At the Navy’s League’s Sea Air Space 2017 convention and exhibition, The War Zone learned ATK Orbital believes its Hatchet and Hammer miniature bombs might be a good fit for Lockheed’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighters. The jets sorely need more firepower in their stealthiest configuration, but they still can’t attack fast-moving targets on the ground at all, a key capability for aircraft supporting troops on the ground.

At the core of the issue is the F-35’s on board electro-optical targeting system (EOTS). While the sensor package can detect and track moving objects, it can’t hit them automatically. This is because there is no so-called “laser-lead” function, which would do the math to tell bombs and missiles how far ahead they’d need to fly to actually hit fast-moving land vehicles or boats.

So, as of April 2017, a pilot in one of the U.S. Air Force’s F-35As in their Block 3i configuration has to manually gauge where to point the laser to try and hit a moving target. The Marine Corps’ less advanced Block 2B package lacks any automated functionality, as well. Lockheed and the Pentagon are working to address this issue in the up-coming Block 3F software and hardware, but have suggested the Joint Strike Fighters may not have a full moving-target “laser-lead” capability until the Block 4 upgrades begin to arrive, which is unlikely to occur before 2020, and likely some time after.

Unfortunately, the Pentagon needs more options now. “The ability to hit a moving target is a key capability that we need in current close-air support fight,” Air Force Brigadier General Scott Pleus, in charge of the service’s F-35 integration office, told DefenseNews in February 2017.

Throughout the course of the Joint Strike Fighter project, critics have repeatedly panned the Joint Strike Fighter’s ability to conduct air strikes in support of ground operations in general, often pointing to the much more impressive armament and low-level flying characteristics of the blunt-nosed A-10 Warthog. To try and settle the argument, American legislators have mandated a fly-off between the two aircraft, which Pleus has said is slated to start in 2018.

If the F-35 still lacks the ability to hit tanks and trucks on the move when those tests kick off, it might almost guarantee an embarrassing outcome for the stealthy fighter and reinforce criticisms that the jets are still far from combat ready. The A-10 – as well as fourth generation fighters such as the F-15E Strike Eagle and F-16C Viper – can carry newer targeting pods, including Lockheed’s own Sniper Advanced Targeting Pod (ATP), which have laser-lead capability. In addition, weapons, such as Raytheon’s GBU-49/B Enhanced Paveway II and the company’s still in development Small Diameter Bomb II, have this functionality built into the weapon itself.

So, in February 2017, the Air Force posted a notice on FedBizOpps, the U.S. government’s main contracting website, asking for immediate proposals for a 500-pound class bomb for the F-35 with an integral moving-target capability. This requirement matched the description of the GBU-49/B, which the Pentagon ultimately picked as an interim solution.

At a luncheon briefing at Sea Air Space 2017, Jack Crisler, Lockheed’s Vice President for F-35 Business Development and Strategy Integration, told reporters his company was still having active discussions with the U.S. military on how to quickly add the Enhanced Paveway II to the Joint Strike Fighter’s weapon “menu.” Regardless of if and when the GBU-49/B becomes available for the F-35, it will be the second work-around for EOTS’ long-standing moving target deficiency.

The Pentagon knew at the beginning of the Joint Strike Fighter program that moving targets would pose a problem. When Lockheed subsequently developed EOTS, laser-lead technology was still coming of age. So the initial plan was to arm the jets with advanced cluster bombs to make up for the shortcoming. These Wind-Corrected Munitions Dispenser-Extended Range (WCMD-ER) dispensers, guided by a combination of GPS and inertial navigation system (INS), full of BLU-108/B Sensor Fuzed Munitions (SFMs) would be an interim fix until a more permanent solution came online.

