The Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, Gen. David Allvin, caused something of a stir this week when he talked about his service already looking at what it would buy after the B-21 Raider stealth bomber, which is still years away from entering service. Allvin seemed non-plussed about the prospect of buying more than the 100 B-21s the USAF currently aims to procure, hinting that the service is eying something new. While it may be striking to some that the USAF is not seeking to double down on the B-21 and conform to calls to build dozens more of the stealth jets, Allvin’s comments should not have been surprising in the least. They actually make perfect sense.

Gen. Allvin made his remarks about the future of America’s bomber force in response to questions about interest in buying more than 100 B-21s during a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on April 16. The Air Force’s current plan is to acquire at least 100 Raiders, but there have been discussions for years now about purchasing many additional examples – some advocates have proposed fleet size numbers as high as 250, which is unrealistic. The first pre-production B-21 only flew for the first time last November and is now undergoing initial flight testing. Five more pre-production Raiders are in various stages of construction. Low-rate production of B-21s has now also started and the goal is to begin fielding the type operationally before the end of the decade.

“With regard to the family, the B-21 family, right now the actual platform itself, we’ve ordered or we’re prepared to purchase 100. Would you say that is the minimum number needed of the base platform?” Sen. Mike Rounds, a South Dakota Republican, asked Allvin yesterday.

“It [the B-21] certainly is the future of our bomber force. … 100 is the program of record,” Allvin said. “I think we’re not going to reach that number until probably the mid-2030s and beyond. And before we commit to that as being the platform beyond that, I think there are other technological advancements that we would see to be able to augment that and have a better mix.”

It is important to note up front that Allvin did not in any way suggest the Air Force’s plans to acquire at least 100 B-21s, already a relatively large number of these highly advanced and capable stealth bombers, had changed or that there is any expectation now that they will have shorter service careers than previously expected. He pointedly used the term “augment” when talking about what the service might decide to purchase instead of more Raiders down the road.

It is equally worthwhile remembering that the core B-21 design has been in development for nearly a decade that we know about. It is widely understood to make significant use of mature or at least semi-mature technologies to help reduce cost and complexity, and thus lower risk. It is also an aircraft that has been able to leverage Northrop Grumman’s considerable past experience with the design and production of aircraft like this, including lessons learned from the B-2 program and even earlier concepts. Still-classified aircraft, likely including a stealthy high-altitude, long-endurance (HALE) drone commonly referred to as the RQ-180, are also posited to have contributed to the Raider’s development.

None of this is to say that the Raider is simply a ‘B-2 2.0,’ something The War Zone has addressed in detail in the past. The B-21 is expected to be extremely capable, especially in terms of its broadband stealth characteristics and its range performance, and be able to perform missions well beyond long-range strike.

At the same time, the Raider reflects a deliberate decision on the part of the Air Force to pursue a lower-cost option, relatively speaking, with at least some reduction in capability requirements in 2009 with its transition from the Next Generation Bomber (NGB) program to the Long Range Strike-Bomber (LRS-B) effort. NGB, often colloquially referred to as the “B-3,” itself traced its routes back to a 1999 Air Force white paper on future bomber force planning. Northrop Grumman won the LRS-B competition in 2015 leading, which resulted in the B-21.

So, when Gen. Allvin says B-21 production is likely to hit 100 airframes sometime in the latter half of the 2030s, at the earliest, that will be at least two decades after the contract award and even longer after the development of the Raider is known to have begun in earnest. It will also be around a decade and a half after a baseline variant design was finalized enough to begin low-rate production. Altogether, this is not at all an unreasonable timeframe, with the Air Force now thinking about what might augment or even ultimately supplant B-21 production. As the Air Force Chief of Staff highlighted at yesterday’s hearing, it is possible, if not highly probable, that new technology advances made in that time will significantly impact the Air Force’s future planning, and not just regarding bomber fleets. It would be pretty safe to say that this has already begun.

