The U.S. Navy is set to demonstrate the ability of an uncrewed underwater vehicle, or UUV, to launch and recover a smaller drone that can both swim and fly. The service says it wants the two platforms to be able to go through the deployment and retrieval processes autonomously — without any human involvement.

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) announced today that it had hired SubUAS to “develop and demonstrate launch and recovery capabilities of the Naviator from and to a UUV (using a UUV surrogate).” The total value of the contract, which was formally awarded on November 8, is nearly $3.7 million, if all options are exercised.

What ONR is currently referring to as the Subsurface Autonomous Naviator Delivery (SAND) system must be able to launch and recover the Naviator “without a human-in-the-loop,” according to a brief statement about the deal with SubUAS.

The Naviator drone at the center of this project is a known quantity and has been in development since the early 2010s, in part with the help of U.S. military funding through the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. SubUAS was founded in 2016 to handle continued work on the Naviator, which was originally created by a team led by F. Javier Diez, an associate professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

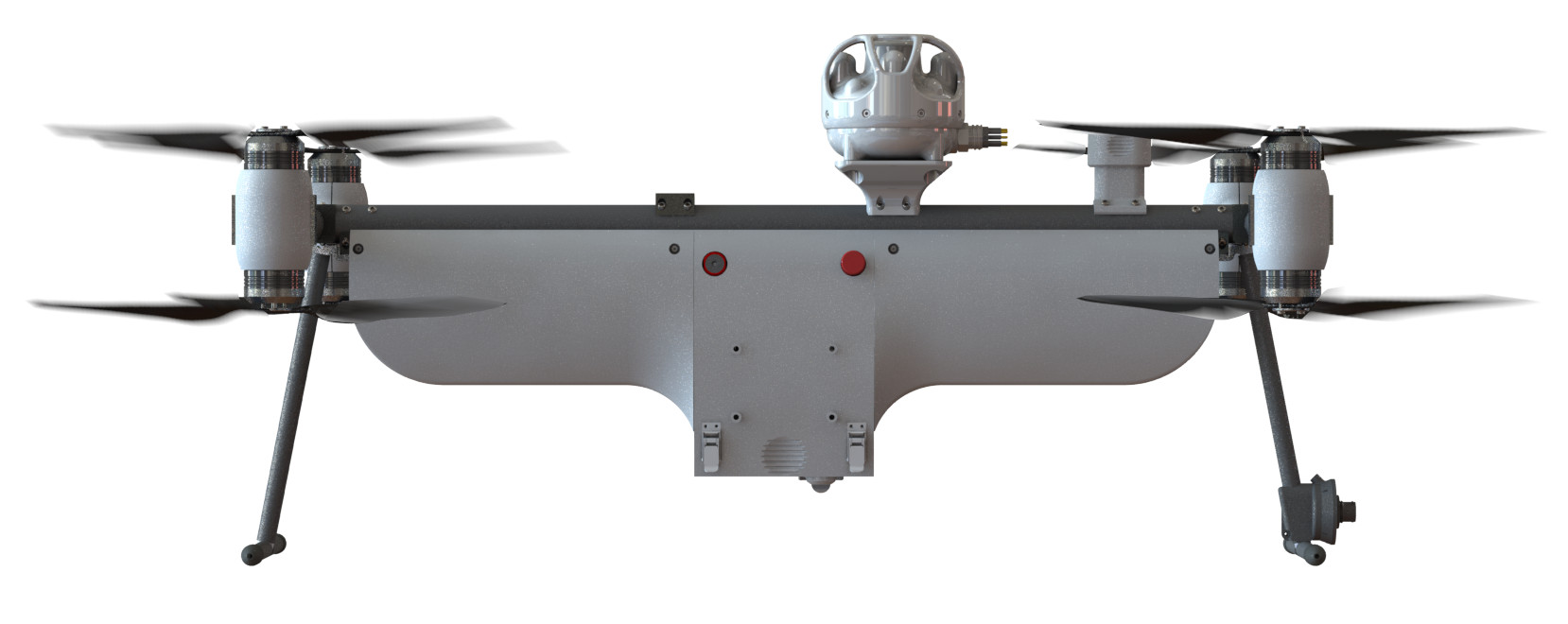

At a quick glance, the Naviator looks a lot like a typical quadcopter drone. However, is designed specifically to be able to pull itself along underwater, as well as fly, and transition seamlessly from one medium to the other. As seen in the pictures throughout this piece, a number of iterations of the uncrewed aerial system have been developed over the years and SubUAS describes the platform as scalable.

“Naviator is scalable to multiple sizes, with a 16-foot wingspan and 0-90+ lbs payload, and is optimized for a variety of sensors, cameras, and other payloads. Naviator is faster to deploy than existing underwater Remote Operating Vehicles (ROVs), and is also able to reach its target faster via flight,” according to a 2020 U.S. government press release. “It has longer embedded mission capabilities than similarly sized drones, and utilizes precise GPS and visual position hold, as well as power-saving buoy sentry mode. The platform can easily surface, send data, receive new instructions, and begin a new mission.”