Each SFM consists of four, independent explosively-formed penetrator warheads, which ultimately separate from the main body and fall toward their targets. Each one detonates when its on board dual-mode infrared sensor picks up a vehicle. If it doesn’t find one, it explodes on impact with the ground. A fragmenting ring does give the weapon the ability to kill nearby soft-targets, like people, as well but this system is a far cry from Cold War-era containers full of unreliable hand grenade-sized bomblets. The U.S. military designated the WCMD-ER with 10 BLU-108/Bs as the CBU-105/B Sensor Fuzed Weapon (SFW). You can read all about this weapon here.

But it goes without saying that a cluster bomb intended to strike groups of targets is very different from a missile or bomb outfitted with a unitary warhead intended to focus one individual point of impact. Dropping 10 submunitions to attack terrorists in a lone pickup truck would never have been cost-effective nor uncontroversial. It also wouldn’t have been precise enough to hit specific small vehicles in congested urban areas, which would’ve increased the risk of collateral damage and civilian casualties.

In short, the weapon was always going to be an imperfect solution. Now it’s a moot issue.

On June 19, 2008, then Secretary of Defense Robert Gates declared the United States’ intent to dramatically scale back the use and sale of these cluster bombs. In his memorandum, he cited changing international norms and a moral imperative to protect innocent civilians from unexploded ordnance during and after conflicts.

After 2018, American troops couldn’t use cluster munitions – including bombs and shells – where more than one percent of the submunitions wouldn’t reliably go off. In the interceding decade, regional commanders would have to approve their employment on a case-by-case basis. This appeared largely designed to calm officials on the Korean Peninsula, whose war plans relied heavily on beating back hordes of North Korean armored vehicles with SFMs.

The new rules were a product of an increasingly vocal campaign in favor of the international Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM), which had banned signatories from building, using or exporting weapons that met very specific definitions eight years earlier. CCM did not prohibit members from stockpiling weapons that had fewer than 10 submunitions each weighing less than approximately 8.8 pounds, would detect and engage single targets, and had electronic self-destruct and electronic self-deactivating features.

Though relatively minor modifications would have made the CBU-105 compliant with the CCM, the international stigma against cluster munitions became too much for defense contractor Textron. In September 2016, the firm announced it would no longer make the SFM. This succession of events sent Lockheed and the Pentagon scrambling for another solution to the F-35’s moving target problem.

And this is where Hatchet and Hammer begin to come into the picture.

