There are few defense or aviation stories as enigmatic as the mystery surrounding the highly modified H-60 Black Hawks that were used during the operation to capture or kill Osama Bin Laden. Most remain perplexed that the helicopters not only emerged out of virtually nowhere, but that they also disappeared back into the deeply classified world even after becoming a very publicly known component of the historic raid. Although there are various claims as to their origins and the timeline of their development, in this War Zone feature, we have official documentation that clearly shows the development of a stealthy Black Hawk began way farther back than anyone has claimed.

The stealth Black Hawk and Bin Laden raid story helped launch my career to a certain extent. To this day, as far as I can tell, I was the first person who went on the record stating that the chopped-off tail left over from the helicopter that crashed inside Bin Laden’s compound in the wee hours of May 2nd, 2011 was not that of any known American helicopter, or one of any other national origin for that matter. Over the years that followed, I continued to report on any new details about the ‘Stealth Hawks’ and their shadowy past.

This included everything from originally proving the carcass left behind was, in fact, an H-60 derivative, to how creative ground lighting was used to mask the helicopters’ uniqueness while staging out of Jalalabad Airfield in Afghanistan, to how communications jamming equipment wasn’t installed on the helicopters due to weight issues, and pretty much everything in-between. My last installment dates back to October of 2015 when I related some of the claims in Sean Naylor’s book on special operations Relentless Strike, a read I highly recommend incidentally. We will get to some of the information in that book in a bit.

Since then, there has been no new credible information or sightings of the Stealth Hawks or even of their possible successors. Literally, the trail had gone cold. That is until I came upon a 1978 report worked up by Sikorsky for the U.S. Army Research and Technology Laboratory at Fort Eustis in Virginia—the same place where the Army cooks up its dream flying machines and capabilities to this very day. The report is titled Structural Concepts And Aerodynamic Analysis For Low Radar Cross Section (LRCS) Fuselage Configurations. Sounds boring and general enough, right? Well, it is anything but.

