A new report has described how a catastrophic failure on the part of the Central Intelligence Agency, combined with the Chinese government’s steadily more sophisticated internet monitoring capabilities, led to the dramatic collapse of an American intelligence network in China and the executions of dozens of spies and their associates. The incident is just one example of how authorities in Beijing are overseeing the creation of an ever more effective police state, complete with technology and tactics straight out of a certain genre of near-future science fiction movie.

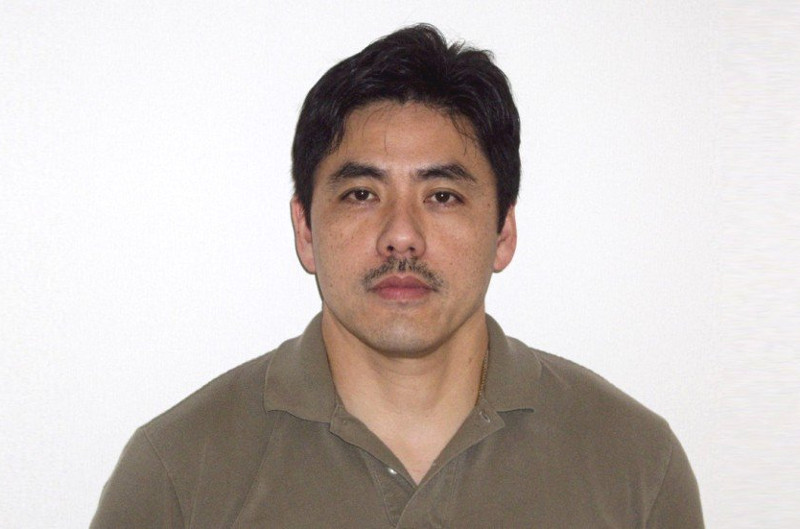

Earlier in August 2018, Foreign Policy revealed how Chinese state security officials were able to completely dismantle a CIA-run intelligence operation over the course of two years, beginning in 2010. The New York Times first broke the news of the debacle in 2017, but its sources either did not disclose or did not know exactly what had happened or the true scale of China’s response. In May 2018, U.S. officials charged former CIA officer Jerry Chun Shing Lee with conspiracy to commit espionage over the affair, nearly five months after indicting him for retaining classified information.

“When things started going bad, they went bad fast,” an unnamed U.S. official told Foreign Policy. “You could tell the Chinese weren’t guessing. The Ministry of State Security were always pulling in the right people.”

When it became apparent that there was a problem, the CIA turned to the Federal Bureau of Investigation to help uncover the source of the leak, according to the report. That investigation helped turn up Lee, who allegedly received tens of thousands of dollars to deliver information to the Chinese Ministry of State Security, which oversees both foreign and internal intelligence operations.

But the FBI also apparently determined that the duplicitous intelligence officer would simply not have been able to point the finger at so many American intelligence assets or their associates so quickly and accurately. For obvious security reasons, agencies such as the CIA typically keep the real identities of their sources highly compartmentalized specifically so that if one person gets compromised, the others are protected.

The FBI, with help from the National Security Agency, subsequently turned up a far more embarrassing truth. The CIA had likely burned these individuals itself when it unknowingly gave them a faulty piece of internet-based communications software.

The agency used this encrypted communications application to communicate with new sources in order to vet them. The system was separate from the CIA’s main links to established operatives in the field, again to shield those operations from infiltration.

Except the system was broken and contained one serious technical error. Experts at the FBI and NSA found they could use the less robust communications system the CIA used for its initial contacts to access the larger network.

“The attitude [of CIA officials in China] was that we’ve got this, we’re untouchable,” another anonymous official told Foreign Policy, who added they felt “invincible.” Even in 2010, this belief seems hard to understand.

For more than a decade at that point, the Chinese government had been developing and improving a wide array of powerful controls over the country’s internet, which have become known commonly as the “Great Firewall.” These systems are typically associated mostly with blocking websites and content on social media that the Chinese Communist Party deems objectionable. With the rise of Email and social media, they’ve also become part of a steadily more effective set of tools to track and silence dissent.

As such, the former CIA officer Lee would only have had to give the Ministry of State Security the names of a limited number of individuals to kickstart a major government investigation. Once the Chinese had arrested the first assets and acquired copies of the CIA’s communications software, or acquired that application by other means, they could’ve used information from that network, combined with the power of the Great Firewall, to isolate unusual web activity and locate other spies and potential associates. China’s counterintelligence officers might have had leads they were working through already to help quickly build a more accurate picture of the American intelligence operation.

Sources told Foreign Policy that Chinese authorities had subsequently executed at least 30 people, more than twice as many as the The New York Times’ initially reported, and had potentially killed or detained even more. China may have shared what it uncovered with its counterparts in Russia, leading to a chill in American human intelligence efforts there, as well.

