Warnings to mariners to stay clear of certain areas of the Atlantic Ocean, spanning from the coast of France to an area just north of Bermuda, due to upcoming “missile operations,” indicate that the French military will carry out a long-range ballistic missile test sometime in the next month or so. The exact locations of the four off-limits zones have raised questions about whether this launch will be a test of a new variant of France’s M51 submarine-launched ballistic missile, or SLBM, a key component of the country’s nuclear deterrent capabilities, or even a hypersonic weapon.

The navigation warnings, which include a box right off the French coast in the Bay Biscay, two more in the North Atlantic, and the one near Bermuda, first appeared online on April 21, 2021, and will be active from April 28 until May 21. The notices use arbitrary letters to refer to the zones, defining them, from east to west, as A, B, D, and C. Long-range missile launches in the Atlantic, in general, are not uncommon, with the United States, as well as its allies, regularly making use of the space that this body of water offers for these kinds of tests.

The A, B, and D areas show a path that is very reminiscent of one laid out in an earlier set of navigation warnings last year. Those off-limits areas turned out to be related to a test of an M51 SLBM fired from the Le Téméraire, one of the French Navy’s four Triomphant class ballistic missile submarines, or SSBNs. The Triomphant class boats can each carry up to 16 M51s.

However, in this case, there are at least two notable differences between those warning areas and the ones set to go into effect later this week, as Marco Langbroek, a Dutch archaeologist and Space Situational Awareness consultant at Leiden University in the Netherlands, was quick to point out on Twitter and on his blog. The first and perhaps most obvious is that the C area is distinctly offset from the ballistic trajectory laid out by the other three areas. The other important distinction is that the eastern edge of the A area, in this instance, is right up against France’s northwestern coast, and the DGA Essais de Missiles, the country’s main ballistic missile test facility, which could indicate a launch from a site on the ground, rather than somewhere off the shore.

The offset nature of the C area immediately raised questions online about whether this could indicate a test of a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle, rather than just another M51. In 2019, the French Ministry of Armed Forces had announced the award of a contract to ArianeGroup for the development of what was described as a “hypersonic glider demonstrator” as part of a program called the Véhicule Manoeuvrant Expérimental, or Experimental Maneuvering Vehicle, also abbreviated V-Max. At that time, the plan was to conduct a test of that vehicle in 2021.

“Many nations are procuring such weapons, and we have all the necessary skills to develop one,” French Minister of Armed Forces Florence Parly said in announcing the contract. “We could not wait.”

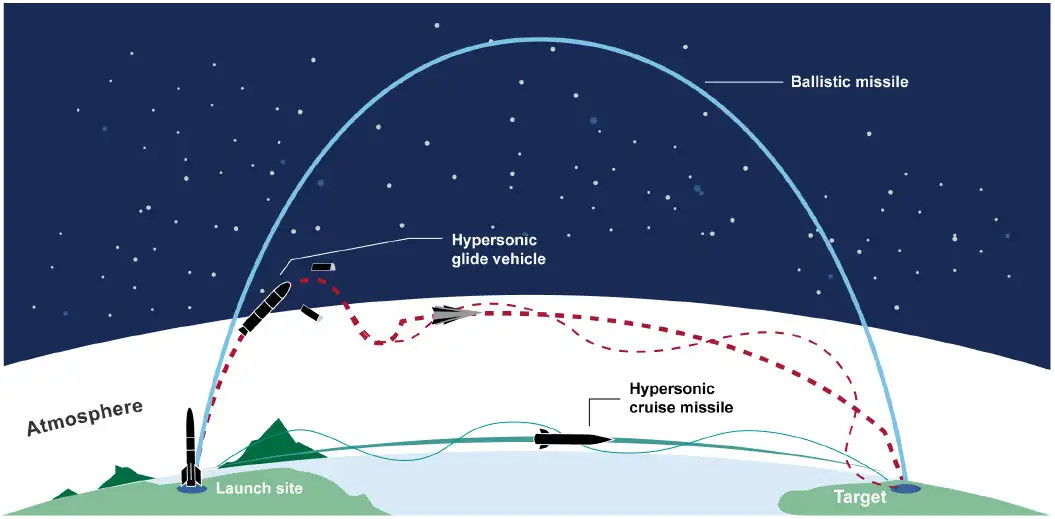

Hypersonic boost-glide weapons typically use rocket boosters that are similar, if not identical to ones used for more traditional ballistic missiles, to get to the vehicle to a desired altitude and speed. After that, the vehicle is released and glides down toward its target, making highly irregular movements, along an atmospheric flight trajectory, all at hypersonic speed, defined as anything above Mach 5.

The vehicle’s maneuvering is much less predictable than is found on more traditional ballistic missiles, even ones with advanced maneuvering re-entry vehicles. This combination of speed and erratic movements make these weapons particularly difficult to spot and track, let alone defend against. All this reduces the time in which an opponent has to react, at all, including attempting to relocate critical assets or otherwise seek cover, making boost-glide vehicles an ideal choice for prosecuting targets surrounded by dense integrated air defense networks.