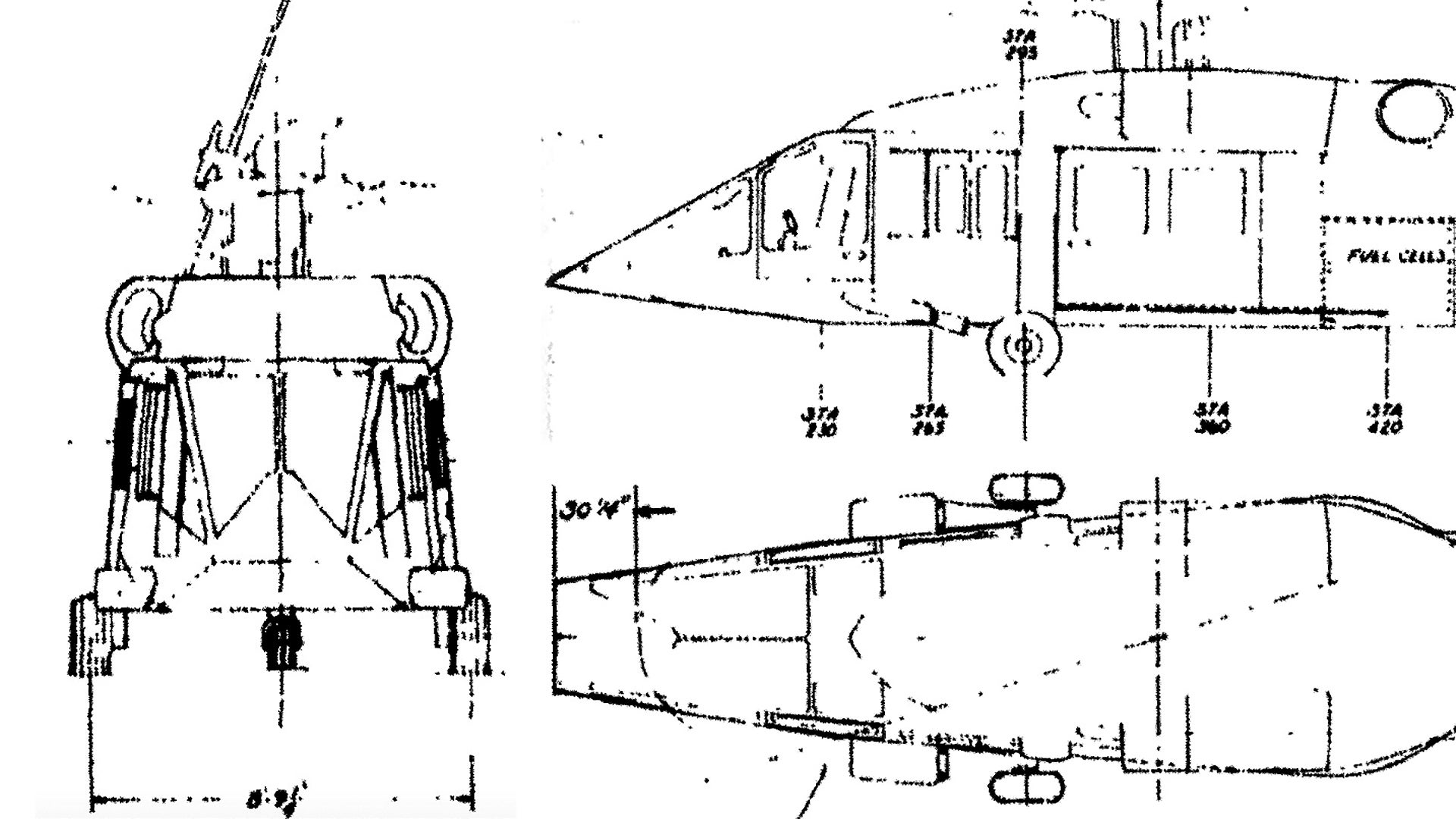

The 139-page report outlines in great detail how Sikorsky could turn one of its new UH-60 Black Hawks into a stealth flying machine. Three separate configurations were proposed for the study, each with varying degrees of modification to the baseline UH-60. The designs would be evaluated on weight, performance, radar cross section, cost, safety, risk, and maintainability. Two variants of each configuration were studied. One using conventional building materials and the other using advanced composite materials. The stealthy designs themselves came straight from the Army’s Applied Technology Laboratory. For the limited purposes of the study, the tail rotor would be left in stock configuration.

The study reads:

Three low radar cross section fuselage configurations for this study were developed by the Applied Technology Laboratory. The first configuration slightly modified the nose section from the baseline configuration; the second configuration changed the fuselage shape along the lines of a truncated triangular prism; the third extended canted flat side shaping throughout the fuselage. The tail surfaces and main rotor pylon fairing were the same as those of the baseline UH-60A.

It continues to describe each configuration in greater detail and provides drawings of each fairly wicked looking designs:

CONFIGURATION 1

The general arrangement of Configuration 1, shown in Figure 3, was developed from mold line drawing No. 20074180. This configuration alters the baseline fuselage forward of the mid-cabin section (the cockpit). Although this configuration is different from the baseline, the internal structure must be compatible with the forward cabin to avoid a heavy joining structure… The overall length is slightly increased due to this configuration.

CONFIGURATION 2

The general arrangement of Configuration 2, shown in Figure 4, was developed from mold line drawing No. 20074135. This configuration is basically a trapezoidal cross-section airframe having sides canted inward 30 degrees and made up of flat exterior structural panels. This configuration is wider at the bottom of the fuselage and narrower at the top of the fuselage than the baseline. This configuration is slightly longer than the baseline UH-60A, and its overall height is slightly larger than the baseline.

The increased length, width, and height of Configuration 2 does not allow an aircraft of this size to meet the air transportability requirements of the baseline. The narrow upper fuselage causes the pilot and copilot seats to be spaced closer to each other, and shoulder room in the main cabin is decreased. The main cabin floor is approximately 6 inches higher than the baseline from the ground. The increased floor-to-ground height causes difficulties for combat troops to enter or leave the aircraft quickly. Minor modifications of the mold lines for the transition and tail-cone sections were made to properly house the tail rotor shaft of the baseline UH-60A.

CONFIGURATION 3

The general arrangement of Configuration 3, shown in Figure 5, was developed from mold line drawing No. 20074136. This configuration is basically a flat side cross-section airframe having sides canted inward 50 degrees and is tapered in width from a narrow cockpit section to a transition section as wide as the baseline UH-60A.

