The U.S. Army thinks a small, tandem-rotor drone could be rushing injured troops from the battlefield to field hospitals in the near future. Dragonfly Pictures, Inc. (DPI) DP-14 Hawk would be the latest way to getting casualties quickly out of harm’s way and into the care of medical professionals.

Since at least 2016, the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s (USAMRMC) Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) has been exploring how pilotless craft might speed up the casualty evacuation process. Though Army officials discussed a number of these developments during a conference at Fort Detrick in Maryland in January 2017, the DP-14 was clearly the star of the show.

“Unmanned and autonomous platforms have the potential to completely rewrite the medical doctrine,” Army Colonel Daniel Kral, head of the TATRC said during the event. Kral explained that drones such as the Hawk could perform a variety of functions, from moving wounded soldiers into areas that might otherwise be too dangerous for existing helicopters or ground ambulances to delivering perishable supplies such as whole blood products.

The DP-14 looks like a miniature version of Boeing’s CH-47 Chinook, the twin-rotor aircraft is 13.5 feet long and two feet wide. It can carry more than 400 pounds of cargo internally at a cruising speed of more than 80 miles per hour for almost 2.5 hours.

The Pennsylvania-based firm offers two side-mounted pods for additional, over-sized items. The company’s website shows Hawks configured to carry water, bales of hay or crop-dusting gear for agricultural work on these external pylons.

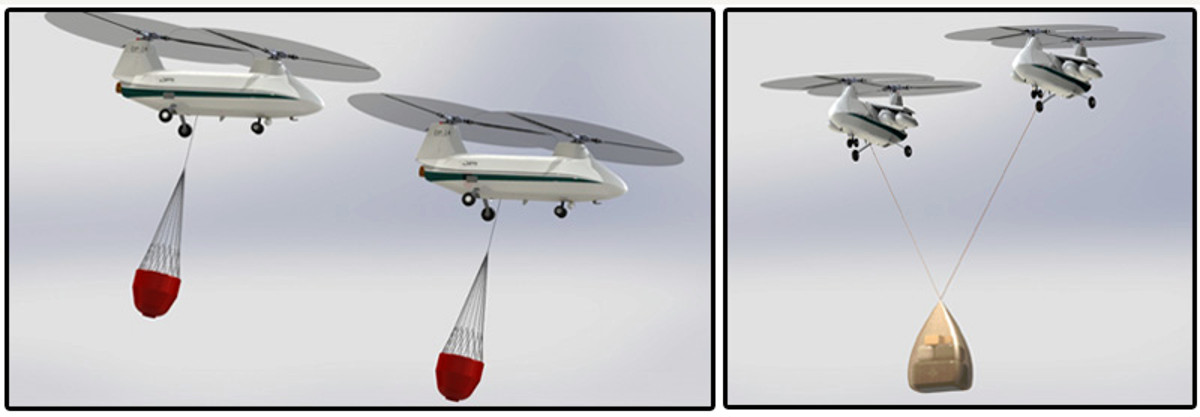

In addition, artwork shows the drones carrying sling loads individually or in pairs. Able to enter a stable hover, the DP-14 can drop its payload within 3 meters of a specified point.

While crews tell the pilotless chopper where to fly, it uses its own on-board computers and 3D laser imaging technology to plot the route and navigate to its destination, according to DPI’s literature. The software is precise enough for the drone to land on uneven terrain or a ship pitching and rolling at sea. It also means the unmanned aircraft can continue to fly even if an enemy force jams or interrupts the GPS signal.

These features could make the DP-14 ideal for rescuing troops in precarious situations. The smaller drones could touch down in relatively tight areas in mountainous, forested or jungle environments where larger medical evacuation helicopters, such as the UH-60 Black Hawk, would never be able to go. The laser-based navigation system could guide the drone through smoke, dust, or bad weather, too.

Though there is no final price estimate for an Army version, DPI’s pilotless rotorcraft would likely be far cheaper than a Black Hawk or other conventional military helicopters. For the price as a single UH-60, the service could presumably buy multiple DP-14s. This fleet could quickly move in to schlep casualties about the battlefield “when dedicated medical evacuation assets are unavailable,” Kral noted.

Of course, the drones wouldn’t necessarily be perfect solution. The small craft have no space for a medic, pararescuemen, or other additional personnel. The Army says a remote monitoring system would allow them to watch a wounded soldier’s vitals in transit, but no one would be able to respond to a significant change in their health.

The DP-14 is slower than most full-size helicopters, too. Depending on how far the wounded individual is from medical attention, it might not be able to get there within the critical “golden hour,” the first hour after a major injury when many treatments have the best chance of success.

Despite its relatively small size, there’s still no guarantee the unmanned helicopter will automatically be able to set down nearby, either. On top of that, just getting an injured individual in and out of the cramped confines of the Hawk might be complicated enough.

And while the DPI says the top-mounted rotor assemblies make it easier to load the drone, the blades would still be spinning at chest or neck height for many individuals. Even if the DP-14’s engines came to a stop after landing, troops would have to be conscious to some degree of what are essentially spinning knives. This isn’t something anyone would want to worry about during a firefight or while struggling to save someone’s life.

At the time of the conference, the Army was still evaluating the DP-14 as part of a project shared project between the TATRC and the Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory. Funding for the ongoing experiment came from the Defense Health Agency Joint Program Committee for Combat Casualty Care.

Even if they’re not perfect for medical evacuation, the DP-14s would be another important tool for commanders on combat. With few changes, the drones could move other personnel and supplies in support of various missions, including special operations and covert activities, as well.