France no longer has any operational land-based ballistic missiles, so a test of the V-Max design could also help explain any use of a launch site on the ground, rather than from a submarine. The U.S. military has tested hypersonic boost-glide vehicles from submarines and land-based test sites.

However, as noted, back in 2019, French authorities only said that the very first V-Max test would take place in 2021. It would be very unusual to even plan to conduct an initial flight test of a new boost-glide vehicle design, which are notably complex, across such a long distance. For example, the U.S. Air Force recently attempted to conduct the first live aerial launch of its AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW), which carries a hypersonic-glide vehicle. The weapon never even left the wing of the B-52 bomber carrying it in that test, but even if it had, the plan was always for the vehicle to disintegrate entirely after being released at the desired speed and altitude, simply demonstrating the entire system’s ability to successfully complete its initial phase of flight.

“It would be very atypical for an initial flight test of a hypersonic test vehicle to be on a full-range SLBM,” Scott LaFoy, Program Manager for National Security & Intelligence at Exiger Federal Solutions and an expert on missiles, space, and nuclear weapons technology, told The War Zone. “2019 interviews with DGA’s Joël Barre indicate that initial V-maX tests would utilize a sounding rocket for its initial stage.”

There also appears to be some debate as to whether the V-Max effort has shifted focus, at least in part, from a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle to an air-breathing hypersonic cruise missile in the past two years. “Under the V-max (Experimental Maneuvering Vehicle) program, France plans to modify its air-to-surface ASN4G supersonic missile for hypersonic flight by 2022,” according to a December 2020 report on hypersonic weapon developments from the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

“I observe however that the first three areas from the Navigational Warning are of similar size/shape and at similar distance to the launch site as in the June 2020 M51 test, so this could well be another M51 test,” Marco Langbroek, the Dutch archaeologist, also told The War Zone directly. “The off-set position of the target area probably points to the MIRVs being deployed from the post-boost vehicle at a sideways angle to the original launch trajectory.”

MIRV stands for Multiple Independently-targetable Reentry Vehicle and refers to ballistic missiles that carry multiple warheads on a single payload bus that are then released in the terminal stage of flight to strike individual targets. The M51 SLBM can carry up to 10 reentry vehicles, each loaded with a single nuclear warhead. The improved, longer-range M51.2 variant, which began entering service in 2016, carries new reentry vehicles with new Tête Nucléaire Océanique (TNO) warheads, each with a reported yield of around 150 kilotons. The earlier M51 and M51.1 versions were loaded with reentry vehicles carrying TN 75 warheads, with reported yields of approximately 110 kilotons, which had also been used in the preceding M45 SLBM design.

Releasing the MIRVs at an oblique angle might, but does not necessarily have to mean there has been a change to their design or that of the payload bus. “This could be due to how close to the U.S. East Coast and shipping lanes that a nominal trajectory would take or because there is a specific aspect of their reentry-vehicles maneuverability or post-boost vehicle that they are testing,” LaFoy said. No matter what, it is interesting to note that the final leg of the M51 test last year was much further south.

“The only oddity is that the launch appears to be from land, not from a submarine,” according to Langbroek. With that in mind, it’s important to point out that there is a further improved M51 variant presently in development, the M51.3, which will have even greater range than the M51.2, among other improvements. Firing an SLBM from the land could indicate a test of a new variant that is not mature enough to safely fire from an actual submarine. DGA Essais de Missiles does have a land-based submerged test platform, to simulate the launch of SLBMs without using an actual submarine, which it has used in previous M51 tests, as seen in the video below.

“Since the launch appears to be from land, it could potentially be a test flight of the new M51.3 SLBM that is in development,” Hans Kristensen, Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, told The War Zone. “The missile is an improved version of the current M51.2 deployed on the SSBN fleet and it is potentially possible the upcoming test flight includes an improved payload bus or new reentry bodies.”

There had been some discussion about whether the French SLBM test last year might have involved an M51.3 missile, as well.

“I don’t think launching from the submerged pool is particularly weird, since they do that every now and again, and I’m not sure if that implies that there is more risk than usual,” according to LaFoy. He also added that, based on the information publicly available now, the M51.3 “may not see flight tests for another year or so.”

There is always some amount of risk during missile testing. In 2013, French officials initiated the self-destruct mechanism on an M51 missile after a test launch off the coast of France during which the first stage of the rocket booster malfunctioned. This is part of the reason why countries around the world conduct routine tests of even established types. With regards to strategic deterrence, this is particularly important to ensure that a country’s nuclear weapons can be reliably called upon, if necessary, and to make that clear to any potential adversaries.

France is generally very tight-lipped about any developments with regards to its nuclear arsenal, so it will be interesting to see what, if anything, we might learn after this upcoming missile test is carried out, no matter what it necessarily entails.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com