The CF-105 Arrow was a uniquely Canadian response to the Cold War threat of nuclear-armed Soviet bombers. The Arrow’s promised and demonstrated performance — as well as resplendent aesthetics — commanded attention around the world and garnered major excitement at home in Canada. This big interceptor, which was developed in the 1950s, never entered service but Canada’s emotional attachment to the plane still runs very deep. This combined with the program’s abrupt cancellation the better part of a century ago has created a bizarre breeding ground for wild rumors and conspiracy theories about a sort of secret second life for the jet after its official demise. As such, the Arrow has become something of the ghost of aerospace past that just won’t die.

In the early 1950s, rapid advances in the Soviet Union’s bomber fleet were being observed with concern around the world. Canadian studies aimed at producing a jet to defend against Soviet bombers initially focused on dramatically improving the existing Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck, which was an indigenous, two-seat, twin-engine subsonic jet. The Canuck was a capable machine that gave Canada many years of service but was not designed for high-altitude, high-speed interception. Efforts to increase the top speed and performance of the CF-100 design led to diminishing returns and a reevaluation of the entire program. Canada instead decided to start from the ground up and indigenously develop an all-new advanced interceptor.

Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Specification AIR 7-3 was published in 1953. It outlined Canada’s true need, calling for a potent, cutting-edge machine capable of reaching a Mach 1.5 cruise at 50,000 feet five minutes after takeoff. Additional requirements were a paltry range of 300 nautical miles for a mission at normal speeds and a range of 200 nautical miles for a high-speed intercept. Operations from a 6,000-foot runway and a 10-minute turnaround time on the ground were mandated, as well. The RCAF surveyed British, French, and U.S. manufacturers, ultimately determining that no existing design could fulfill its requirements. Avro Canada went to the drawing board and the Arrow was born.

The new plan was realized in 1957 with a rollout, and the two-seat Arrow’s first flight took place shortly after in 1958. The first Arrow, RL-201, achieved Mach 1.9 on its maiden flight. The promise had been kept.

First flight of the Avro Canada Arrow, on March 25, 1958:

Four aircraft, RL-201, RL-202, RL-203, and RL-204, were built and designated Arrow Mk 1. All the Mk 1 aircraft utilized Pratt & Whitney J75 engines and interim avionics. Ultimately, the design was intended to use the in-development Orenda Iroquois engine, an advanced turbojet of lighter weight and greater thrust than the J75. The Arrow Mk 1s flew a total of 66 times.