The tail-cone is a rectangular section which is narrower than the baseline. The narrow cockpit causes the pilot and copilot seats to be spaced closer to each other; space for four-across seating in the main cabin is decreased. The cockpit and main cabin floors are at the same height from the ground as the baseline. The slope of the windshields may cause problems of visibility for the flight crew. Minor modifications of the mold lines for the transition and tail-cone sections were made to properly house the tail rotor shaft of the baseline UH-60A.

Three wireframe mold line models were also included in the report, one for each of the concepts:

The document continues to go into evaluating production concepts of the configurations using traditional aircraft building materials as one option and advanced composites as another. It describes how cost and risk would be impacted by either construction concept, as well as performance and what developmental pitfalls could potentially impact either choice. It’s interesting that while there were concerns over some safety and durability aspects of the composite materials construction concept, the authors noted that using graphite panels and other non-traditional materials would probably be needed to meet low-observable (stealth) goals.

An even more telling section is the one on how each design would impact performance compared to a stock UH-60A. In fact, there seems to be a bit of foreshadowing of the crash that occurred 33 years later inside Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan:

CONCLUSIONS

Comparison of the UH-60A attributes with the calculated results for the three proposed low radar cross section configurations indicate that:

1. A change in the UH-60A configuration to reflect the LRCS1 configuration caused a decrease in the drag of the UH-60A at α=00′. This decrease was reflected through a range of angles of attack (+8′ < α < -8′) with the exception of angles of attack of +8 and -8 respectively, where no change in drag was exhibited.

Configuration changes reflecting the LRCS2 and LRCS3 configuration showed increases of 11% and 17% respectively, of the UH-60A drag at α=00′ and as high as 21% and 29%, respectively, at angles of attack of +8′ and -8′. These changes do not reflect the required increase in stabilator size which would result in an additional drag penalty.

2. The LRCS1 configuration produces an insignificant change in lift compared to the UH-60A while the LRCS2 and LRCS3 configurations reflect an additional download of 40% of the UH-60A download at α=40.

3. Compared to the UH-60A, the LRCS2 and LRCS3 configurations demonstrate a substantial reduction in static stability which will require a redesign of the horizontal stabilator. This is primarily due to a reduction in tail effectiveness and an increase in fuselage instability. The reduction in tail effectiveness was estimated at 21% for the LRCS2 concept and 28% for the LRCS3 configuration. Minor changes in the pitching moment of the LRCS1 and LRCS3 configurations, compared to the UH-60A were calculated, however, the LRCS2 trend demonstrated an increase in slope resulting in an 83% increase in basic fuselage instability.

4. The three proposed LRCS configurations demonstrated an increase in vertical drag of 27% for the LRCS1, 106% for the LRCS2, and 70% for the LRCS3, of the basic UH-60A vertical drag. This increase in vertical drag is a direct result of the additional cross-sectional area and sharp edges presented to the downwash of the main rotor by the LRCS2 configuration. In the case of the LRCS3 configuration, the wedge type of cross-sectional area of the cockpit, the additional area of the main landing gear support structure and the presence of sharp edges presented to the main rotor downwash resulted in an increase in vertical drag as indicated. Finally, the increase in vertical drag for the LFCS1 configuration is a direct result of the wedge type cross-sectional area of the cockpit.

5. In comparison to the UH-60A, no change in the maximum cruise speed and endurance of the LRCSl configuration was observed, however, a loss of 217 feet in hover ceiling and 12 feet in OEI service ceiling was exhibited. The performance of the LCS2 and LRCS3 configurations did not meet the performance requirements of the basic UH-60A. Decreases of 7 and 11 knots in maximum cruise speed, 805 and 520 feet in hover ceiling, 248 and 740 feet in OEI service ceiling, and 0.14 and 0.19 hour in endurance were calculated for the LRCS2 aid LRCS3 configurations respectively.

Clearly, the more elaborate the stealthy modifications to the baseline H-60 design, the more penalty was paid in drag, overall performance, and especially general instability. This largely vibes with many of the claims about the two helicopters used in the Bin Laden raid over three decades later. These included major performance deficiencies, handling quirks, and were considered by some as downright unstable. Relentless Strike talks about this in detail, stating:

“The additional material that made the helicopters invisible to radar also added weight and made them difficult to fly. This gave Team 6’s most experienced men pause. Rehearsals had revealed that the “helicopter was very unstable when they tried to hover,” said a Team 6 operator. “Those things had been mothballed. The [pilots] hadn’t flown them in a while, but they got back out there.

