/A-18s to do that and more. But that is just what Captain Walker Mills, U.S. Marine Corps, and Lieutenant Commanders Collin Fox, Dylan Phillips-Levine, and Trevor Phillips-Levine, U.S. Navy, suggested in their article, “Use Emerging Technology for ASW,” in the October 2021 issue of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings.

Cold War carrier sub-hunters

As I explained in the previous story, by the mid-1960s, the aging, cumbersome, and radial-engined S-2 Tracker couldn’t keep up with the nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSN) and the various anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) carrying submarines (SSG/SSGN) of the Soviet Navy. However, the Tracker’s replacement wouldn’t begin joining the multirole aircraft carrier fleet until 1974. The twin-turbofan S-3 Viking promised faster speed, longer range and loiter time, an advanced acoustic processor, and a greater load of sonobuoys for a far more effective search, localization, and tracking of any submarine threat.

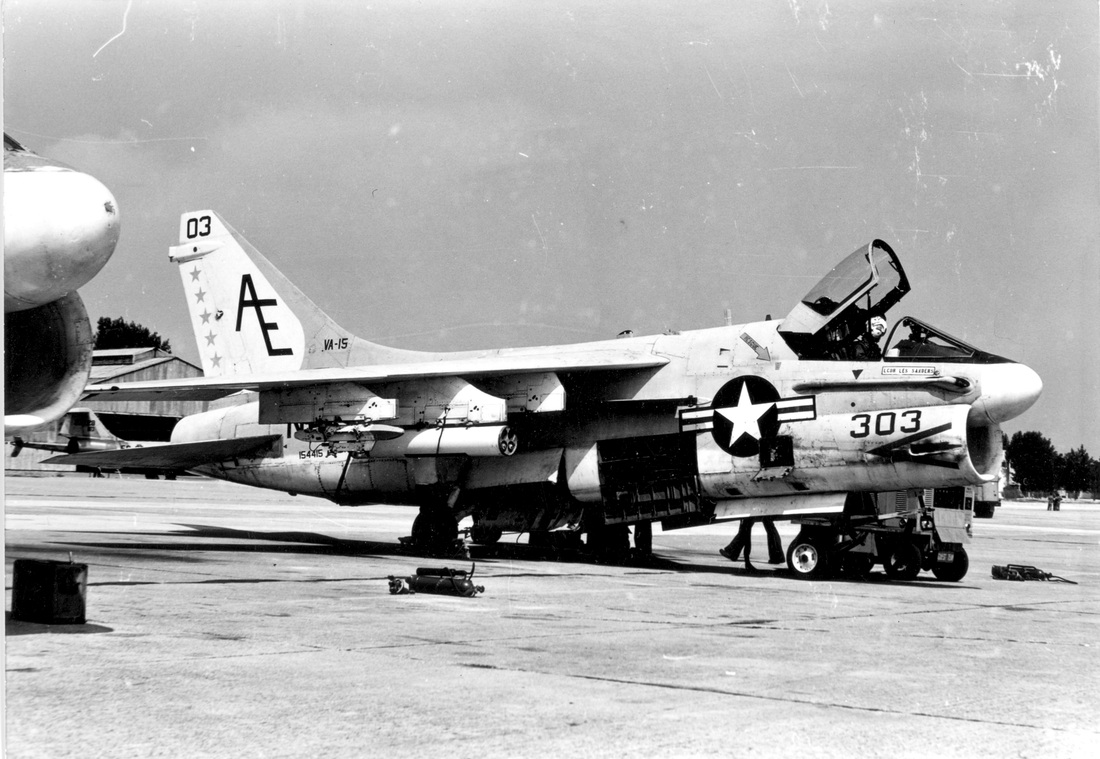

As a stopgap measure, the Navy decided to experiment with using TACAIR to enhance the carrier battle group (CVBG) commander’s ASW capabilities with fast jets that could drop sonobuoys from a fuel-tank-sized pod mounted on one of the wing or centerline hardpoints. Another pod relayed the acoustic data produced by the deployed sonobuoys back to the carrier or other ASW-capable ships for analysis. Of course, the A-7 Corsair IIs and A-6 Intruders could also deliver an impressive amount of ordnance should a submarine reveal itself at periscope depth or on the surface.

