For the first time in nearly three decades, Swedish authorities have issued a new civil defense brochure that calls on citizens to prepare for national emergencies by making sure they have adequate food, water, shelter…and access to reliable information. Though it doesn’t identify any potential adversaries by name, the strong emphasis on the potential for dangerous disinformation during a crisis is almost certainly driven by Russia’s continued overt and covert weaponization of traditional and new media and other information warfare campaigns.

The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, an element of the country’s Ministry of Defense, put together the new 20 page-long brochure, titled “If Crisis or War Comes,” which it unveiled in May 2018 and is also available in English. One will be sent to the almost five million residential addresses in Sweden. This isn’t the first time the agency has published one of these handouts, but it is the first time it has issued a new one since the end of the Cold War.

“Many people may feel a sense of anxiety when faced with an uncertain world. Although Sweden is safer than many other countries, there are still threats to our security and independence,” the pamphlet says in its introduction, titled “For the population of Sweden.” “Peace, freedom and democracy are values that we must protect and reinforce on a daily basis.”

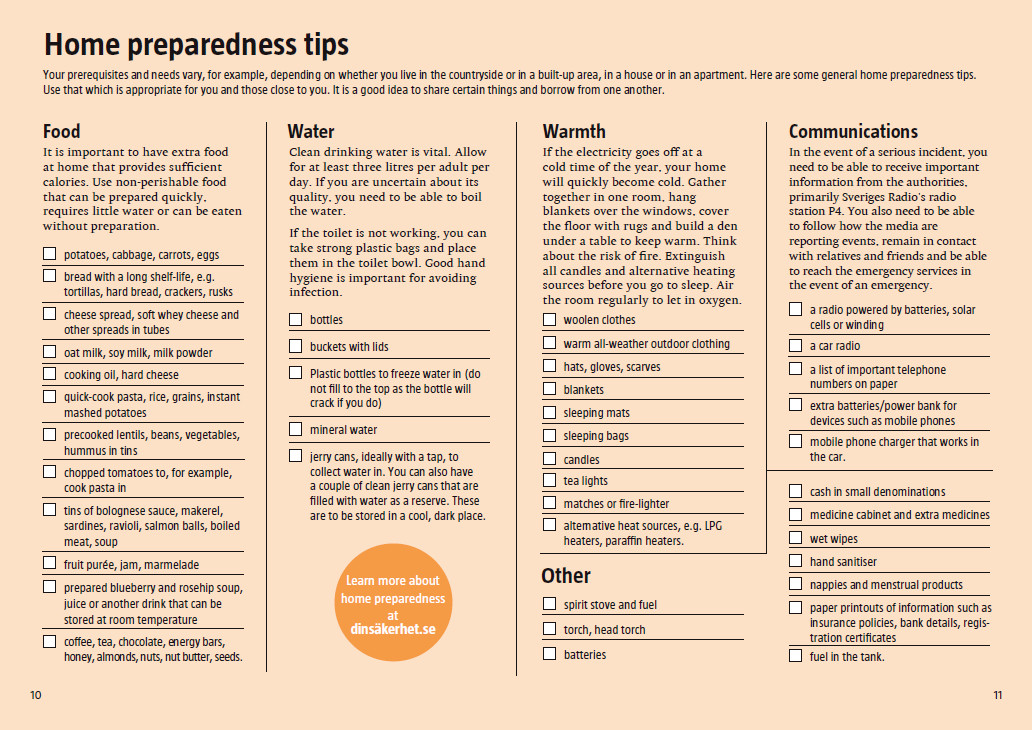

The guide is primarily meant to promote habits and preparedness for all sorts of emergencies, ranging from natural disasters to terrorist attacks to an outright foreign invasion. In the center, there is a checklist of suggestions for what Swedish homes should have at the ready.

These include three relatively typical categories – food, water, and warmth – as well as a miscellaneous section. Having a supply of clean water and shelf-stable, but nutritious food is good preparedness advice for people anywhere.

“Warmth,” rather than shelter more generally, is particularly important for Sweden specifically given the climate throughout the country. Average temperatures in the country’s northern regions can remain below zero all day during the winter months.

The “other” category includes various personal items, such as medicine, hand sanitizer, diapers, and feminine hygiene products. They also recommend having some spare cash in small denominations and “fuel in the tank” of the car in case you need to get out of the area in a hurry.

