The twin-turboprop, twin-boom OV-10 Bronco is one of those rare aircraft that seems to never cease being of interest. Not only does nothing much else look quite like it, but this counterinsurgency specialist has enjoyed a truly unusual career trajectory, which has taken it from the jungles of Vietnam, via Operation Desert Storm, to hunting ISIS insurgents in Iraq. In the meantime, it’s also seen combat in some lesser-known conflicts, from confronting guerrillas in the Philippines to taking part in a coup d’état in Venezuela. Today, its unique flying qualities and capabilities mean it’s in demand for training Joint Terminal Air Controllers (JTACs), more widely known as Forward Air Controllers.

But what was it actually like to fly the Bronco as a frontline combat aircraft during its tenure with the U.S. Air Force? Unlike its more glamorous fast-jet brethren, the OV-10’s Air Force career is little known and rarely publicized. One man who can help set that record straight is ‘Danno,’ who spent his last two Air Force assignments strapped in the cockpit of the Bronco.

Over to you, ‘Danno’…

The War Zone’s Tyler Rogoway asked me a couple of years ago when he noticed I had some military flying experience if I might have some stories to contribute. I more or less blew him off, as I value privacy and don’t normally toot my own horn. But I’m getting old now, and my kinfolk don’t give a crap about what I did, so I’ve changed my mind, and thought I’d share a couple of stories that might be of interest to the readers here since they are about a favorite topic: war machines.

I ultimately accumulated 810 hours in the OV-10 during my two tours at the 27th Tactical Air Support Squadron (TASS) at George Air Force Base, California, and the 19th TASS at Osan in South Korea. That total includes about 50 hours in the Thai OV-10C model (the U.S. Air Force model was the OV-10A).

My whole time flying OV-10s (and my earlier F-4 Phantom II assignments) was peacetime simulated combat. I had previous-enlisted time prior to 1971 (not in Vietnam) and that counted towards my 20-years of active duty. I got my wings in 1974 and retired in December 1989, and there were no major wars in that period. President Ronald Reagan managed to get us into a few small conflicts (Beirut, Grenada, and Panama) but I didn’t participate. My stories are not about war. There are several good Vietnam-era books that tell stories of brave Forward Air Controllers in OV-10s (as well as O-1 and O-2 aircraft) during that war. In the meantime, I’ll just temporarily call this forum the ‘Cold War Zone.’

Having said that, I did shoot a lot of 2.75-inch marking rockets (usually with a white phosphorus warhead, dubbed ‘Willy Pete’) and dropped a lot of 25-pound practice bombs (BDU-33s; they had a small smoke charge) from the Bronco. We used the small practice bombs to mark targets on ranges when the Air Force said we were getting short on Willy Pete. The only time I fired the M60 machine guns was when I flew the Thai C-models. They had left the guns in the aircraft, while the USAF had taken them out.

This is a short story about a Military Training Team (MTT) I led in Thailand to instruct a few Royal Thai Air Force (RTAF) OV-10C squadron pilots in the art of Forward Air Control. This took place in February and March 1987.

In 1986, I checked out in OV-10s after several years as an F-4G (Advanced Wild Weasel) pilot. The Bronco wasn’t my first choice in a change of weapons systems, but, you know, the needs of the Air Force came first, and I became mildly excited about flying it during peacetime. It would definitely be a change of pace, because flying Weasel tactics during the early 1980s was mainly done at 500 feet (or lower) and the speed of heat. Seeing what was on the ground in the Phantom at those speeds was blurry — unless you were pointing at the ground and a target. Identifying details on the ground was something I thought would be fun.

The OV-10A squadron (27th TASS) to which I was assigned needed experienced fighter pilots (at least that is what the assignment people said). This was a large Bronco squadron with over 40 airframes and a shitload of pilots. The Air Force had recently deactivated two OV-10 squadrons at Sembach in West Germany, and they were all brought to George AFB. Over half the pilots were what we called ‘FAFACs’ (First Assignment Forward Air Controllers). They were pilots out of UPT (Undergraduate Pilot Training), and the Bronco is what they were awarded, with the likely follow-on assignment in a fighter.

Most of these guys were first lieutenants and wet behind the ears.

FAFACs were flying the Bronco more or less to keep their flying skills up to speed and learn the tactical environment. Their primary job was acting as Battalion Air Liaison Officers (ALOs) with the U.S. Army. At least twice a year, they would go on temporary duty (TDY) to their assigned unit with the Army on exercises and camp out in tents and drive around in Humvees or armored personnel carriers, and coordinate air support for the battalions. If war broke out, that was their job, while us more experienced and higher-ranking officers would be tasked to fly the OV-10s as FACs. I never had to eat MREs as I (deservedly) fell into the latter category.