Today, unfortunately, there is nothing to wait for. There is no fixed-wing, carrier-based ASW miracle just a couple of years away from joining the Fleet that can complement and relieve the extremely over-tasked P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft and the over-used MH-60R Seahawk helicopter.

F-35s and Hornets, oh my!

“The Navy needs new and innovative anti-submarine warfare platforms to defend against China’s stealthy and potent long-range threat,” the authors of the Proceedings article contend. They know a Viking-like aircraft is not in the Navy’s cards, so from their own innovative hand, they recommend that the Navy reach back 50 years and resurrect the concept of using TACAIR for the ASW mission. These fast-moving aircraft could cover the vulnerable mid to outer defensive zone of the carrier strike group (CSG) and expeditionary strike group (ESG).

Unlike the historical effort that had TACAIR crews merely dabbling in the dark art of ASW with simple buoy drops and relay duty, these authors suggest going even further:

“…a section of F/A-18s or F-35s configured for ASW could assume the role of the retired S-3 Viking and bring organic, fast, and long-range ASW back to the carrier air wing. An airborne ASW patrol could help pinpoint the target location with IRST [infrared search and track], defeat inbound missiles with its own air-to-air missiles, and quickly reach the target area to both conduct an urgent attack and then deploy a range of sensors for follow-on prosecution. Rather than simply reinventing the S-3B on a new airframe, the Navy should use F/A-18s and F-35s to leverage smarter sensors, unmanned technology (including MQ-25s as wingmen), and novel weapons to attack distant submarines. However, because they lack the S-3’s long loiter time, they would need a new toolkit of persistent, mobile sensors and over-the-horizon relays to enable new operational concepts.”

Much of ASW, in war and peacetime, has been conducted using the ‘flaming datum’ method where the first indication anti-submarine forces have of a submarine’s presence is when the convoy or high-value unit they’re protecting has been hit by a torpedo (or annoying green flare).

What the authors of the Proceedings piece suggest is something remarkable: using TACAIR to detect the launch of incoming ASCMs, try to defeat them, and then go after the firing submarine.

Since the dawn of the missile in naval warfare, it has been a waiting game: waiting for the missiles to get within radar detection range with the hope to destroy them, at what amounts to a very dangerous range leaving little room for failure. Additionally, unless ASW assets had already localized the submarine before it released its weapons, the fog and chaos of war ensured the chances of finding and retaliating against the offending target diminished rapidly or completely if critical ASW platforms were damaged or destroyed.

