From the very beginning of the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine nearly three weeks ago, there have been persistent fears that Russian forces might attempt to capture the strategic Black Sea port of Odesa. Indications that a flotilla of Russian warships, including large landing ships, has taken up positions offshore, together with Ukrainian authorities saying that dozens of missiles hit targets in and around the city just tonight, have prompted new concerns that some kind of ground assault may come sooner rather than later. Ukrainian officials have already taken a number of prudent steps to fortify the city against amphibious landings and other attacks. But should invasion come, it is Odesa’s vast and ancient catacombs deep below the city that could prove particularly vexing for Russian invaders.

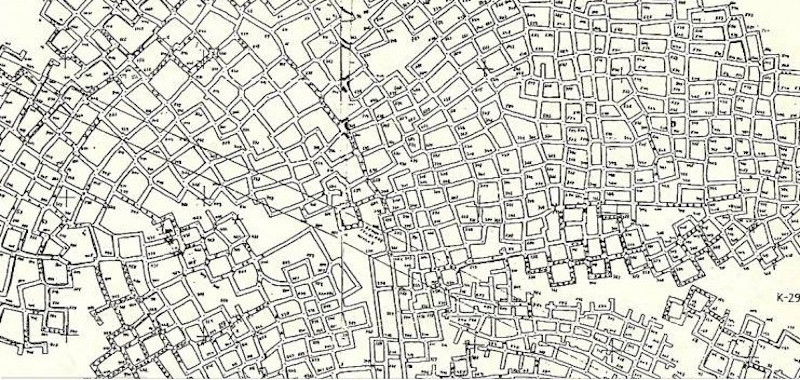

Officially, the Odesa Catacombs comprise at least 2,500 kilometers, or just over 1,550 miles, of generally interlinked tunnels running under the city, as well as into outlying areas. Portions of the Catacombs are known to exist at three different depths at least, with the deepest being 60 meters, or almost 197 feet, below sea level, and there are at least 1,000 documented entry points. It is one of the world’s largest known underground networks.

