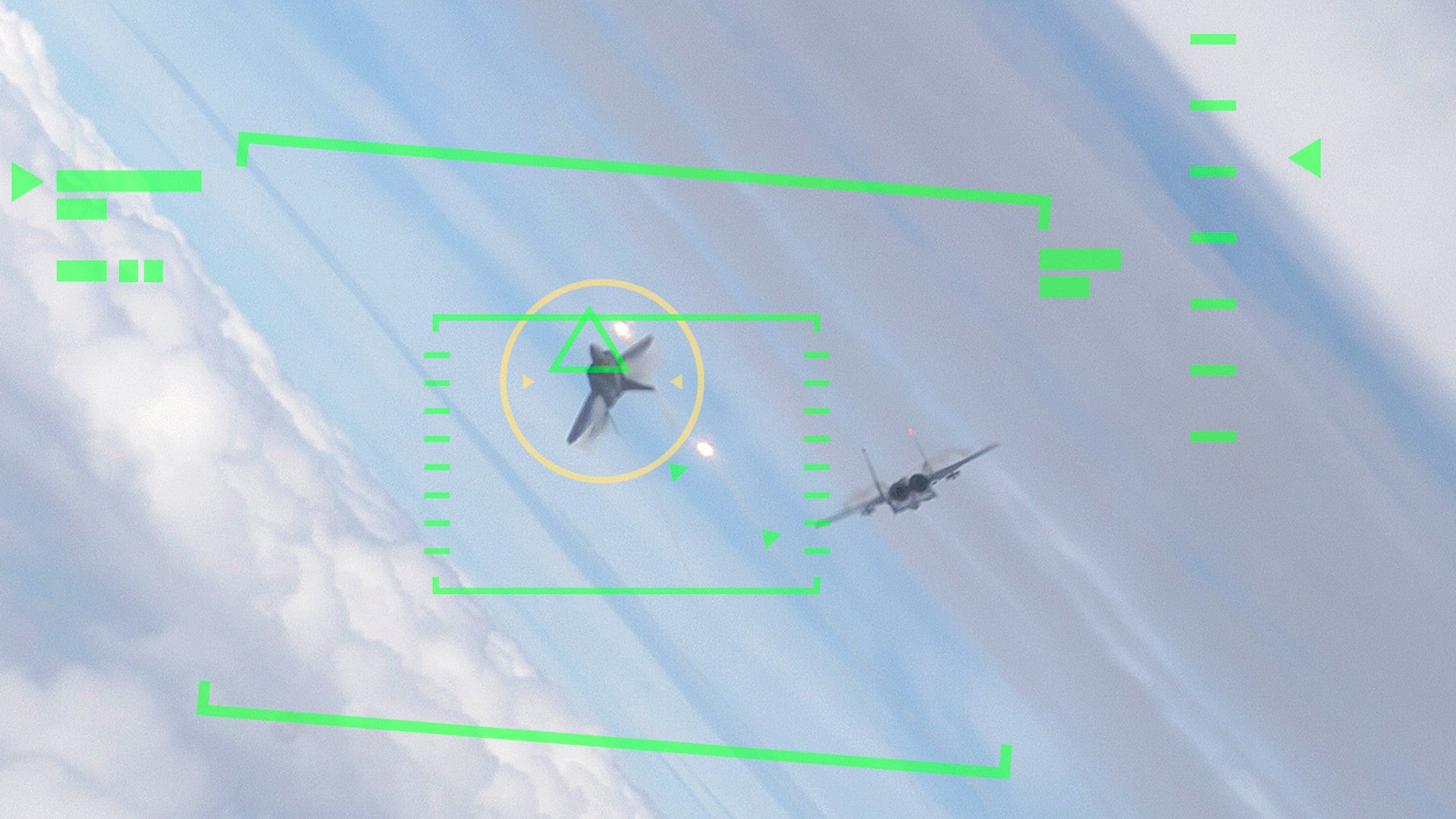

The Air Force is hoping to pit an autonomous drone equipped with an artificial intelligence-driven flight control system against a fighter jet with a human pilot in a little over a year. The service has described this effort in the past as a “big moonshot” that could revolutionize air-to-air combat in ways that have so far been limited to the realm of fiction – at least as far as we know.

Air Force Lieutenant General Jack Shanahan, head of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), revealed that the Air Force had set the goal of holding the faceoff in July 2021 during a remote event that the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies held on June 4, 2020. The Pentagon established the JAIC in 2018 to serve as a central point of focus for AI developments and related activities across the U.S. military.

Shanahan did not offer any details about the design of the unmanned aircraft that is supposed to take part in this in this future aerial duel or specifics about its planned capabilities. He did say that Air Force Research Laboratory’s (AFRL) Autonomy Capability Team 3 (ACT3), led by Steve Rogers, was still in charge of the effort, which Inside Defense first reported the existence of in May 2018. AFRL created ACT3 that year to focus on AI developments.

Regardless, the general concept of a fully-autonomous unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) capable of air-to-air combat, as well as air-to-ground strikes, hold great potential to fundamentally change the character of aerial warfare, something The War Zone

has explored in great depth in the past. At its most basic, a UCAV would be able to perform many of the same functions as manned aircraft, but would be able to make key decisions faster and more accurately, taking into account much more information in a shorter period of time, without any concern about being distracted or confused by the general chaos of combat. They can also be networked into swarms that work cooperatively to maximize their combat effectiveness at any given time far beyond what a human-piloted formation could.