The incident has reportedly pushed American intelligence agents in China to be wary of internet-based communications to the point of potentially abandoning it altogether in favor of old-school tradecraft, such as discreet, in-person meetings. The problem with this plan is that that the Chinese government is actively working to make such physical interactions dangerously difficult, too, with one particular region, the ostensibly “semi-autonomous” Xinjiang, acting as a sort incubator for a slew of draconian surveillance technologies.

Xinjiang, where Uighurs, a non-Chinese Turkic ethnic group that is predominantly Muslim, make up the bulk of the population, has been an ideal setting to test out new equipment and concepts of operation far from both Han Chinese and outside observers.

China has used the reality of Uighur Islamic extremists and separatists to paint the entire population, along with other Muslim ethnic groups in the region, as potentially suspect and there are reports that around a million of them are in concentration camps at present. There are also horrifying reports of forced marriages between Uighur women and Han men with the apparent aim of “breeding out” the group.

To help exercise this level of social control, China has put into place one of the most elaborate surveillance architectures in the world, complete with omnipresent cameras connected to monitoring stations running advanced facial recognition software, checkpoints with paramilitary police, and a system of systems all tied to a government-issued identification card that includes a “score” of how much a threat an individual poses to the state. Authorities have also begun implementing mass biometric data collection, including blood and DNA samples, to go along with other official information on file. All this can limit a person’s ability to buy goods and services or get a job.

After a spate of knife attacks in Xinjiang by alleged separatists, Chinese officials instituted a policy where cutlery vendors must physically laser-etch a QR code linked the buyer’s ID into the blade.

In July 2018, The Wall Street Journal reported that some 11,500 Uighurs that the Chinese government had approved to go on the Hajj, the sacred Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, had to carry special cards with a GPS tracker inside on a lanyard around their necks. Ostensibly for their own safety in the event of some sort of crisis, this system would obviously be able to monitor their every movement and it seems likely that anyone who decided to leave it behind would, if nothing else, take a serious hit on their social scorecard.

Among the most recent new additions to security apparatus in Xinjiang itself are small drones shaped like birds with realistically flapping wings, according to a June 2018 report from the South China Morning Post. These “Doves” can fly for thirty minutes and carry a small, color video camera and an ability to transmit the feed down to an individual on the ground. It reportedly has a GPS antenna and could be able to fly a pre-programmed route or operate under line-of-sight control.

The Chinese are “applying a very, very broad attempted solution to what they see as an ideological danger,” James Millward, who teaches Chinese history at The Georgetown University, told The Atlantic earlier in August 2018. “In Xinjiang, the definition of extremism has expanded so far as to incorporate virtually anything you do as a Muslim.”

It might be difficult for China’s government to apply the same sort of visibly extreme measures to ethnic Han or other groups elsewhere in the country and the Uighurs are suffering disproportionately, but the Chinese are certainly trying to expand the reach of many of these policies. They have already begun implementing the social scoring system on a more widespread basis.

Cops are now wearing Google Glass-style headsets with similar recognition capabilities to spot repeat offenders for crimes as minor as jaywalking. In the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, public restrooms use facial recognition software to give out only a specific amount of toilet paper per person. Even the police dogs have cameras.

As security personnel and automated systems scrape so much data in cyberspace and in the physical world, China has also begun to invest heavily in artificial intelligence systems that could help sort through it faster. Tech companies, eager to gain access to the Chinese market, have increasingly been working with authorities in Beijing directly

and indirectly on software and hardware to expand the government’s ability to censor information and monitor its citizenry.

Domestic companies still remain dominant, though, working hand-in-hand with the authorities to provide new messaging software for personal computers and cell phones that double as a way for the government to keep tabs on individuals. It’s a reality that has likely only made it more difficult for the CIA and other foreign intelligence services to employ their own distinct encrypted communications tools in China, which would easily stand out from normal phone and internet use.

This could have all have a serious impact on foreign intelligence collection, as well as political activism and government criticism, in China and that’s surely the point. The suggestion that the CIA is increasingly abandoning internet-based communication for operations in China indicates that at least some portions of the U.S. Intelligence Community don’t see a way to guard against threats such as the Great Firewall, at least in the near future.

That is no small victory for the Chinese and could threaten to give them an advantage given their own intelligence collecting successes in the United States and elsewhere. So far it seems to be working and it’s not clear what the United States, or anyone else, might be able to do about it, either.

“Will a system always stay encrypted, given the advances in technology?” an unnamed U.S. intelligence source asked rhetorically in speaking with Foreign Policy about what the CIA might be able to do in the future to safely communicate with its assets. “You’re supposed to protect people forever.”

Chinese officials, who are now turning to automated face-scanning machines to meter out toilet paper, are clearly hoping to make it as difficult as possible for external and internal actors to have any sort of unsanctioned impact.

Correction: The original version of the story incorrectly stated in a picture caption that the NSA headquarters was located in Northern Virginia. The NSA headquarters is at Fort Meade in Maryland. The CIA headquarters is in Northern Virginia.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com