The same release also said that Naviator was capable of “tetherless operation with remote pilot control, and the ability to conduct autonomous missions.” SubUAS’s website notes that smaller versions of the drone could be used in swarms.

SubUAS has said in the past that existing Naviator types are capable of reaching underwater speeds of up to 3.5 knots, and could potentially get up to 10 knots depending on their size and configuration. It’s unclear how fast the drone can fly in its aerial mode.

The ONR contract notice today does not provide details on the capabilities of the specific Naviator design it plans to test or what type of UUV mothership it might intend to represent using the unspecified “surrogate.” However, it’s not surprising that the Navy is interested in this kind of capability.

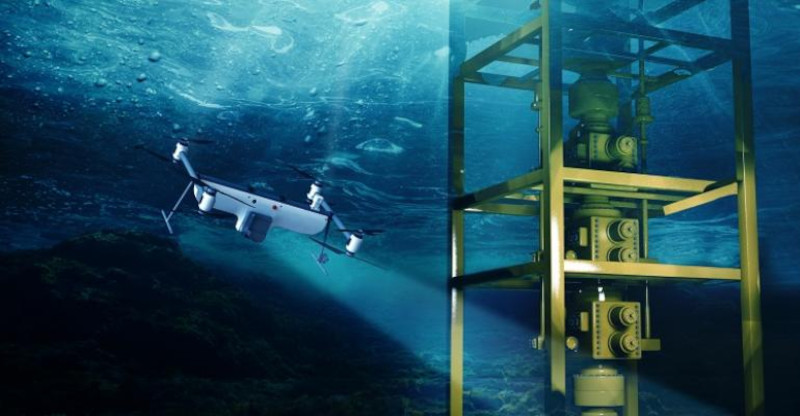

“Mines are probably the biggest problem for the Navy,” Diez, the professor at Rutgers behind the Naviator design, said back in 2015. “They need to map where mines are. Now there are a lot of false positives. This could be a better technology to rapidly investigate these potential threats.”

In a naval context, “the drones could emerge quickly from the depths, get a quick glimpse of enemy ship deployments, and then hide again,” a news item from Rutgers at that time further noted. “An air-and-water drone could also help engineers inspect underwater structures, such as bridge and dock piers, ship hulls and oil drilling platforms.”

In this role, Naviator could help protect friendly forces by checking the hulls of ships and coastal infrastructure below the waterline for evidence of mines being placed or other signs of hostile infiltration.

Naviators could help with search and rescue missions, too. “For instance, the vehicle could scan the water from above to locate missing swimmers and sailors, and upon spotting shipwreck debris could dip underwater to further examine the scene,” Rutgers’ 2015 news item notes.

There are also various potential civilian scientific research and commercial applications for the Naviator.