This is hardly the first time the U.S. military and foreign armed forces have looked at new aviation technology, especially developments in vertical lift, to improve casualty care and reduce combat fatalities, as well as transport cargo and personnel discreetly. During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces and U.K. Royal Air Force (RAF) developed numerous pods and sacks to strap onto fighter aircraft. Depending on the mission, these systems could carry both casualties and early special operators. Axis air arms performed similar tests.

The Army went so far as to develop a “Man Pick-Up Kit” that could scoop troops or down aviators off the ground without a the rescue plane even having to land. This concept later evolved into the Cold War-era Fulton Recovery System, also known as the Skyhook, a notable feature in the 1965 James Bond movie Thunderball.

This improved device involved a harness tethered to a balloon. The individual on the ground would inflate the balloon, extending the line into the air. An aircraft equipped with a special v-shaped hook on the nose would catch it and yank whoever was attached into the air. The crew would then real them into the back of the airplane.

The U.S. Air Force and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) deployed the system primarily to recover special operations forces and secret agents from behind enemy lines, though it had the potential to rescue personnel stuck in dangerous situations.

In 1962, during Operation Coldfeet, the CIA used the gear on a modified B-17 bomber to recover American military intelligence officials from an ice flow where they had been inspecting an abandoned Soviet research station in the Arctic. In 1996, the Air Force retired the last of the Fulton Recovery Systems.

But this was hardly the most unusual rescue project to come out of Cold War experiments. The major U.S. services tested inflatable miniature planes, jet packs and powered and towed hang gliders, among others.

Starting in the Korean War, ever improving helicopters became a much more viable method of getting casualties from combat zones for life-saving treatment. The DP-14’s side-mounted pods do look very similar to the stretcher racks on Bell’s iconic 1950s-era Model 47 helicopters, which became even more famous thanks to the television show M*A*S*H.

Similar experiments continued well after the Soviet Union collapsed. In the late 1990s, British company AVPRO cooked up under-wing pods for combat jets and gunship helicopters, such as the Harrier jump jet or Apache attack helicopter. Later promotional literature even showed the contains underneath the wings of Lockheed’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. As before, the firm expected its Extraction/Insertion (EXINT) unit could hold any sort of passenger, from casualties to elite troops.

“It wasn’t just a hairbrained scheme thought up by some mad professor,” the ThinkDefence blog’s detailed review of the project explains. “[This was] a direct result of operational experience in the Gulf and Balkans conflicts.”

On June 2, 1995, Bosnian Serb forces shot down an Air Force F-16 fighter during Operation Deny Flight. Captain Scott O’Grady survived the incident, but spent six days hiding from a local population he believed to be hostile, as well as ethnic Serb militias, before linking up with a U.S. Marine Corps rescue force.

Nearly three years later, Serbian troops hit an F-117 stealth fighter during Operation Allied Force. Air Force rescuers picked up the pilot, Lieutenant Colonel Dale Zenko, within hours of his crash.

In 2009, four members of the U.K. Royal Marines famously rode to safety in Afghanistan while strapped onto the sides of RAF Apaches. Images later emerged of American Marines performing a similar maneuver with their AH-1 Cobra gunships.

A drone medical evacuation aircraft is a logical response to these concerns and subsequent developments. Downed pilots or wounded troops effectively trapped behind enemy lines are exactly the kind of situations where an unmanned rescuer, less conspicuous and a smaller target than a large chopper, might be especially useful.

The DP-14 isn’t the first experiment with an unmanned aircraft in the vertical lift role, either. The rapidly expanding international markets for both drones and vertical take-off and landing aircraft mean there is no shortage of contenders for flying air ambulances.

DPI’s offering is similar in size and scope to Mist Mobility Integrated Systems Technology’s Snowgoose GPS-guided paramotor. With a top-speed of approximately 40 miles per hour, the unmanned pod could travel nearly 200 miles depending on how much cargo it had crammed inside.

In 2005, U.S. Special Operations Command began buying a number of Snowgoose systems, with the designation CQ-10A. The drone’s main limitation was the need for a speeding truck to get it up to speed and into the air. An improved CQ-10B model used the same basic shape, but employed a gyrocopter design, which allowed the unmanned cargo-hauler to get off the ground by itself.

But small might not be exactly what the Army necessarily wants. In August 2016, the service wrapped up a demonstration of the larger Lockheed Martin K-Max helicopter casualty evacuation role. The K-Max can operate with and without a pilot. Between December 2011 and May 2012, the Marine Corps explored using a K-Max drone to deliver cargo in Afghanistan. As part of the Future Vertical Lift program, the Army plans to eventually phase out all of its existing helicopters, something that could help pave the way for new capabilities like the DPI Hawk or a larger drone.

Separately from the Army, the Navy and Marines are working on an autonomous drone version of the venerable UH-1 Huey helicopter for both cargo-carrying and casualty evacuation duties. Like the DP-14, the Tactical Autonomous Aerial Logistics System (TALOS) uses a laser-enable terrain-following system to get to and from the target area safely. Contractor Aurora Flight Services demonstrated the navigation gear on an Ex-Army UH-1H in February 2017.

On the commercial side, in January 2016, Israel’s Urban Aeronautics completed the first untethered test flight of its AirMule. The company pitched the boxy “flying truck” as both a military and civilian tool, potentially replacing various traditional cargo and passenger carrying vehicles. In March 2017, European aviation giant Airbus unveiled an airmobile concept car.

“The growing planned use of unmanned systems and robotics on the future battlefield affords both great opportunities for medical force multipliers,” Gary R. Gilbert, in charge of TATRC’s Medical Intelligent Systems program, said at the Fort Detrick conference. “We are already conducting research in how to use these unmanned systems to support medical missions.”

In short, there are a lot of options beyond the DP-14, but a pilotless rescuer – or unmanned commando transport – of some description could definitely be part of the Army’s near future.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com