…

“The helicopters were really forced on us,” a Team 6 source said. “These newfangled helicopters that had never been used before.” During initial planning meetings, McRaven had told Red Squadron to “look at all options” as they considered how to conduct the mission… In Team 6, there were different opinions about whom to blame for the insistence on using the helicopters. Some operators thought the CIA was driving the decision. Others attributed it to McRaven. “He wanted to use these newfangled helicopters,” said an operator. “He sold it to the president that way: These things are invisible to radar, they’ll get in, the [Pakistanis] will never know we were there.” When the helicopters proved unstable during training, the JSOC commander refused to revisit the decision, the operator said.”

It remains unclear if a non-stealthy MH-47G or MH-60M special operations helicopter would have experienced the same unrecoverable issue that the Stealth Hawk did that night over Abbottabad, but other factors beyond the helicopter’s known deficiencies came into play in that crash. Namely a far warmer than expected night in the already lofty targeting area and the fact that Stealth Hawks had trained on a model of Bin Laden’s compound in the Nellis Test and Training Range that used wire fencing for the compound’s solid walls.

Air circulated freely through the wire fencing, but stagnated inside the real McCoy, resulting in the Stealth Hawk experiencing a condition called vortex ring state (some have attributed it to settling with power, and really, it could have been a combination of both), which led to its crash.

It’s also worth noting that the 1978 study’s conclusions are based on a modified Black Hawk that still retains its stock four-bladed, unshrouded, tail assembly configuration. We know that the Stealth Hawk that went down Abbottabad had a very elaborate tail modification featuring a cover over its hub and five composite blades. This would have significantly reduced the helicopter’s radar and audible signature, but could have also further impacted its performance in a negative manner.

The Stealth Hawks also had a larger, rounded horizontal tailplane that is thicker in chord than the one found on its more traditional brethren. It also appeared to be forward-swept for radar signature reduction. The 1978 study mentions that a larger tailplane would have been necessary in order to keep the more elaborate configurations stable in flight, so seeing this unique feature of the Stealth Hawks used in the Bin Laden raid is yet another indication that the study was incredibly accurate for its age.

The report also doesn’t take into account other major acoustic reductions that we know would have been a major factor in a stealth Black Hawk design intended for the special operations mission set. Before there were major initiatives to examine reducing the radar signature on helicopters, there were ones to drastically muffle their sound output that made it into an operational form. Naylor details the importance of reduced acoustic signature for a stealthy assault helicopter in Relentless Strike:

“The 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment and the combat development organizations that support it had been experimenting with stealth technologies for many years, beginning with a program to create a stealthy Little Bird. The program progressed to include the Black Hawk, the 160th’s principal assault aircraft. The work had two overall aims: to reduce a helicopter’s radar signature by giving it a different shape and coating it in special materials, and making the aircraft quieter, which usually involved development of a Fenestron, or shrouded tail rotor. (Much of a helicopter’s noise signature comes from its tail rotor.) The 160th took the issue of reducing aircraft noise very seriously. In training exercises the unit would time how far from the target—in time of flight—the rotor sounds could be heard. As a rule, the larger the airframe, the farther out the target could hear the helicopter. The 160th wanted to reduce the time between an enemy hearing a helicopter approaching and it arriving overhead by as much as possible. “Even [cutting] fifteen seconds is huge,” said a 160th veteran. “And thirty seconds is amazing, because then you can be on top of the target and fast-roping people down.”

Sound suppression measures would also have added weight and potentially aerodynamic inefficiency to the Stealth Hawks and thus reduced performance, further exacerbating their negative stability and general performance issues. The Stealth Hawks retained the four-bladed rotor hub system found on all Black Hawks, so it’s clear that the sound suppression was approached in a balanced manner against complexity and cost.