For the U.S. Navy, being able to employ Naviators in swarms and deploy them discreetly using UUVs, which themselves could be launched via crewed submarines, opens up additional possibilities and offers additional operational flexibility. For instance, a swarm of Naviators could scour a broader area around the UUV for threats and do so relatively rapidly.

The UUV’s ability to launch and recover the aerial drones without any need for immediate, direct human involvement only increases the ability of the pairing to operate autonomously forward of other friendly forces. This is fundamental to an advanced UUV’s mission set.

The requirement for the Naviators to be recoverable and their quadcopter-like design imposes certain limitations, including in terms of range, endurance and applicable mission sets. Tasks like conducting swarming non-kinetic and kinetic attacks on enemy forces, using payloads like electronic warfare jammers or small munitions, or even acting as a ‘kamikaze drone’ that just smashes into its target and explodes would be better left to longer-range fixed-wing drone platforms that are not necessarily intended to be retrieved afterward. That’s not to say Naviators couldn’t do some of these things, but just in much closer proximity to the launching UUV than other alternatives.

The range issue would also be mitigated to some degree by advanced UUV’s ability to slip deep into denied or otherwise sensitive areas before launching the drones to perform any assigned missions closer to their targets than what any other launch platform could provide.

The Naviator’s highly autonomous capabilities would also be critical to not being detected and not needing to communicate with the launch platform for much of its flight. While extending a communications mast or buoy and connecting to the drone is clearly possible, that would increase the risk of detection greatly to the UUV. By sending the Naviator on its way and recovering it after its mission and then downloading its intelligence products, both drones can stay effectively silent throughout the sortie, only communicating during recovery operations.

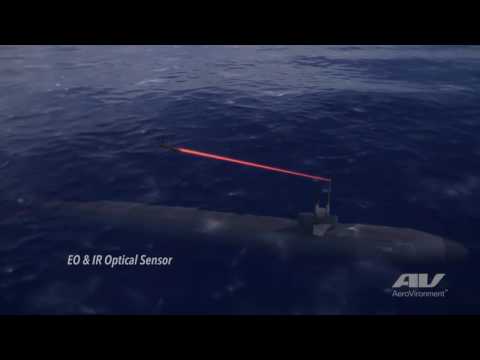

ONR’s SAND concept is, of course, not the first time, even recently, that the Navy has announced plans to demonstrate underwater-launched uncrewed aerial system capabilities.

In 2021, ONR awarded a separate contract to Raytheon to demonstrate its ability to launch versions of its Block 3 Coyote drone configured as loitering munitions, also known as kamikaze drones, from UUVs and uncrewed surface vessels (USV). The same year, the Navy announced its intention to buy unarmed 120 AeroVironment Blackwing submarine-launched drones. American submarines have had a proven ability to launch smaller fixed-wing drones for surveillance for many years now.

The Navy also said just last week it hopes, as part of a program called Razorback, to begin fielding a new UUV that can be launched and recovered using the torpedo tubes on its existing crewed submarines within a year. This follows the cancellation of the Snakehead UUV program last year in part due to that design being too large to find inside a standard torpedo tube, limiting the options for deployment and retrieval. The Navy has developed other torpedo-tube-launched drones in the past, but these have typically not been readily recoverable by the same means.

Another Navy program, called Orca, is also pushing ahead with the development of a large-displacement UUV that is not intended to be launched or recovered via a torpedo tube. The Navy also has various smaller UUVs in service and in development.

In recent years, the U.S. military has been exploring options for launching aerial drones configured to perform various missions, including in swarms, from a host of other platforms, including ground-based systems, crewed surface warships, traditional fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, and even high-altitude balloons.

It remains to be seen what will come from the Navy’s new project to launch and recover Naviators from other underwater drones, and do so without the need for direct human involvement. What is clear is that this effort is completely in line with the kind of capabilities the service is pushing to field in the near term.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com