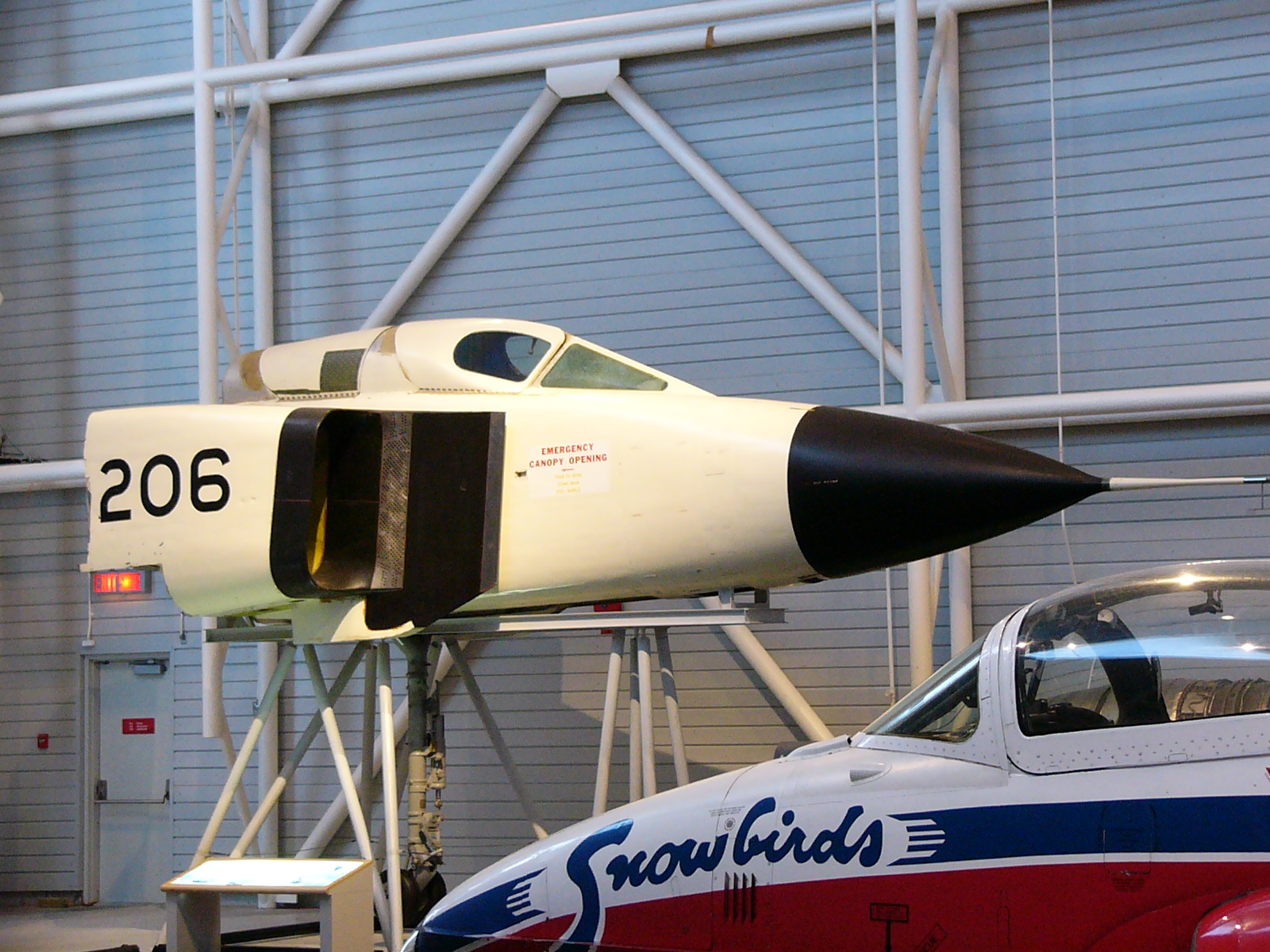

Two Arrow Mk 2s were built, as well, RL-205 and RL-206. Both these were considered production examples and were fitted with the more advanced Iroquois engines. RL-205 only flew once and was grounded due to engine problems. RL-206 never flew.

For many reasons, including the Arrow program’s prodigious price tag and the proliferation of Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) no jet could stop, the program was canceled on February 20, 1959, by newly elected Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.

The news was not entirely unexpected, but it was heartbreaking to many Canadians. To thousands of Avro employees, the bad news came via company president Crawford Gordon Jr. He took to the factory’s loudspeaker and reportedly referred to Diefenbaker as “That fucking prick in Ottawa.”

The cancelation left 14,000 Avro Canada employees almost immediately unemployed. The fallout extended to another estimated 15,000 aerospace contractors who lost their jobs as a knock-on effect. Since then, the day has been referred to as “Black Friday” in aerospace circles.

If the cancelation wasn’t harsh and abrasive enough, the order came two months later to destroy every part of the Arrow program, including the aircraft themselves. Nothing was supposed to escape the scrapper’s torch or shredder. The entire idea of the Arrow was to be liquidated, but that wasn’t quite how things turned out. A number of pieces of the aircraft and relics related to it did survive.

Regardless, sixty years later, the decision remains highly controversial. Industry engineers and defense experts still claim it almost single-handedly eviscerated Canada’s ability to natively develop and produce advanced aerospace products.

Officially, the story ends there. However, the Arrow morphed into a specter that lives on to haunt Canada. There’s an old Canadian joke that says the best thing that ever happened to America was the cancellation of the Arrow. America did benefit. A group of 32 engineers known as the “Avro group” took their knowledge and skills to NASA and ultimately served critical roles in the Apollo space program.