Beyond similarities between the projected deficiencies of a stealthy Black Hawk detailed in the 41-year old report and those of the real ones, the existence of this study gives us new context as to the timeline of the still highly classified program. Once again, Relentless Strike describes the Steal Hawk’s supposed genesis in a very similar fashion as to what I had heard and posited for years. Naylor states:

“The stealth Black Hawk gained almost mythical status, like a unicorn. “I remember first hearing about it … in 2000 to 2001,” said a Delta source. The program quickly gained traction. “I remember in 2004 hearing that it was a line item in the budget,” he said. Knowledge of the special access program was on a strictly need-to-know basis, and hardly anyone needed to know. Shortly thereafter the 160th regimental leadership came looking to 1st Battalion—the core unit of Task Force Brown—for two crews to go down to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, and start training on the new helicopters. In the end, one crew went after a couple of pilots volunteered. “I never saw them again,” said a 160th source. “They’d be permanently assigned out there.” The program became more formalized. The aircraft were based at Nellis [actually Area 51], but 160th crews trained on them at some of the military’s other vast landholdings in the Southwest: Area 51; China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station in California; and Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona. U.S. Special Operations Command planned to create a fleet of four and make them the centerpiece of a new covered aviation unit in Nevada. By 2011 Special Operations Command had canceled that plan, but the first two stealth helicopters still existed and certain 1st Battalion crews would rotate down to Nellis to train on them.”

As I had stated in the past, the events of 9/11 and the larger defense budgets that followed, which included large increases in spending on special operations, combined with the rising threat from rogue states with nuclear programs, accelerated the Stealth Hawk program, or at the very least, breathed new life into it if it had been underway in the 1990s. The RAH-66 Comanche stealth armed-scout helicopter program, an enterprise that sucked down billions in development dollars and was canceled in 2004, also provided Sikorsky with a very deep bag of already-paid-for tricks and solutions to directly incorporate onto a stealthy Black Hawk derivative. Taking the easiest to adapt tech from the RAH-66 and integrating it around the UH-60 would have resulted in a far lower-risk, faster, and more affordable program than starting having never built a stealthy helicopter before.

Regardless of the operational requirements, it’s also clear why the Army would have seen such a program as a decent consolation prize for the defunct RAH-66. In the darkness of the classified world, it would keep the stealth helicopter ingenuity and brain trust alive, while also allowing the Army to benefit from billions ‘wasted’ on Comanche without it being a political pawn for those on Capitol Hill or the bean counters in the Pentagon.

I had long posited that the Stealth Hawks were not the result of a ‘snap-on kit’ as it was widely described, but a full buildout around the UH-60’s core drivetrain and subsystems, an idea further backed up again by the 1978 stealth Black Hawk study. Such a design would have also benefitted from Sikorsky’s S-75 technology demonstrator that long predated Comanche.

The S-75 first flew in the mid-1980s and acted as a proof of concept for composite helicopter airframe construction utilizing many of the techniques described in the 1978 stealth Black Hawk study. With lessons learned from the S-75, Sikorsky was ready to work at building an operational stealth helicopter, whether it be a RAH-66 or a stealthy Black Hawk derivative. Clearly, only one option survived into the mid-2000s.

Being able to better access defended territories for special operations missions wasn’t just about the Global War On Terror, it was also about having the ability to neuter or at least drastically decrease the possibility that a less-than-stable state would get its nuclear arms pilfered by a non-state actor hostile to the United States. Pakistan’s growing nuclear arsenal, in particular, proved to be a unique problem, but by 2009, it was one that defense officials said they could deal with directly in an emergency. This was largely thought to include sending special operations teams in to secure nuclear warheads and material during a crisis, and even removing them. Many found cryptic statements by Pentagon leaders alluding to the U.S. having the ability to do this as indicative of a secret penetrating platform, or platforms, that would be survivable enough to make such a round trip feasible.

Just like the stealthy RQ-170 Sentinel drone that was devised to clandestinely spy on nuclear activities of friendly and enemy nations alike, a very low signature assault helicopter would allow special operations to quickly access targets in similar operating environments. And like the RQ-170 that was also developed in the mid-2000s and had a mission that sprung from a secretive stealth program decades earlier, we now know that the Stealth Hawks’ lineage can be traced back to the dawn of stealth technology.

Back in 1978, stealth was still in its infancy, although elaborate studies on advanced low-signature aircraft date back many years earlier. Just a year before the stealthy Black Hawk study was delivered, the Skunk Works’ Have Blue demonstrator, a plane that would give birth to the F-117 Nighthawk, first flew. Just four years before that, the idea of a stealth attack aircraft was just taking shape under the highly-classified XST program. So it really is amazing to think that the level of research into a stealth Black Hawk derivative was being done 41 years ago, and a year before the UH-60A Black Hawk even entered into operational service.