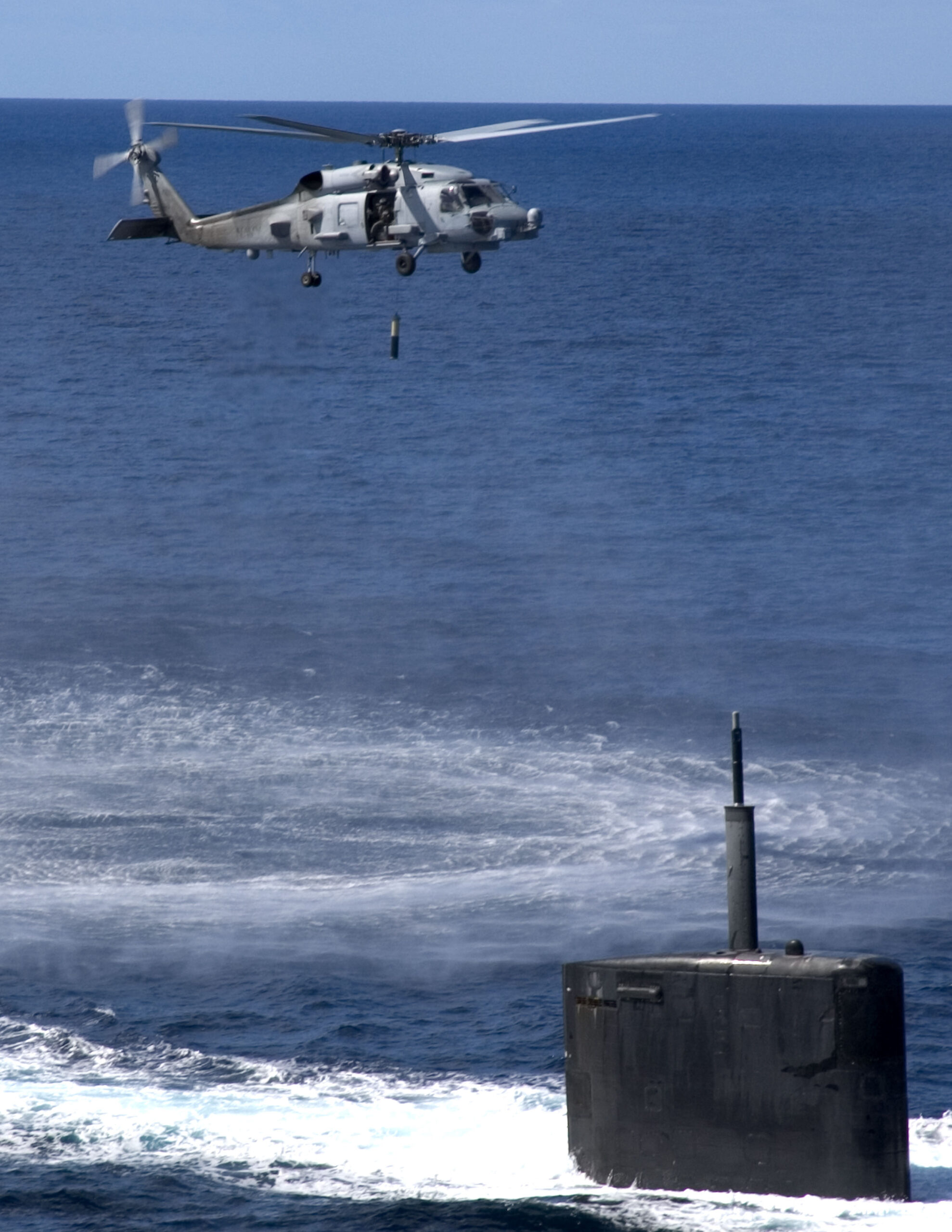

Due to the neglectful situation the Navy finds itself in today, any idea to enhance the Fleet’s ASW capability should be taken seriously. Remember, the MH-60R is the sole organic CSG and ESG airborne anti-submarine asset. Ironically, like the S-2 Tracker then, the Seahawk “simply lacks the range, speed, and payload to conduct extensive searches at the ranges needed to protect the group from submarine-launched ASCMs” now, as the authors relate. Finding threat submarines anywhere within the ASW defensive zone, localizing, and then killing them must be an all-hands effort.

And on the subject of sinking, inflicting a mission kill, deterring, or otherwise occupying a threat submarine, if an unmanned helicopter from the 1960s — the QH-50C Drone Anti-Submarine Helicopter (DASH) — can drop a lightweight ASW torpedo on a detected submarine, there’s no reason why an F/A-18 or F-35 can’t deliver a Mk 54 torpedo, particularly of the High-Altitude Anti-Submarine Warfare Weapon Capability (HAAWC) variety. Even several Very Lightweight Torpedoes (VLT) could be carried by the fighters. If the Falklands War can teach the twenty-first century U.S. Navy any lesson, it should be how much ASW ordnance will be spent in the next war at sea.