Just in terms of bombers and other long-range strike capabilities, the service is expecting to fly dozens of re-engined and otherwise significantly upgraded B-52s through at least 2050. These iconic aircraft are being retained in large part for the design’s unique ability to lug around outsized payloads like novel hypersonic weapons. There is also the Rapid Dragon palletized munition system that is designed to turn cargo aircraft into impromptu stand-off strike platforms, as required, and do so on the cheap. So the USAF will have less complex ‘weapons trucks’ available for decades to come.

When it comes to buying B-21, which Air Force officials and members of Congress have repeatedly described as a model development and acquisition program that has been very successful at staying on schedule and at cost despite its complexities, there is still a major cost factor to consider.

“As you know … there’s a price to pay for them,” Gen. Allvin told Sen. Rounds, but was unfortunately cut off before he could elaborate.

Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall told members of the Senate Appropriations Committee at a separate hearing last week that the unit cost of the B-21 was dropping after negotiations with Northrop Grumman. However, the Air Force has declined publicly to disclose what the current price tag is for a single one of these bombers, according to Defense News. In 2022, the service said that the expected average unit price for the Raider, based on a total production run of 100 aircraft, was still under a publicly stated target of $550 million in Fiscal Year 2010 dollars. Adjusted for inflation, this is just under $793 million.

Earlier this year, Northrop Grumman also reported a loss of nearly $1.2 billion on the Raider program and said it no longer expected to see a profit across the first five low-rate production lots. It blamed all of this largely on “macroeconomic disruptions,” such as higher-than-expected inflation and other similar economic factors.

Whatever the final unit cost might turn out to be, it is expected to cost the Air Force tens of billions of dollars just to buy all 100 B-21s. This does not include what has been and will be spent on development and other ancillary costs along the way, as well as what it will take to operate and sustain these complicated stealth jets for decades to come. A key tenet of the program was to make the aircraft far more affordable and reliable than the B-2, a jet that was designed 40 years ago, but if that goal materializes, and to what extent, is yet to be seen.

Views about how the Air Force, as well as the other branches of the U.S. military, will wage war in the future are significantly evolving right now. This is all being driven in large part by advances in a number of technological fields, especially regarding uncrewed platforms and artificial and machine learning capabilities. The Air Force, in particular, is also looking at a future where aircraft, especially uncrewed ones, are designed and built in very different ways from how they are now. Reducing developmental timelines and accelerating production capacity are things that are increasingly seen as not just desirable, but as strategic imperatives for success in future major conflicts.

The world in which the requirements for what became of the B-21 were drafted in many ways no longer exists and is still in a particular moment of flux. Right before Sen. Rounds asked Gen. Allvin yesterday about the Raider program, he had questions about the future of the service’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities and capacity. ISR is expected to be among the B-21’s many secondary mission sets.

Allvin said that the Air Force is in the midst of a “transition to a space-air [ISR] mix” and that “that is where the future is.” This is also something The War Zone has been tracking very closely as you can read more about here.