After about eight months of being a flight commander, I was made chief of STANEVAL (standardization and evaluation) and was in charge of four or five other evaluators. We gave all the check rides to the squadron pilots.

A month into this job, the squadron commander (an O-6) called me in and asked if I wanted to head an MTT for about a month in Thailand. The RTAF had two squadrons of OV-10Cs and had requested some FAC training, as they were a little unsure about how it worked. They were primarily using their Broncos for counterinsurgency and were worried about FAC tasking in a Cobra Gold exercise that included U.S. fighters. I didn’t hesitate in volunteering as I had been to Thailand several times during my stint flying F-4s at Clark Air Base, Philippines, and I loved the place, especially the food and, uh, other things.

The team was three pilots, one other guy from my squadron and one pilot (who would meet us in Bangkok) from the OV-10 squadron at Wheeler Air Force Base in Hawaii. We learned the Thai squadron we would be working with was based in Chiang Mai. To those who are familiar with the country, you know that is a ‘sweet’ northern city with much cooler temperatures with great sightseeing and plenty of after-hours activities.

Before leaving, my squadron mate and I prepared a training syllabus that included classroom lectures and flying training missions. We were told by the gurus at TAC HQ at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia, that there weren’t going to be any live weapon deliveries (marking rockets) because range space/time was limited there. All flying training was going to be what we called ‘dry CAS’ [close air support].

We packed up our harnesses, G-suits, helmets, clipboards, etc., and headed to Thailand from California. We had a free day in Bangkok, so I reacquainted myself with Patpong and Soi Cowboy (Google it).

I’ll not bore you with the details of our reception and classroom instruction except to say it went very well. It was obvious to us they had picked their best English speakers among the five or six pilots to be trained. Even then, Thai English can be a little hard to understand if you’re not used to it, so it was a minor problem.

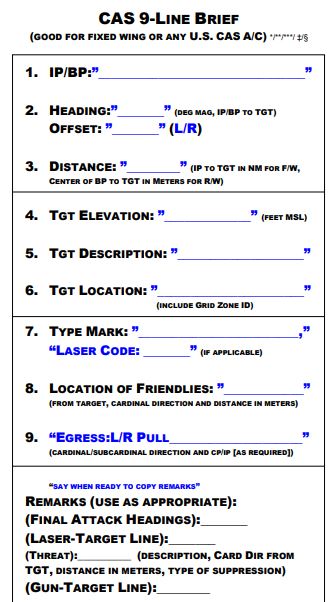

We finally started flying with them, as instructors in the back seat. Basic FAC tactics include what is called a nine-line brief to the fighters you are working with. On a couple of training sorties, we actually had RTAF F-5Es fly up from Korat to do the dry CAS. On the other flights, the squadron’s other OV-10s simulated the fighters. We soon figured out that we had to simplify the nine-line brief.

We decided to use low-threat tactics, talk the fighters to the target area, put them in a wheel above us, then give them items four to eight. Since it was all dry, our most-used simulated targets were a village or town Buddhist temple. These buildings stood out with gold or orange roofs and were easy to talk the fighter pilot’s eyes onto as the target.

I tried to use bridges and river banks several times and that was hit or miss with the simulated fighter guys who couldn’t get their eyes on the target. Maybe it was a language problem but our inability to mark the targets with a Willy Pete added to the difficulties. I later asked the U.S. Assistant Air Attaché at the embassy in Bangkok if we should have been dry dive-bombing temples and he didn’t think it was a good idea. But he was a former C-141 pilot. What the hell did he know?

The Thai pilots couldn’t care less.

The Thai OV-10C was almost identical to the OV-10A we flew back at home, with minor cockpit differences. The main one, I remember, is they didn’t have a fire-suppression agent for the engines in case of an engine fire. Performance between the two models was identical; that is, very good performance with two engines running but lousy performance if you lost one. Fortunately, that never occurred during our TDY. As previously mentioned, the Thais also left the four M60 machine guns in the sponsons while the USAF had them all removed.

The training was progressing as expected when one morning, about two weeks into the MTT, the Thai squadron commander informed us that a car was waiting to take us to the U.S. Consulate in Chiang Mai. We didn’t even know a U.S. Consulate existed there. We arrived and were ushered into an office where a balding gray-haired guy in a white shirt, with glasses, was standing beneath a rotating ceiling fan. He introduced himself at the U.S. Consulate General. Standing to his side was some Caucasian dude in an Aloha shirt with sunglasses on, although it wasn’t particularly bright in the room. I immediately thought of a 1960s movie scene out of The Ugly American.