Shortly after the Proceedings article was published, I noticed some criticism of these ideas from social-media ‘navalists’. Expecting the same from the article’s online comments section, I was pleasantly surprised to find an A-7 pilot, who had dropped sonobuoys from his Corsair II, supporting a contemporary use of TACAIR for the ASW mission.

The curious incident of the Zuni rocket pod that launched sonobuoys

Retired Captain Robert “Barney” Rubel, a 30-year Navy veteran and professor emeritus at the Naval War College (NWC), flew A-7s from the deck of the USS Independence (CVA-62). Commenting about the Proceedings article, he wrote:

“We actually practiced a form of what the author suggests… USS Independence deployed as a CVA on her 75-76 cruise… We modified Zuni [five-inch rocket] pods to pop sonobuoys out the back (eight per pod) and modified a drop tank with a radio relay. We installed the relay pod on the duty tanker and put the sonobuoy pods on the A-6s and A-7s doing SSSC [Surface, Subsurface, Surveillance, and Control missions]…”

My research had originally indicated that the USS Saratoga (CV-60) was the only aircraft carrier used for this TACAIR ASW experiment.

More interesting still, using A-7s and A-6s for sonobuoy drops was still an option after the S-3 began joining the Fleet. Captain Rubel was kind enough to respond to my email inquiry and provided more detail about the process:

“I did airdrop some sonobuoys and carried a relay pod when I drew the duty tanker hop… As far as the buoys go, we just selected the weapons station, master arm, and then pressed the pickle switch to get two of them to eject out the back of the Zuni pod. The ASW Module guys instructed us on how to lay [buoy patterns] and we used our inertial [navigation] system to put them where ordered. When tasked with ASW, we normally carried two pods of buoys for a total of 16.”