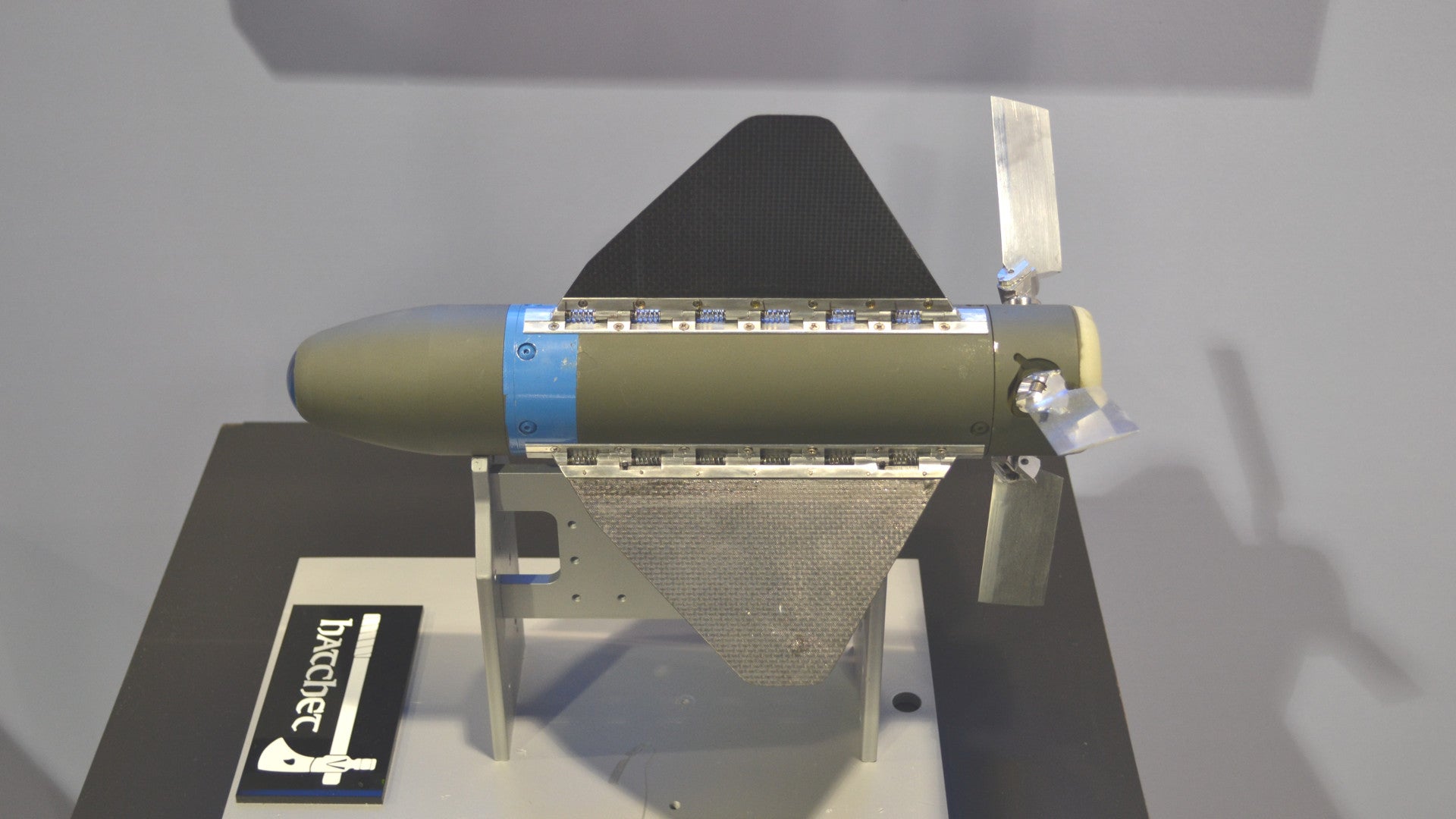

Unveiled in 2012, Hatchet is an approximately eight-pound miniature guided bomb with a three and a half pound blast-fragmentation warhead. Though still in development, ATK Orbital plans to offer the weapons with GPS/INS guidance alone, or a combination of that navigation system and a laser, infrared sensor or even an active-radar homing arrangement akin to European consortium MBDA’s Brimstone, a company representative told The War Zone on the floor of Sea Air Space 2017.

Thanks to advancements in so-called “alternative warhead” technology, it only reportedly takes six of them to saturate an area the size of a football field with deadly fragments. Relying on inert shrapnel rather than bomblets, the Pentagon’s goal with these warheads has been create cluster bomb-like effects without any potential for hazardous unexploded ordnance

ATK Orbital has been working closely with U.S. Special Operations Command on the project, which would be ideal for attacking specific terrorists while reducing unintended casualties. Hatchet and similar designs promise to make a variety of small unmanned aircraft, many of which previously only had the payload capacity to carry out limited surveillance missions, lethal attackers as well.

American special operators would likely employ the weapon from a variety of drones or the multi-mission launcher on newer AC-130 gunships. It is possible a miniature munition such as Hatchet killed Al Qaeda’s number two Abu Khayr al Masri, a son-in-law to the late Osama Bin Laden, in Syria in February 2017.

However, the employee at the booth added that the weapon could be a perfect compliment for the F-35 or other manned fighter jets and ground attack planes. One of the particular benefits of the combination is that the larger aircraft would be able to engage exponentially more targets during one sortie. Rather than just having one 2,000-pound class bomb to drop on one single target, a similarly sized dispenser can potentially carry dozens or even hundreds of the diminutive bombs, each able to strike an independent target or used cooperatively to blanket an area with deadly shrapnel.