The Consulate General introduced the shades guy as Agent “John Smith” from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). We were offered water and invited to sit down. They then began their briefing.

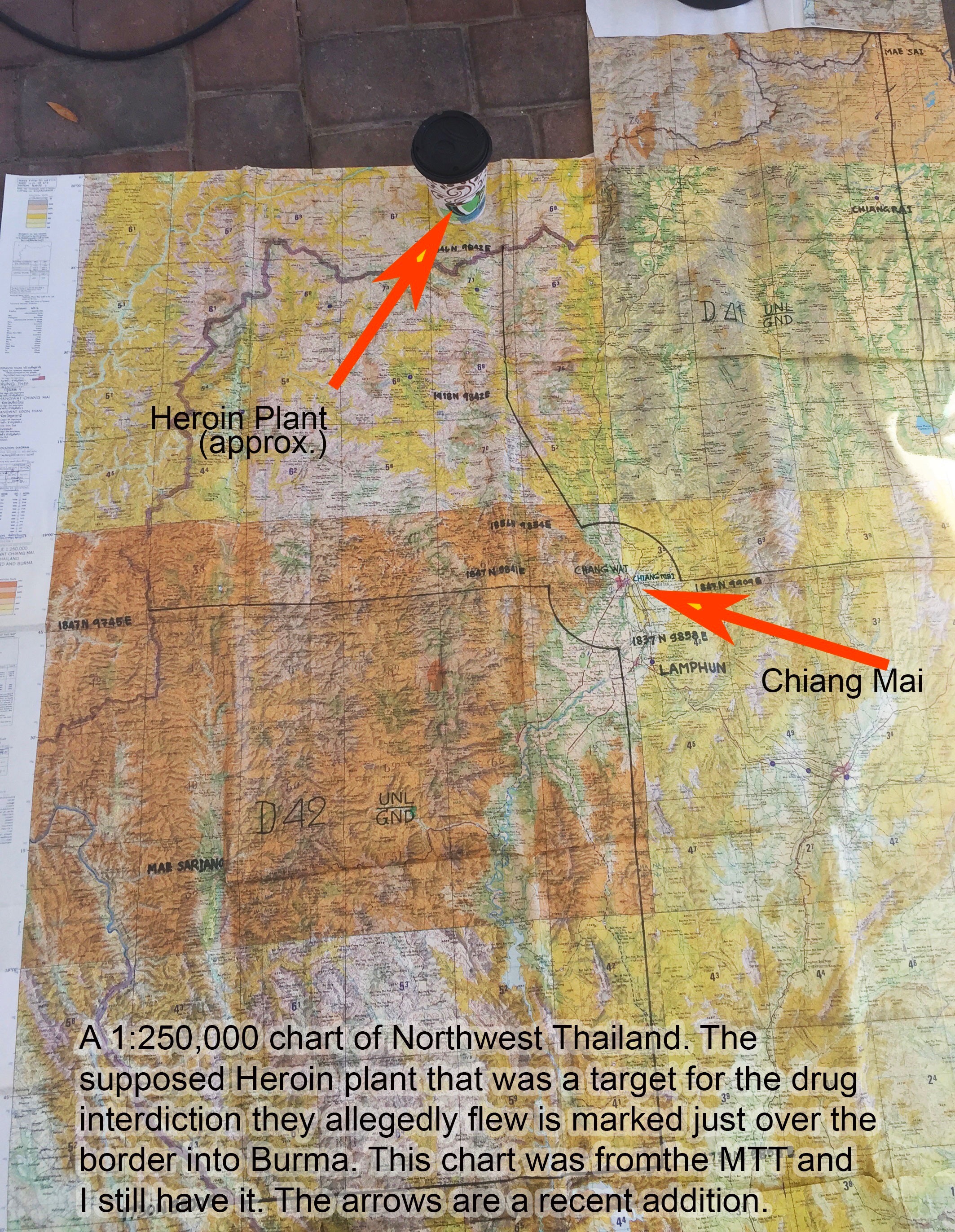

Some background info might help: In 1986, Reagan had declared war on drugs, and the primary focus was on the Colombian cartels. But the Golden Triangle area just north of Chiang Mai still produced the hard drugs from poppies that we know as opium and heroin. The Thai government was getting enormous pressure from the United States to do something about the drug traffic from that area.

The DEA guy told us Chiang Mai was the home of a couple of drug lords who were involved in most of the heroin traffic from the Golden Triangle. He said that, because we three were the only U.S. military guys in the whole damn city working with the RTAF, we had to leave town for a few days because our lives could be at risk. That got our attention, and I asked why. He reluctantly told us the Thai OV-10 squadron, which was our host, was going to conduct a drug interdiction mission that might involve casualties. Depending on how the mission was executed, the drug lords residing in Chiang Mai may think that our presence at the squadron would indicate our involvement somehow, even though we were strictly doing CAS training.