In the three decades between this 1978 study and the latter half of the 2000s—the latest that the prototype Stealth Hawks would have been delivered—beyond the S-75 and the RAH-66, there is something of a research and development gap. It is possible that the Stealth Hawk concept was born into a prototype state long before 9/11 and the aircraft were remodeled or a second set of prototypes were introduced in the mid to late 2000s as a result of the new geopolitical realities of the decade. Regardless, these aircraft were still experimental and for whatever reason, never made it into production, by the time they were brought out of storage for Operation Neptune Spear. The aircraft’s instability and restricted performance could have been a driving factor in keeping the program in a technology demonstrating and testing stage.

Yet according to multiple accounts, the Stealth Hawk concept was totally reborn again in the months and years after the successful mission into Pakistan. Naylor writes:

“In the early hours of July 3, 2014, two Black Hawks full of Delta operators crossed the border from Jordan into Syria, flying fast across the desert. Their destination was a compound outside the town of Raqqa, on the north bank of the Euphrates in north-central Syria. It was there, U.S. intelligence analysts believed, that a group calling itself the Islamic State—one of the two Islamist factions waging war in Syria—was holding several Western hostages, including at least two Americans: journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff. The intelligence came from several sources: FBI interviews with two European men that the Islamic State had held as hostages before releasing them, probably as a result of ransoms paid; satellite imagery of a building near Raqqa that matched the descriptions given by the Europeans; and information supplied by Israel.

This was not JSOC’s first raid into Syria. But unlike the October 2008 mission to kill Abu Ghadiya, which involved a few minutes’ flight across the Iraqi border, this operation involved penetrating 200 miles into Syrian airspace. For that reason, JSOC had chosen to use the latest version of the stealth Black Hawks that flew the Bin Laden raid. That mission famously left one of the two such aircraft then in existence burned to a crisp in bin Laden’s backyard. But since May 2011 more of the airframes had been constructed, and the program had expanded so that the 160th now kept a unit of about forty personnel under a lieutenant colonel at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, where the stealth helicopters were housed. As the use of the specialized airframes suggested, JSOC had spared little expense to prepare for the operation. The task force had been training for weeks on a replica of the compound they were going to assault. There had been “eyes on the target” for at least a week prior to D-day, reporting what they saw in short, encrypted messages. When the helicopters neared the compound, they were filmed by at least one armed drone overhead.”

There have also been claims that the stealth Black Hawk was in its second generation when the Bin Laden raid took place, with the older generation being used for the raid out of fear that losing one would compromise far too many technological secrets. The more advanced models are supposedly called Ghost Hawks or ‘Jedi Rides’ and they possess many improvements over their predecessors and are extremely low-observable by design. There is probably some truth to these claims, but it is more likely that the new generation became available after the Bin Laden raid and not before.

We have received multiple tips over the years indicating that a new Stealth Hawk program is indeed alive and well and has been used on real-world operations as Naylor describes. With Lockheed having purchased Sikorsky in 2015, one can only imagine the boost in low-observable knowledge base and technology Sikorsky now has at its fingertips. For all we know we could be on a third or fourth generation Stealth Hawk by now. In fact, I would put money on it. Their likely home? Tonopah Test Range Airport.

The prop helicopters used in the film Zero Dark Thiry caused a lot of online buzz and look similar to the concepts outlined in the 1978 report:

Such an aircraft would be an ideal complement to a stealthy fixed-wing special operations transport, especially in this day and age of the proliferation of ever more capable integrated air defense systems and anti-access/area-denial strategies. There is also the combat search and rescue issue to consider. As the U.S. moves to a tactical aircraft fleet dominated by stealth technology, how can traditional combat search and rescue assets go to rescue downed aircrews in places where the best stealth fighters couldn’t even survive? This alone seems to be justification for a small but potent low observable special operations helicopter fleet.

Regardless of what’s to come for America’s shadowy stealth helicopter capability, it’s amazing to think that it all began 41 years ago with this study. Clearly, they were on to something then, so we can only imagine what the Pentagon has its most elite special operations helicopter crews flying now.

As for when we might actually see the remaining Stealth Hawk from the historic raid? It’s anyone’s guess, but I think your best bet would be once the Obama Presidential Library in Chicago opens its doors or the CIA makes another big addition to their museum that you aren’t allowed to visit.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com