The Arrow wouldn’t go away quietly. Far-reaching rumors began immediately. Canadian writer June Callwood lived near the Avro plant in Malton, near Toronto, as a child. She claims that the day after cancellation, she and thousands of others heard the unmistakable crackling roar of an Arrow departing the area. Hardly conclusive evidence, but, to explain how that could have happened, conspiracy theorists point to photographs of the Arrows’ destruction, illicitly obtained from the air. The early pictures, before the cutting work began, confirm all the Arrows present, but the pictures from later in the process don’t appear to depict RL-202 at all.

RL-202 was an Arrow Mk 1 and so would not have been the obvious candidate for preservation. RL-205 and RL-206, with their Iroquois engines and fully equipped avionics suite, would have been more representative of the program’s final design goals. Avro Canada knew the program was in jeopardy and a plan to relocate an aircraft would have required immense planning. If a scheme to make off with an Arrow had existed, it stands to reason that a Mk 2 would have been chosen. Photographic evidence proves both Arrow Mk 2s were destroyed.

These circumstances leave a sliver of space for the conspiracy about RL-202. RL-202 had just been repaired from a landing gear malfunction and had been readied for flying when the program was canceled. With all the employees laid off and expeditiously seeking gainful employment elsewhere, no one would have been around to modify RL-202 up to Arrow Mk 2 production standards, let alone continue to fly and service it for a meaningful period of time.

Avro worked with Crown Assets and Disposal Corporation, which hired Lax Iron and Steel to handle all the scrap and residue. The owner, Samuel Lax, recalled strict controls in an undated interview. All scrapped parts were supposedly weighed and compared to the expected weights at Hamilton Scrap Yard. He also claimed RL-202, the specific jet conspiracies are predicated upon, was the first Arrow to be completely dismantled, which had occurred by June 24, 1959. The following August the RCAF was informed that the final melting down of component parts and remnant wreckage was complete, but some pieces still survived.

Not quite 10 years later, Air Marshal Wilfred Curtis, a World War II hero and head of the Arrow program, refused to answer in a 1968 interview if an entire Arrow had been spirited away. He suggested it was too soon to reveal the surviving Arrow’s location, and he needed to wait for a more favorable political climate. Curtis never spoke about the subject on the record again, and he died in 1977.

Further rumors of a surviving Arrow came from the United Kingdom. In 2008, and again in 2011, Martin-Baker Mk 5 ejection seats built for the Arrow appeared for sale on eBay in England. In 2011, the head of Martin-Baker business development, Andrew Martin, generated a letter of authenticity for the seats, confirming they were indeed from an Arrow. Further, there is reasonable evidence that the seats were installed and flown in the jet.

Chris Wilson, the managing director of Jet Art Aviation, which sells aviation collectibles, said in 2011 the two seats were a matched pair and likely came from an Arrow which escaped destruction and found a home in the United Kingdom. Wilson further claimed that a customer of his saw an Arrow at RAF Manston, in Kent. That claim is clearly problematic.

In the early 1960s, many aircraft were white, and many were shaped similarly. One prime example is the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) TSR-2, which was both similar in planform and white. The TSR-2 first flew in 1964 and was canceled in 1965. If the sighting wasn’t completely fabricated, there’s a chance that’s what was seen. By any logic, the sightings aren’t attributed to defined, credible sources within the aerospace or defense industries and can’t be relied upon.

Viewing the claim from an even bigger picture, the United Kingdom declassifies information at 30, 50, and 100-year intervals. The 30 and 50-year intervals have now passed. Not only was the Avro Arrow program public knowledge, both in development and defeat, but the United Kingdom had its own similar projects at the time, such as the aforementioned TSR-2. It’s unlikely an Arrow would have been of use to the United Kingdom. It seems highly unlikely that possessing an unclassified Canadian Mach 2 fighter would qualify as a national secret to be kept for 100 years; information that would have a grave effect on national security if compromised. Under the U.K. Official Secrets Act 1989, a confidential program such as one supporting an Arrow more likely than not would’ve been disclosed after 30 years.

As for the ejection seats in the United Kingdom, seats of this kind contain explosive charges necessary for the pilot to clear and egress the aircraft being abandoned. As with many conspiracies, the simplest explanation is perhaps most likely. Ejection seats are among the first parts procedurally removed before an aircraft can be safely cut up and destroyed. Museum-bound aircraft receive inert ejection seats that have been permanently “safed.”