The design of the drones themselves would be freed from parameters required to accommodate and protect a human pilot. Their planforms could be better optimized for aerial maneuvering and the pilotless aircraft could handle greater stresses during more aggressive flying than would be deemed too dangerous if a person was inside.

The drones would also likely be cheaper to build and maintain than manned fighter jets and, networked together into swarms, might not have to perform all missions equally well. In an air-to-air scenario, some might carry a powerful radar or an infrared search and track (IRST) system or other sensors to spot and track threats, while others, acting as missile trucks, would then engage those targets.

The Air Force, as well as other U.S. military services and foreign air forces, is already exploring how semi-autonomous “loyal wingman” drones might provide many of the same benefits when networked together with manned combat aircraft, something you can read about in these past War Zone stories. There are also separate efforts in progress to integrate similar AI-driven systems into manned aircraft themselves to help improve decision making and reduce pilot fatigue, among other benefits that you can find out more about in this previous War Zone piece.

In 2018, AFRL’s Steve Rogers had told Inside Defense that his team was looking to integrate AI-driven capabilities into manned fighter jets first. “Our human pilots, the really good ones, have a couple thousand hours of experience,” he said at the time.

“What happens if I can augment their ability with a system that can have literally millions of hours of training time?” Rogers continued “How can I make myself a tactical autopilot so in an air-to-air fight, this system could help make decisions on a timeline that humans can’t even begin to think about?”

It’s not clear what progress Rogers’ team has made on that front or toward the goal of a fully-autonomous UCAV since then. In his remarks during the Mitchell Institute event, Lieutenant General Shanahan implied that the scheduled faceoff was very much an aspirational goal and that it wasn’t clear if it would happen as planned.

Rogers “is probably going to have a hard time getting to that flight next year … when the machine beats the human,” the JAIC head said. “If he does it, great.”

It’s worth noting that in 2018 Rogers had told Inside Defense that the plan was for the dogfight to take place within 18 months, which would have been sometime before the end of this year. So, the July 2021 date is already seven months behind that schedule.

In addition, it’s not clear how this project is or isn’t connected to the AFRL’s Skyborg program, which is looking to demonstrate a loyal wingman type drone equipped with an AI-driven “computer brain” next year. The service has also said that it would be interested in installing a more mature version of the Skyborg system on a fighter jet-sized unmanned aircraft in 2022.

On top of that, the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has been working to develop AI-driven software that could help automate air-to-air combat as part of its Air Combat Evolution (ACE) program. It’s unclear how this project might inform any of AFRL’s developments.

There’s also no explanation of why the Air Force is only doing this now and why it appears to be taking so long. While there have certainly been important developments in recent years in artificial intelligence and general advanced computing, Lockheed Martin and Boeing, among others, both demonstrated highly autonomous prototype UCAVs years ago, which you can read about in this past War Zone feature. There have undoubtedly been more advanced unmanned aircraft developments in the classified realm, as well.

There have similarly been successful demonstrations of semi-autonomous loyal wingman type drones in the past. In 2015, the Air Force itself conducted a test, dubbed Have Raider, in which a pilotless F-16D Viper fighter jet flew linked together with piloted one. In a follow-on experiment, Have Raider II, which took place two years later, the unmanned Viper successfully broke away from its manned counterpart on command, flew a simulated mission, and then returned to formation.

The proposed faceoff also runs the risk of becoming a distraction from all this existing UCAV work and for future developments. Of course, there idea of holding a John Henry-esque man-versus-machine contest between a fighter pilot and UCAV, something that has been a staple of military and science fiction for decades, such as the opening moments of 2011’s Green Lantern or the entire premise of the 2005 movie Stealth, is certainly very alluring.

“The [F-35] competitor should be a drone fighter plane that’s remote controlled by a human, but with its maneuvers augmented by autonomy,” Elon Musk, founder of space launch firm SpaceX, co-founder of electric car company Telsa, and a general advanced technology entrepreneur, notably Tweeted out in February in an exchange in which he also declared the age of the manned fighter jet to be over. “The F-35 would have no chance against it.”

However, a one-on-one matchup, especially, is not necessarily indicative of how either platform would perform in a real, complex, multi-faceted combat environment filled with other friendly enabling assets and threats in the air and down below. The emphasis on dogfighting prowess has already waned somewhat in terms of how the Air Force, among others, expects to gain air superiority in the future as part of a larger force including elements from other services, as well as allies and partners.

It is only going to become increasingly more possible to dominate in the air without dogfighting and to develop and acquire fleets of unmanned aircraft around that reality that optimize low-observability (stealth), range, payload, and even cost, over high-performance. At the same time, the Air Force and the Navy have both repeatedly said that they expect their future forces to include both piloted aircraft and drones, though the exact mix is still being debated.

All told, it remains very much to be seen what AFRL’s manned-versus-unmanned aerial duel will actually look like in the end next summer, if it doesn’t just get pushed back yet again. If anything else, it will be a good gauge to see how far artificial intelligence and its air combat applications can be pushed, regardless of its actual battlefield relevance at this time.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com