The U.S. Navy’s damaged nuclear fast-attack submarine USS Connecticut (SSN-22) made a secretive journey from Guam to San Diego over the last few weeks, with the submarine arriving unannounced in San Diego harbor on the morning of Dec. 12, 2021. The voyage was likely incredibly uncomfortable and fraught with danger. To give us a better idea of the risks involved and what this ordeal would have been like for Connecticut’s crew, we talked to our friend and veteran submariner Aaron Amick who spent 20 years on submarines as a Sonarman and now runs the excellent website Sub Brief that covers all matters regarding submarines and naval warfare.

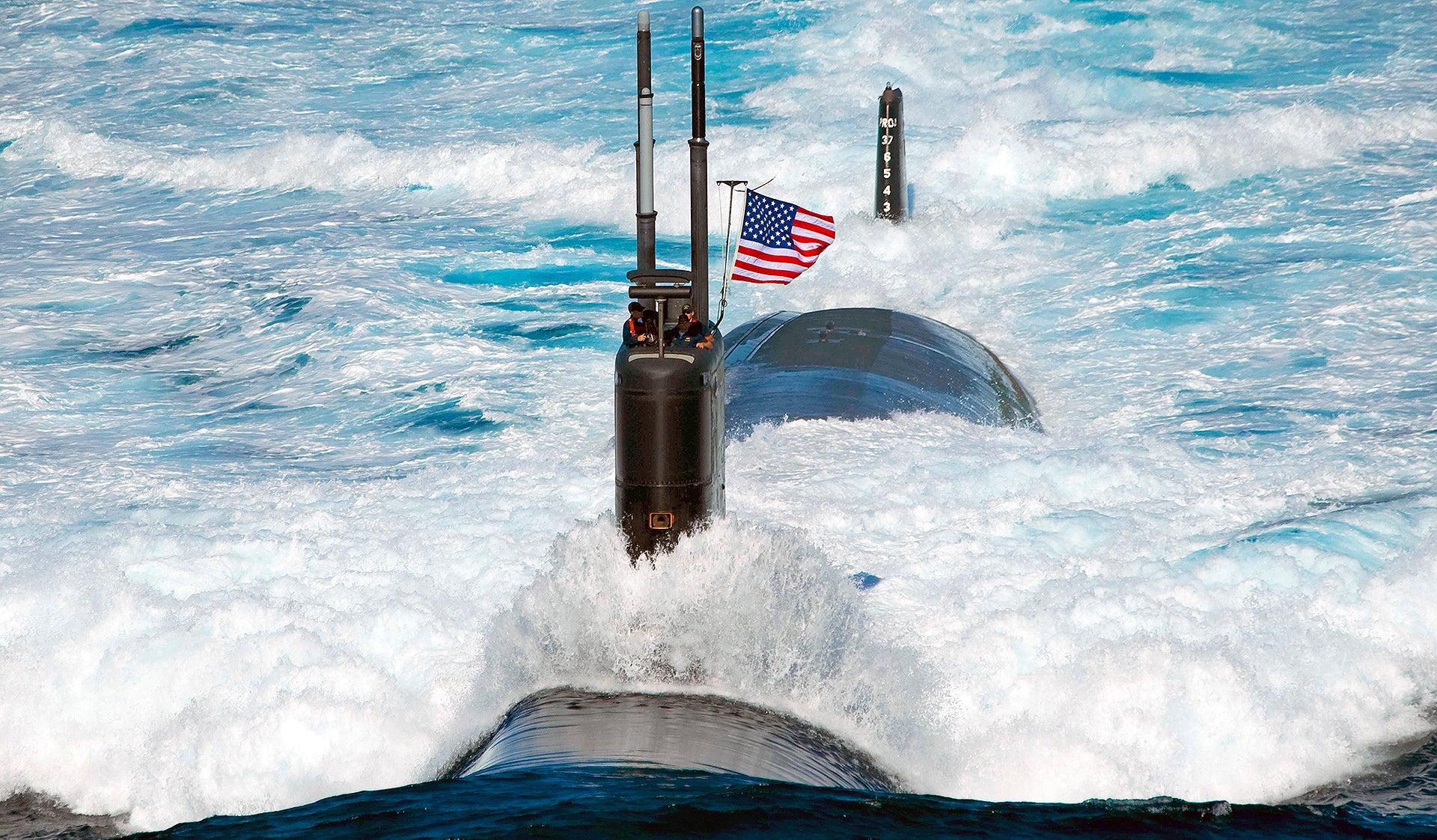

A little background first. The Seawolf class submarine, of which there are only three in existence, slammed into an underwater seamount on Oct. 2, 2021, in the South China Sea and subsequently limped its way to Guam where the damage was assessed. While the full extent of the damage is unknown, the boat’s entire forward sonar dome was ripped off as a result of the impact. Connecticut will now need major repairs, likely spending years in dry dock, in order to return to sea, if indeed she is able to do so. Still, just getting her to a place where she can receive this level of attention was a major undertaking, with the stricken sub traveling over 6,000 miles in what would have been a marathon in endurance for her crew, the leadership of which was quickly replaced following the accident.