After hearing that, we readily accepted the offer of flying (commercially) back to Bangkok for a few days. “Where are the flight tickets, and what five-star hotel did you book us in?” was an immediate question. Naturally, we wished for more detail on the operation, but at this point, we knew the Thai pilots quite well, and we were sure they would spill the beans regarding the mission.

Prior to catching a flight that night, we went back to the squadron, and the Thai operations officer told us the training had been suspended for four days because they were involved in a mission. We knew, of course, it wasn’t a FAC/CAS mission, so I asked one of the more friendly pilots what was going on. He didn’t hesitate to lay it out for me. They were arming four OV-10s to carry two Mk 82 dumb bombs each. Those are 500-pound high-explosive and make quite a boom. On the Bronco, they were attached to a single rack which was bolted to each sponson. The centerline tank remained on the aircraft in this configuration.

I asked ‘Pui’ (that was the pilot’s nickname) what they were bombing, and he said a heroin processing plant. I asked him where and, to my surprise, he pointed on a wall map to a site about 10 kilometers inside Burma (now also known as Myanmar). I thought it was good we were getting the hell out of Dodge, since they were going to be bombing a foreign country which may trigger something more serious. (Burma at that time had little or no air defense capability, but still …).

So off we went to Bangkok, and I re-reacquainted myself and the team with Patpong and Soi Cowboy for the next three days. We did a couple of touristy things but spent a lot of time in ex-pat watering holes in that city.

After a few days, we got a call from the Embassy and ticket pickup instructions to fly back to Chiang Mai and resume training. The timeline had been interrupted by four days of no training, so we had to adlib our training syllabus, but I think they learned the basics of what an airborne FAC is supposed to do. I asked ‘Pui’ how the mission into Burma went, and all he gave me was a thumbs up. None of us could get any further information from any of the pilots, so I suspect they were being told to keep their traps shut. In retrospect, I’m not sure their mission went well at all, and it could have just been action to appease the U.S. pressure. For all I know, the Mk 82s may have just made a few divots in the jungle to the north. It’s possible they didn’t even cross the border. So the results of that operation remain a mystery.

After another week or so of training, we said goodbye to the Thai Bronco pilots and returned to our base in California, flying peacetime CAS with an occasional deviation for an actual search and rescue (like looking for Dean Martin’s son) or other search missions.

Six or seven months passed, and I missed the more exciting (IMHO) flying in Asia, so I volunteered for a remote tour flying OV-10s at Osan Air Base. I was surprised when the assignment shoe clerks asked if I could be ready to go in a month. Hell yes!

As an aside, together with a first lieutenant at the Osan squadron, I flew the final Pacific Air Forces OV-10 sortie when we ferried it down to a small airfield in South Korea where it was wrapped up and put on a barge in August or September 1989. It was one of those that was given to the Philippines for their air force.

I enjoyed my Bronco flying in Korea, which was much closer to the action than the high desert of California. I was again appointed the chief of STANEVAL and, in early 1989, I got called to the group commander’s office. He asked me if I wanted to go back to Thailand. He further stated that I was a ‘by-name request’ to go back and give the same squadron more FAC training. Not only was I flattered, but I jumped on the opportunity. Kimchi and Bulgogi were good, but I yearned for some Tom Yum Gai and Pad Thai again. And I was to be solo on this MTT — just me and the Thais.

And that MTT was an entirely different story. I returned to Chiang Mai in February 1989 to the same RTAF OV-10 squadron and actually got some front-seat time. The new squadron commander was a young lieutenant colonel who was married to the king’s number-three daughter. She was a genuine princess, and he was called the Royal Consort.

The previous squadron commander (during my 1987 MTT) had gotten shot down in a Bronco when Thailand and Laos had a short-lived border dispute in late 1987. In fact, he had been captured after bailing out over the disputed area in Laos and was only released when a ceasefire was agreed upon and prisoners were exchanged. I didn’t see him during my ’89 MTT.

So that just about wraps up my story about the OV-10, although there were a few interesting things that happened on that MTT, as well. To conclude, it’s worth pointing out that I was single this whole time, with no kids that I knew of. So, I was very flexible in my personal logistics.

As for Thailand’s Bronco fleet, the last of these aircraft were finally withdrawn from service in 2004, after more than three decades of service. Eight of the former RTAF aircraft were provided to the Philippines, which today is the sole military operator of the type, whose aircraft continue the Bronco’s long tradition of counterinsurgency warfare in the Asia Pacific region.

Contact the author: Thomas@thedrive.com