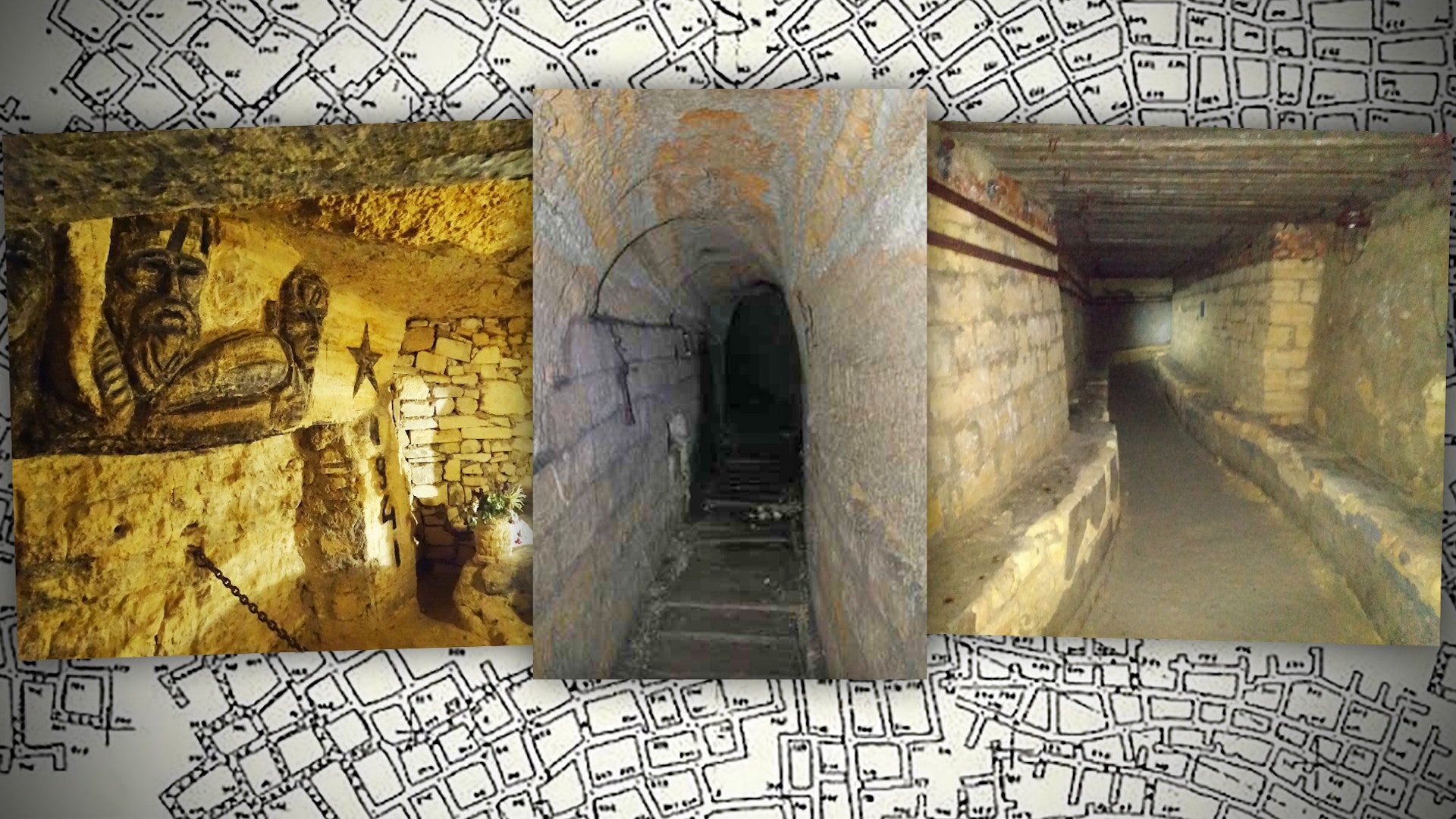

When construction of the first tunnels under Odesa began is not entirely clear, but they may date back to the 17th Century. Artwork can be seen on the walls of some parts of the Catacombs that is at least from the 19th Century. Their existence is largely linked to the demand for coquina, a kind of limestone that is made up in significant part by fossiled invertebrate shells. Coquina extracted from these underground quarries was key to the growth of the city prior to the 20th Century and was entirely unregulated, which helps account for the extent of resulting Catacombs.

Soviet authorities curtailed the extraction of coquina from underneath Odesa after the 1917 Revolution, but the Catacombs remained a fixture in Odesa. Smugglers and other criminal elements, who had already made use of the labyrinth over the years, continued to do so. During the ensuing Russian Civil War, civilians hid in the tunnels from the fighting, and it seems more likely than not that the tunnels had been used in this way before then, as well.

The catacombs continued to provide shelter for civilians during World War II. They gained more notoriety during that conflict for their use, in part, as a base of operations for Soviet partisans fighting Nazi forces in the region. In 1969, a Museum of Partisan Glory was established in a part of the Catacombs Nerubayske, a village some six miles northwest of the center of Odesa, to commemorate this period, and the activities of partisans under the command of Vladimir Molodtsov-Badaev, an official Hero of the Soviet Union, in particular.

The partisan museum was the only part of the Catacombs officially open to the public during the Soviet era, which continued to be the case after Odesa became part of independent Ukraine following the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, there remains plans to use the tunnels in case of attacks, including during a nuclear war.

There are remnants of activity, past and present, spread throughout the Catacombs. This includes old mining infrastructure, such as reinforced walls and tracks for minecarts. Weapons and other items that belonged to partisan forces, among other things, are still sometimes found in less explored areas.

With Ukraine now again at war and the threats to Odesa being very real, the Catacombs may well take on these roles again. In a video posted on YouTube on March 12, The Washington Post interviewed individuals in the city who have at least been preparing portions of the tunnels to be used as shelters that civilians can hide in from attacks.