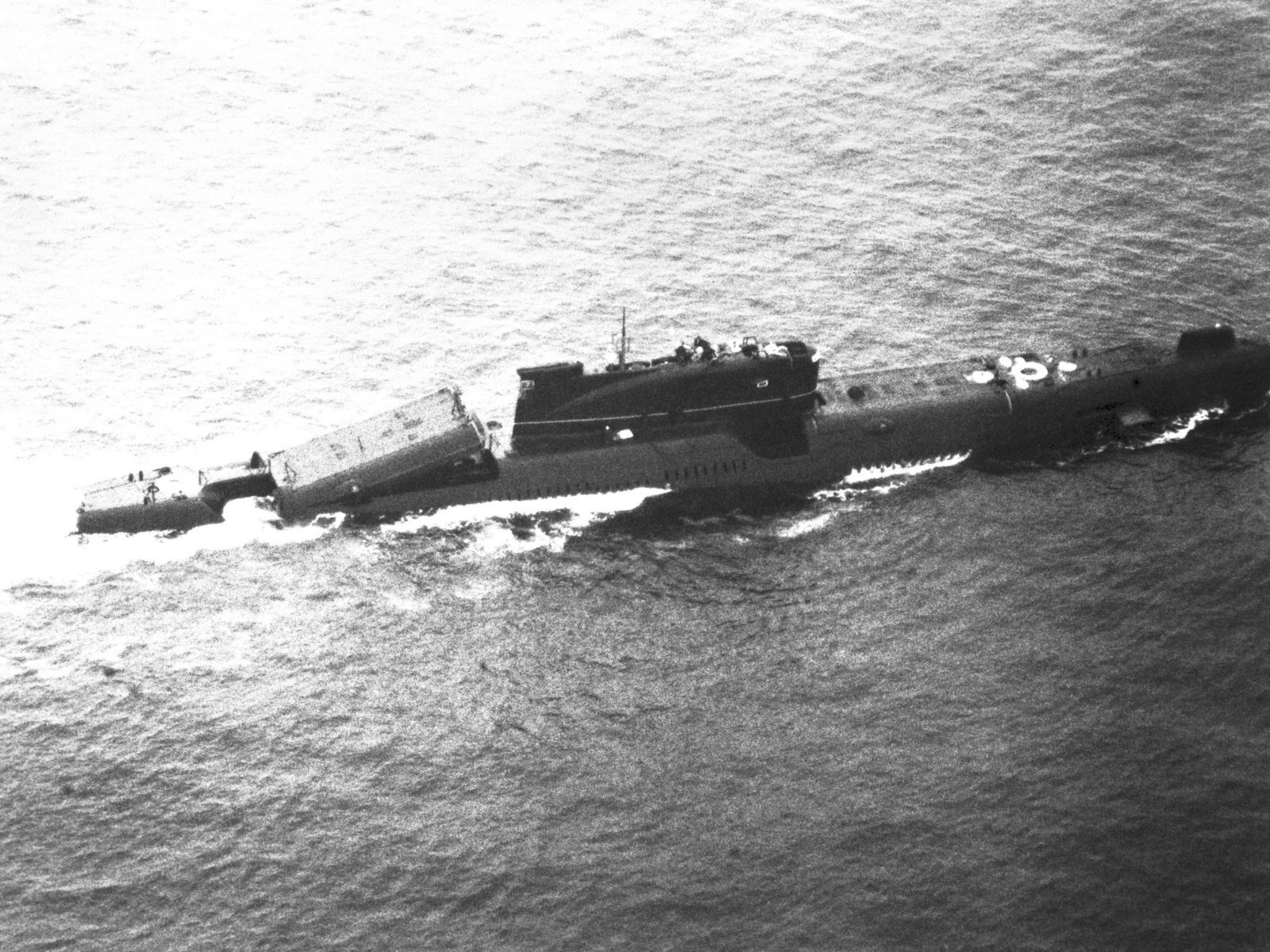

The TACAIR pilots got to participate in the hunt for a real-world Soviet submarine. Rubel explained how a Soviet Juliett class SSG had been discovered in the Ionian Sea, in the Mediterranean, while attempting to snoop on a NATO exercise. Not having a Tracker or Viking squadron on board Independence during the cruise, the Corsair IIs and Intruders were tasked to drop buoys and they successfully “herded it away.”

Knowing the non-sexy nature of ASW, I asked Captain Rubel how he and his fellow A-7 pilots felt about this type of mission. “I never heard anyone complain…” he wrote back. “It really didn’t interfere with anything because we normally fanned out for SSSC duty to identify distant radar contacts the E-2 [Hawkeye] found.”

Rubel’s larger point about why the TACAIR pilots were fine with doing the SSSC and ASW mission was inspiring: “Besides, after the encounter with the Soviet Med Eskadra in late ’73, we were all about war at sea and ASW fit right in.” He was referring to the U.S. Sixth Fleet standoff with the Soviet Navy Mediterranean squadron, or eskadra, during the Yom Kippur War which is described in detail in the NWC article “The Tale of Two Fleets.”

And the surprises kept on coming. One of our own TWZ commentariat, “N-Drive,” brought to my attention how AV-8 Harriers were also armed with sonobuoy pods.

So easy, a Harrier pilot can do it

The U.S. Marine Corps began operational use of the AV-8A, the American version of the remarkable British-built Hawker Siddeley Harrier, during a time when the Navy was seriously considering building Sea Control Ships (SCS). Conceptually, the SCS was a small-deck carrier that was to be used as an escort to provide air and ASW support for convoys, underway replenishment ships, amphibious groups, and other high-value units. The Harriers would be used primarily for strike and air defense while protecting and assisting the SH-3 Sea Kings as they performed the ASW mission.

A paper written by Ocean Specialist Second Class (OS2) Michael Smialek — who served aboard the Iwo Jima class amphibious assault ship USS Guam (LPH-9) that was acting as an interim SCS during its 1974 Mediterranean deployment — describes how the small carrier was tasked to deploy sonobuoy barriers just inside the Gibraltar Strait. This was a notorious choke point for submarines as you can read all about here. The sonobuoy laying was in anticipation of the arrival of a Soviet SSN.