The F-35 would only ever have been able to carry two CBU-105/Bs in its flush, internal bomb bay. The jets could’ve carried more on the wings, but would lose much of their stealth advantage in the process. But the ATK Orbital employee explained that the firm had already begun exploring the idea of a setup holding dozens of Hatchets that would attach to the F-35’s bomb bay door specifically, usually reserved for AIM-120 air-to-air missiles. This arrangement would keep the main internal pylon free for other, larger air-to-surface weapons.

One thing Hatchet might not be able to do, no matter what plane drops it, is attack hardened targets or armored vehicles. ATK Orbital says it is working on an elongated, but still small guided bomb called Hammer with a penetrating main charge and a scalable secondary warhead – expected to weigh between three to five pounds depending on the configuration – for at least some of those scenarios.

Still, miniature munitions won’t do anything to fix the core issue with the lack of laser-lead functionality. Until Lockheed makes improvements to EOTS, the tiny bombs will still need a built-in capability to compensate for a target’s speed and direction, or another aircraft, manned or unmanned, or troops on the ground with appropriate equipment capable of providing the laser-lead designation capability will be required. Under such a concept, the F-35s could drop Hatchets, which would sail toward the general target area thanks to its GPS/INS navigation system, where they would begin looking for the laser spot from of one those secondary sources. The U.S. military has already successfully employed the Viper Strike glide-bomb, which uses a similar combination of sensors, to attack moving targets since 2007.

In 2015, Lockheed announced plans for an Advanced EOTS (AEOTS), which would be ready to go as part of the F-35’s Block 4 upgrades in the 2020s. There is no word yet on how much that new system would might cost or what the total bill might be to install it across the existing fleet of F-35s. While it is possible that the company could simply opt to add its Sniper advanced targeting pod to the Joint Strike Fighter as a more immediate solution, Lockheed’s Jack Crisler was insistent that the internal system would be superior to any podded competitor, especially when the jet was in its stealthiest configuration.

The Pentagon and Lockheed both seem to be focused on making sure the self-contained GBU-49/B is compatible for the Joint Strike Fighter first, which would give the aircraft at least one moving target option in the near term. The aircraft aren’t expected to have the necessary software updates to carry and launch the even more capable Small Diameter Bomb II until 2022. In the meantime, both Pentagon and Lockheed have focused the blame for the F-35’s continuing moving target issue on the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

“The U.S., by treaty, is not allowed to use those weapons anymore,” Air Force Lieutenant General Christopher Bogdan complained to reporters in February 2017. “So when that weapon left the inventory, we were left without a weapon that could hit moving targets.”

This, however, wasn’t entirely true. Despite public pressure, the United States has still not formally adopted the CCM. On top of that, despite reports questioning this assertion, Textron repeatedly insisted the CBU-105/B met the one percent requirements outlined of Gates’ 2008 memorandum.

It is possible the Pentagon could have sought out a new manufacturer for the weapons after 2016. However, when it comes to the F-35, a number of foreign partners – notably the United Kingdom – are signed up to the CCM, so the SFW wouldn’t have necessarily been an option for them regardless. But really, as the F-35 timeline slipped, and the ability to hit targets on the move with targeting pods and highly-precise weaponry became the norm, Lockheed and the Pentagon should have known the CBU-105 was no longer viable for that role regardless of the CCM or Gates’ Pentagon memo.

“It’s probably important to know that we had a moving target capability until a treaty kinda took that weapon away from us,” Crisler added during his comments at Sea Air Space 2017, again referring inaccurately to Pentagon policy regarding the CBU-105.

Whatever happens with EOTS, as time goes on, the Air Force, Marine Corps and ultimately the Navy will want add more capability to the F-35 series in general. But Lockheed will have to fix the laser-lead problem to get the most out of weapons such as Hatchet and allow pilots to attack multiple targets, including those on the move, while still maintaining their most stealthy configuration.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com