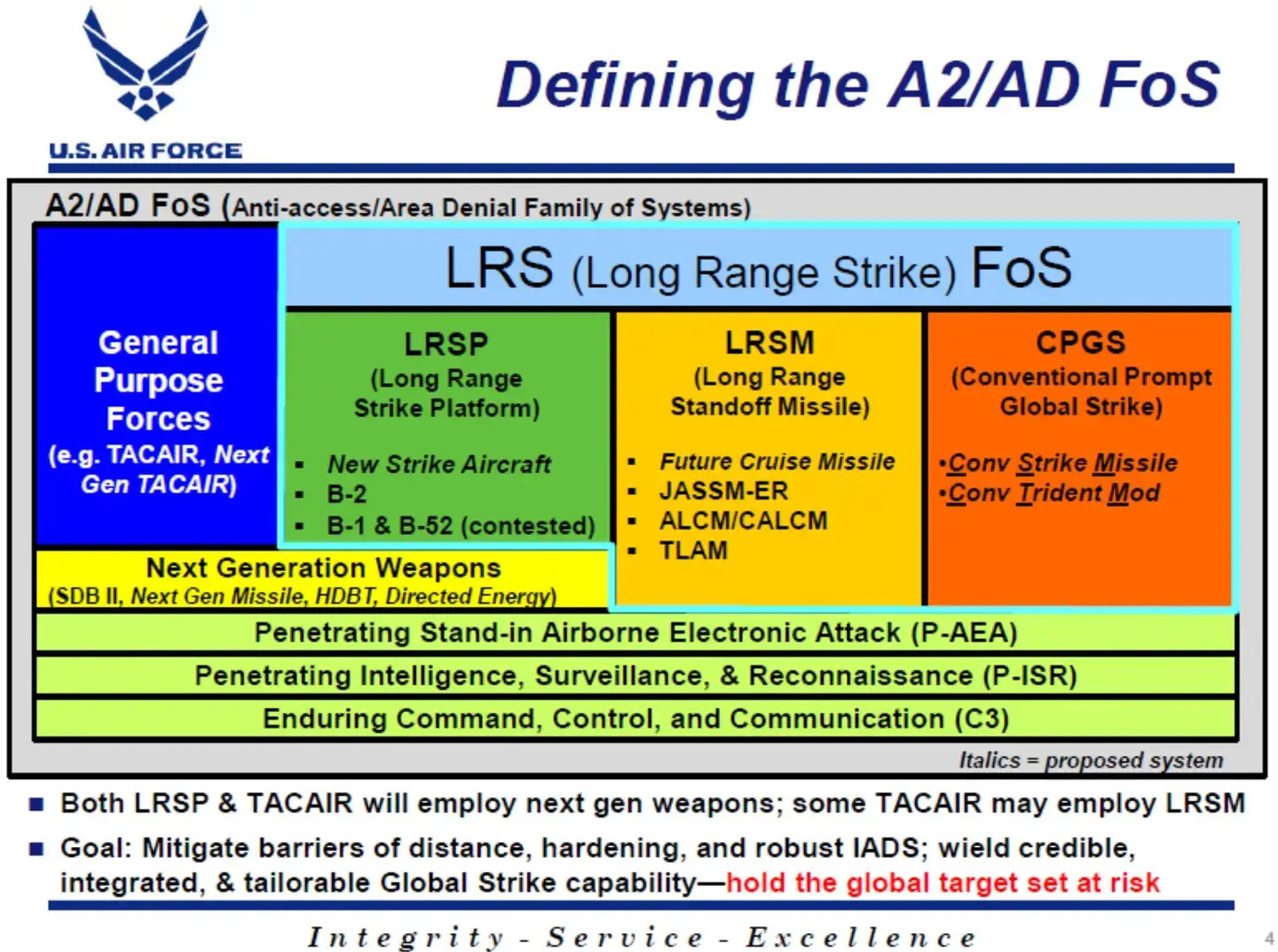

On top of all this, the B-21 is already not really a thing unto itself. The Raider is part of a larger, and still largely classified, Long Range Strike (LRS) family of systems, also now sometimes referred to as the B-21 family. This is something Sen. Rounds specifically noted in his questioning of Allvin yesterday. The Senator’s comment about plans to buy at least 100 examples of the “base platform” also speaks to the possibility of future variants or derivatives of the B-21 within this family.

The AGM-181A Long-Range Stand-Off (LRSO) stealthy nuclear-armed cruise missile is another known member of this system of systems. The Air Force has previously described Penetrating Stand-in Airborne Electronic Attack (P-AEA); Penetrating Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (P-ISR); and Enduring Command, Control, and Communication capabilities as being among the family’s subcomponents. Entirely separate aircraft designs, especially uncrewed ones such as the RQ-180, would be part of this larger family to help support these additional mission sets.

“The B-21 family of systems … involves things that could be carried by or possibly accompany the B-21, things that can support it from off-board,” Secretary Kendall said at a media roundtable on the sidelines of the Air & Space Forces Association’s main annual symposium in September 2023. “That includes munitions, it includes other things that could be used for defensive purposes, for example. So, that’s really what that’s all about.”