“The majority of the sonobuoys were passive and dropped in various patterns from the SH-3G helicopters and sometimes from the Harriers” of VMA-513 “Flying Nightmares” which was the Marine Corps squadron detachment that flew alongside the Sea Kings from the “Red Lions” of HS-15 (italics added by the author).

USS Guam was a relatively slow amphibious assault ship, only capable of 23 knots maximum speed. Soviet SSNs were much faster and could easily outpace the ship. As the submarine they were tracking began to distance itself from the carrier and the effective range of the SH-3s, “…we might send out the Harriers to drop sonobuoys 50-100 miles away from the Guam in the direction we believed the sub was headed.”

ASW is not an unprecedented mission for the Marines. Few remember that during World War II, the Marine Corps flew anti-submarine patrols in the Caribbean and the Pacific against German and Japanese submarines. Amid a furor over what mission the Marine Corps should be performing in the 21st century, MV-22 Ospreys and helicopters are increasingly dropping buoys in support of naval efforts to defeat the submarine. As with Harrier ops from USS Guam, it would be highly interesting to see F-35Bs supporting the ASW effort.

UH-1Ys are also already experimenting with this capability, which could be a value-added proposition when they are embarked with an ESG or are conducting Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO). The UH-1Y’s attack counterpart, the AH-1Z, could also potentially play a role, even when it comes to the kinetic end of the anti-submarine kill chain. New anti-ship concepts of operation, along with a slew of upgrades, including full Link 16 datalink capability, would put them in a unique position to do so alongside the UH-1Y. The Navy’s MQ-8 Fire Scout drones are also platforms that can assume some ASW duties. Still, these are helicopters and lack the speed and range of a fixed-wing anti-submarine platform.

The Q-9 Reaper drone family has also developed the ability to drop sonobuoys and relay their data. While the Reaper is not a carrier-based aircraft, they could also potentially help in this regard and there are concepts on the drawing board that could make them carrier capable.

The Navy is in trouble

Like generals, admirals are always getting ready to fight the last war. And that’s the Navy’s problem: not only has it allowed its ASW skills to atrophy over the past three decades but it has wasted those decades not preparing for the undersea war to come. Thus, it should come as no surprise that younger officers, forced to work with platforms and concepts originally designed to fight the Soviet Navy, are having to consider ideas that were truly innovative — back in 1971.

Unfortunately, the belief that an ASW-configured F-35 or F/A-18 could “assume the role of the S-3 Viking,” as the authors claim, is unfounded. The complexities of anti-submarine warfare demand a dedicated, carrier-based, fixed-wing aircraft with the range, endurance, and sensor/weapons loadout to cover the mid to outer ASW zone. The F/A-18, F-35B/C, and the MQ-25 simply are not this.

In reality, TACAIR aircraft flying from an aircraft carrier have far more important missions to do than ASW. With the rise of the Chinese Navy, the proliferation of advanced diesel-electric submarines, and the challenges posed by a resurrected Russian Navy, the U.S. Navy should have been focusing on a direct replacement of the S-3B Viking. Perhaps the CMV-22 Osprey or a modified E-2D airframe could be used as an interim option until the best platform could be designed and developed for the CSG.

Until then, distributing the ASW burden throughout the Fleet in as many imaginative, effective, and realistic ways must be considered and accomplished long before a flaming datum makes us wish we had done so. Therefore, the two fighters should become a critical part of a well-thought-out and well-trained CSG/ESG anti-submarine mission.

Kevin Noonan served in the U.S. Navy from 1984–94 as a sensor operator (SENSO), briefly, in the P-3B Orion with VP-94 and for the remainder of his service as a SENSO in the S-3A/B with VS-41, VS-24, and VS-27.

Contact the editor: thomas@thedrive.com