So with that background in mind, here is our exchange:

Considering what we know about Connecticut’s collision and damage, one would think it would not be able to safely dive and it would have made the trip from Guam to California on the surface. Is this your assessment as well?

Yes. I think they transited on the surface, with at least one support vessel, at an average speed of 10 knots.

What is it like traveling in a submarine while it is surfaced? What does it feel like in different sea conditions?

A submarine on the surface is constantly rolling side-to-side even in the calmest of seas. It would have induced ‘sea sickness’ to those susceptible. If the rolls were large enough, it would have been tough to move or even sleep in a bunk. Most bunks have a towel rack, I have had to hook my forearm into it to help keep from being tossed out onto the deck in rough seas.

The lack of sleep, or what little sleep the sailors got, probably led to a lot of fatigue after the first few days of the over 20-day journey. Feeling seasick and exhausted is not ideal for watchstanding. It’s likely they implemented a flexible or augmented watch rotation for anyone who could not complete their watch.

The watches are reduced during surface transits. For instance, you don’t need a diving officer. Watches in Sonar and other stations operate at reduced staff. In fact, on the surface, sonar is pretty useless and Connecticut’s bow sonar array is totally useless in its current state. The Seawolf class has other sonar arrays along its flank that may still operate. They may have chosen to man those systems, but on the surface, radar is probably the primary sensor for contact management. So it’s possible some crew were flown to the states and there was a reduced ‘skeleton’ crew onboard during the transit.

That being said, because of the damage to Connecticut, there were probably additional watchstanders monitoring the forward bulkhead of the pressure hull and any hull penetrations below the waterline.

The ride is already pretty bad with the dome on. I imagine it was a very wild ride for the crew considering the damage. I expect everyone was exhausted when they reached San Diego.

What are the general risks associated with traveling on the surface?

Collision is the largest peacetime risk while on the surface. Submarines are not as fast and less maneuverable than their surface ship counterparts. This requires officers to think ahead and plan maneuvers to avoid close contacts.

Bridge watchstander safety is also a concern. A watchstander in the bridge can fall overboard and weather can cause everything from heat exhaustion to frostbite. Bridge watchstanding with sick and fatigued sailors can lead to disaster.

In this case, there would be at least one officer and one enlisted lookout on the bridge [atop the submarine’s sail]. If things got busy, they may add an additional phone talker to manage communications below decks, but that is only in extreme situations like when there are a high number of close contacts near shore.

What about in a situation when the boat cannot dive at all?

Voyage planning is a large part of transiting a damaged submarine that can’t dive. Weather, specifically sea state, would play a role in the route from Guam to the West Coast of the United States. They may have had to go around some foul storms.

For ventilation, they probably had the hatch to the bridge open at all times. If that’s the case, rain would have easily gotten inside the submarine. This would require frequent attention to prevent it from pooling.

One would think traveling at slow speed due to the damage done to Connecticut and not being able to dive would make for an arduous journey that would last at least over 6,000 miles. What do you think the journey was like for the crew?

I think the journey was tedious, exhausting, and miserable for everyone onboard. For anyone who was seasick, it was a nightmare voyage.

What about the preparations for such a journey?

They would have briefed the journey in detail before going underway. Plotted a route, got water space from squadron (water space is deconfliction much like ‘airspace.’ Imagine if squadron is part of an air traffic control network across the globe) and coordinated with an escort support vessel. Weather probably played a large role as to when they left and how they transited across the Pacific.

I think they would have had a lot of easy-to-prepare meals. Maybe even MRE’s in case they could not cook in high sea states. It’s common to serve ‘cold cuts’ on the surface if the cooks can’t keep the food on the grill. Cold Cuts are just pre-sliced processed meats and cheese with sliced bread.

She must have had escorts. What do you think a proper package of assets would be to see she got back to the continental United States safe?

I would expect, at a minimum, there should have been an armed escort to provide additional security, sensor, and communication support. Maritime aviation should have been part of the escort, but not a necessity.

Preferably, a submarine support and rescue vessel should have sailed near her the entire trip. I don’t know if one was available or in Guam, so it is possible that didn’t happen.

Based on the very limited information we have at this time, do you think USS Connecticut will be able to be returned to service?

This is purely speculative on my part, but if there is no significant damage to the prime mover (power train), I think she will return to service after a lengthy drydock and recertification period.

I am very proud of the officers and crew who managed this trans-Pacific trip in a damaged submarine. It was very risky and could have ended with the loss of the vessel. Their professionalism and determination brought USS Connecticut home and that is quite an accomplishment.

UPDATE:

We now have footage showing just how rough a ride it is even in relatively calm coastal seas for Connecticut as it left San Diego on December 15th, 2021. You can check out that video and the update on its voyage here.

Author’s note: A big thank you to Aaron Amick for sharing his thoughts with us and to our friends CRJ1321 and Warshipcam for their great photos and coverage of the USS Connecticut’s arrival in San Diego.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com