In keeping with the orders to destroy everything, no complete Arrows were allotted to museums. Martin-Baker confirms that fewer than 20 seats were built for the Arrow program. The specific installed seats were removed before the aircraft began to be scrapped. There’s no verified chain of custody for these seats. We only know for sure that they came from an Arrow. Nothing beyond blind hope sprinkled with fantasy suggests they could’ve been removed in England from an airworthy aircraft.

In 1998, 40 years after the Arrow’s cancellation, an organization that called itself Arrow Recovery Canada, led by Andrew Hibbert, started scouring Lake Ontario for one of nine 1/8th scale test models of the Arrow that were strapped to rockets and launched from Point Petre, Ontario, at supersonic speeds. They spent between 1999 and 2006 surveying the area. For three years from 2006 to 2009, they dived to investigate targets that had been detected by sonar but didn’t find what they were looking for.

They had zealous competition. Ed Burtt, a shipwreck diver, was looking for the models as well. In 2018, a third project looking for the same models — called Raise the Arrow — funded by the OEX Recovery Group, found, and recovered a delta-wing test model from the Arrow program. It wasn’t the 1/8th scale model they were looking for, but it was a celebrated find. That model was restored and put on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. The search for the models continued into 2020. On October 8 last year, Raise the Arrow announced they found the 1/8th scale model they had been looking for and needed to determine how to raise it.

2020 was a big year all around for the ghost of the Arrow. Blueprints surfaced in January, of the type believed to have all been destroyed. A senior draftsman for Avro Canada, Ken Barnes, defied the 1959 order, snuck them out, and kept them in his basement. He never spoke of them in his lifetime and forbade his kids from going into the corner in which his workbench sat. After his death, they were discovered by his son. The blueprints are currently on loan to the Diefenbaker Canada Centre (the same Diefenbaker responsible for canceling the Arrow) and can be seen by visitors. Also smuggled out were RL-206’s nose cone and some panels. Those are on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, alongside the delta test model recovered from Lake Ontario. In the meantime, a full-scale replica was even built and placed on display at the Canadian Air & Space Museum in Toronto.

In 2010 Bourdeau Industries submitted a bizarre proposal to Stephen Harper’s Conservative government to replace Canada’s aging CF-18 Hornet fighter jets with updated Avro Arrows, instead of the officially favored F-35 Joint Strike Fighters. Canada’s retired Major General Lewis Mackenzie championed the proposal and said that the Arrow’s basic design still exceeded that of any current fighter jet. Major General Mackenzie is a highly respected officer who was at one time the Chief of Staff of the United Nations peacekeeping force in former Yugoslavia, but his claim about the Arrow’s capabilities as compared to fourth and fifth-generation fighter jets as of 2010 is easily disputable. Canada’s Associate Minister of National Defense at the time, Julian Fantino, agreed, stating that the Arrow was not a viable option 50 years after its demise.

As an impactful part of Canada’s history, the Avro Arrow is beyond reproach in its afterlife. It seems every last corner of its legacy has been explored and every known surviving part has been given the full artifact treatment. Even the depths of a great lake were laboriously scoured for 20 years to locate relics from the program. The reappearance of pieces, models, and plans and their placement in museums speaks to the fact that even though the program came and went almost a lifetime ago, it has been duly shown respect through commemoration. While fragments and mementos probably still exist in basements and warehouses throughout Canada, it doesn’t mean a jet is out there or ever was.

Why has its legacy persisted? The myths that have carried the Arrow beyond its resting place are a common vein with aircraft that become the source of national pride. For the sake of comparison, the SR-71 program was one of the United States’ greatest technological achievements. Its fans and proponents never wanted to admit that time had passed the SR-71 by, they didn’t want it to retire, and when it did, they assumed it was still out there somewhere, flying in secret. The Arrow is similar in its own way. The dream of what could have been is a tough thing to let go of.

Over six decades later, it may finally be time to lay the conspiracies and rumors surrounding the CF-105 Arrow to rest, but that doesn’t mean we can’t admire just how much of a technological marvel and a source of collective pride the aircraft could have been for Canada.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com