“I think we could accommodate around 300 people,” Aleksandr Sadovnikov, one of the individuals who has been helping to organize the shelter, told The Washington Post. “At any rate, the nearby houses would easily fit in here.”

“Of course, we have three floors of ground above us,” he added. “I don’t know what kind of projectile could penetrate this layer.”

It’s not clear whether any other portions of the Catacombs may be in the process of being converted into temporary shelters or if there are plans to make use of other sections for more active military purposes. There are certainly serious questions about the real utility of the underground network in the latter case. During World War II, the Nazis and their fascist allies sealed many entrance points deliberately in an attempt to either squeeze partisans out of the tunnels or entomb them. Many of those irregulars, including Molodtsov-Badaev himself, did not survive the conflict.

In 1995, a group set the record for the longest trek through these tunnels, which lasted 27 hours and saw them explore approximately 40 kilometers, or almost 25 miles, worth of the Catacombs. The network remains largely unmapped to this day and nature has conspired over the years to block access at many points.

“On a few occasions we found our path blocked altogether; where brittle layers of sandy rock had collapsed to form impenetrable walls ahead,” writer and photographer Darmon Richter recounted on his website Ex Utopia back in 2013 after taking a tour of a less touristy area of the Catacombs. “I was alarmed to discover that even some paths once familiar to my guides were now impassable – these cave-ins were both recent and regular.”

The labyrinth-like nature of these tunnels, combined with these routine cave-ins and flooding, can certainly make them dangerous and have long given rise to stories about people getting lost and dying in the Catacombs. At the same time, many of these stories may well be urban legends.

Some sections of these tunnels could still provide valuable cover, as well as routes for Ukrainian forces to move unobserved and protected from enemy fire, especially inside Odesa in the event that Russian forces move into the city. Points of entry could provide firing positions for friendly forces, who could then quickly retire back into the tunnels and relocate somewhere else. Any parts of the Catacombs that are robust enough to serve as bomb shelters might also be usable by military personnel as temporary living quarters. Even less livable areas could be used as weapons caches.

These potential benefits could fit well with the more traditional efforts that have been taken to fortify the city from attacks, including the erection of barricades and checkpoints, guarded in some cases by volunteer forces, and the placement of tank traps on key streets. Local authorities have covered a number of historic monuments with sandbags, hoping to protect them from what could be grueling street fighting, as has already emerged elsewhere in Ukraine.

At least some of Odesa’s beaches, typically major tourist spots, have been mined. Pictures have shown tanks in positions near the water’s edge to be able to fire on any Russian units that may attempt to conduct amphibious landings.

When Russian forces will ultimately launch a major offensive targeting Odesa, which the Catacombs and these other defenses could come into play, remains to be seen. Satellite imagery taken just today shows was is almost certainly a flotilla of 14 Russian warships, including amphibious warfare vessels, heading in the general direction of the city.

In addition, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense has said that 90 missiles were fired at targets in and around Odesa tonight in what could very well be a prelude to an amphibious operation. Video footage had emerged on social media last night that appeared to show anti-aircraft batteries near Odesa attempting to intercept something incoming threats of some kind, as well.

Earlier today, a senior U.S. defense official today acknowledged the apparent Russian maritime activity near Odesa, but they said that there were no indications of any imminent amphibious landings. This would, of course, not preclude such an operation in the coming days following a sustained bombardment.

In addition, other Russian forces may be attempting to advance toward the Black Sea port city overland via the city of Mykolaiv to the east. The progress of those units, or lack thereof, might have an impact on how the Kremlin eventually decides to proceed.

No matter what, Ukrainian forces in Odesa, and the city’s residents, have already been bracing for an assault of some kind for weeks now. It only looks increasingly likely now that the famous Catacombs will soon again provide shelter, and possibly much more, this time from invading Russian forces.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com