Directed energy weapons, which could be used to augment a platform’s defensive capabilities, as well as its offensive ones, have also been mentioned in the past as an element of this family of systems. Other kinds of munitions, as well as other kinds of capabilities, such as advanced sensors, electronic warfare packages, and communications systems (particularly space-based ones), are also likely parts of this larger ecosystem.

“Unfortunately, an awful lot of that is classified,” Kendall said last September.

So, the idea that the USAF would want to lock itself into more B-21s now, or even indicate it is looking to do so, goes against all of these changing trends, from how aircraft are procured to what capabilities they could offer.

The very idea of the ‘bomber’ mission is also changing, as we can see by the B-21’s multi-role capability. But it’s likely to morph even more in the not-so-distant future, driven largely by survivability requirements. Air defense networks are becoming increasingly capable as they are more deeply integrated, fusing information from disparate sensors across the battlespace, including those in space, and leveraging advanced computing and AI to identify targets that would have been very challenging to detect, and especially hard to track, in the past. Counter-air munitions are also becoming longer-ranged and more capable, sporting multi-mode seekers and networking technology. These factors, along with other anti-access capabilities, mean that new ways of executing long-range strategic and tactical strikes may be sought.

This could include hypersonic capabilities, including reusable aircraft, that leverage speed for survivability. They can also keep up with an evolving “kill web” that is becoming geographically larger and far faster at finding and fixing time-sensitive targets than ever before, something a subsonic bomber would be more challenged to do over great distances.

Even suborbital systems could play a major role in what was once the bomber’s mission set in the future. The USAF already wants to militarize SpaceX’s Starship, for instance. On-orbit space-based capabilities will continue to evolve as well, and while the direct weaponization of space remains a taboo subject, it might not be in the years to come as orbital space increasingly becomes another domain of warfare.

There is also the idea of distributed, less expensive, rapidly designed and fielded, and more plentiful platforms taking the place or at least deeply augmenting more exquisite, high-cost ones that are sacked with long development tails. This concept is likely already incorporated as part of the LRS family or it will be in the future, but it could play a far more important role as time goes on.

Finally, we have standoff weapons with increasingly greater range and capabilities that could be seen as requiring a much larger investment due to the battlefield challenges of tomorrow. If even a stealth bomber may have trouble surviving within a couple thousand miles of their targets, then why not launch the weapons themselves much farther away, possibly without a bomber at all? Cost and return on investment are factors, as these weapons are not reusable. But future standoff weapons will be AI-enabled and networked together to work as cooperative swarms, resulting in an overall capability greater than the sum of its parts. With all this in mind, finding the balance between launch platform capabilities and the standoff weapons they fire will be an increasingly challenging task in the years to come.

At the very least, the idea of a bomber will continue to be blurred with each passing year and the need for new versions of this type of weapon, at least in a traditional sense, may evaporate in the decades to come.

So, could the B-21 be the USAF’s last new bomber, at least in a traditional sense? It’s very possible.

Still, none of this rules out the possibility that the Air Force might acquire more than 100 B-21s in the future, and neither did Gen. Allvin in his testimony. There are clear arguments for buying more Raiders, many of which we have highlighted in the past. And these could come in totally new sub-configurations and adaptations of the base platform. Still, just getting to 100 will be a major milestone by itself. The Air Force hasn’t bought bombers of any kind in a quantity like this since the supersonic swing-wing B-1B, the last of which was built in 1988. Raiders are set to replace the Air Force’s B-1Bs, as well as its B-2s.

Even a decade into its development since the contract was awarded, the entire story of the B-21 is still very much being written and much of it remains under a cloak of secrecy. Only time will tell whether the Air Force ends up buying 50 or 150 of these aircraft in the end. Still, the fact that the Air Force is already beginning to think about what might follow the Raider, or at least augment it in the decades to come, is both prudent and logical given the increasingly rapid pace of technological advances and other ever-evolving considerations and matches the deeply transformational age of air combat we are now living in.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com