Elsewhere, the guide also provides information on Sweden’s national “Total Defense” doctrine, which various different agencies implementing policies that are all supposed to be fully functioning by 2025. The country’s military, which has mandatory conscription, as well as its expansive civil defense and reserve apparatus that applies to anyone between the ages of 16 and 70, are key components of this plan. Anyone in that age range could find themselves assigned one of a host of different tasks during a contingency to help defend the country. The state may requisition personnel property as appropriate, too.

In the video below, Swedish Air Force General Micael Bydén, Supreme Commander of the Swedish Armed Forces discusses the country’s Total Defense doctrine among other issues.

There are also details about how to decipher different warning siren sounds and where to go to seek shelter in case of an attack. Sweden also has an outdoor public address system, known as “Hesa Fredrik” or “Hoarse Fredrick,” outside municipal buildings and nuclear power plants. There are various web links and other information, as well as a number of different nation-wide emergency phone numbers.

And “if Sweden is attacked by another country, we will never give up,” the guide states bluntly near the end. “All information to the effect that resistance is to cease is false.”

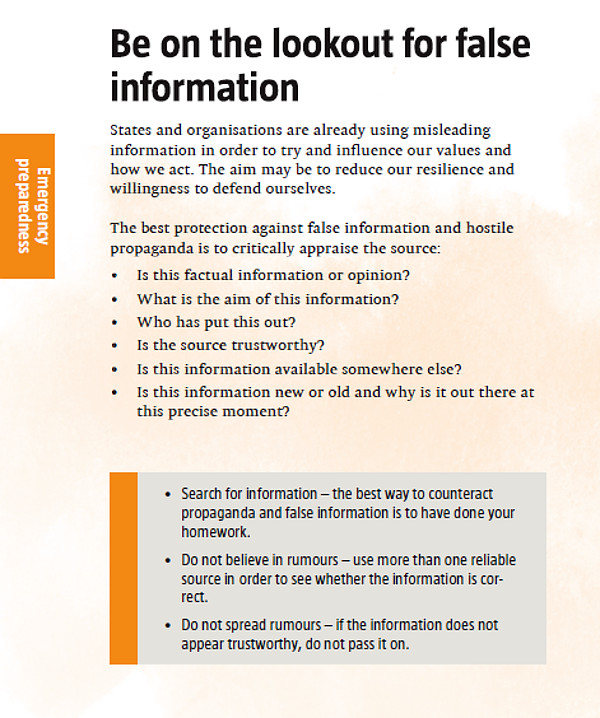

That last part is particularly important and it’s a theme that permeates through the entire handout. Two of the guide’s 20 pages are almost entirely dedicated to the dangers of information warfare during a crisis and the personal checklist includes a fifth “communications” category entirely separate from the others.

“We must be able to resist various types of attacks directed against our country,” the page on resistance notes. “Even today, attacks are taking place against our IT systems and attempts are being made to influence us using false information.”

Here is the full page on “false information”:

But it’s everywhere in the brochure. “Mobile networks and the internet do not work” is a potential problem that gets equal billing with “the heat stops working” and “the shops may run out of food and other goods.”

The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency warns people against sharing unconfirmed information “online or in any other way” during a possible terrorist attack. “Cyberattacks that knock out important IT systems” and “attempts to influence Sweden’s decision makers or inhabitants” require just as much resistance as “military attack, for example airstrikes, rocket attacks or other acts of war.”

“What is most important is that you have water, food and warmth and are able to obtain information from the authorities and the media,” the guide says in no uncertain terms. “In the event of emergencies and heightened states of alert, their [voluntary defense organizations] tasks include distributing important information to Sweden’s population. You are needed and your contribution makes a difference!”

The guide says that public broadcaster Sveriges Radio’s P4 station will be the primary reliable source of information in a crisis, along with state-run Sveriges Television, which has a teletext warning message system. At least one radio with rechargeable batteries – including solar or hand-crank power – and another one in the car are on the preparedness list specifically so you can tune in. “You also need to be able to follow how the media are reporting events.”

According to a report by the Canadian Broadcasting Company, previous versions also warned Swedes to be “on guard” against possible propaganda and to keep an eye out for possible enemy “spies and saboteurs.” But by the pamphlet’s own admission Swedish authorities put much less emphasis on those issues after the Cold War came to an end and peace and Europe for the foreseeable future appeared assured.

“For many years, the preparations made in Sweden for the threat of war and war have been very limited. Instead, public authorities and municipalities have focused on building up the level of preparedness for peacetime emergencies such as flooding and IT attacks,” the guide explains. “However, as the world around us has changed, the Government has decided to strengthen Sweden’s total defence [sic]. That is why planning for Sweden’s civil defence [sic] has been resumed.”

Once again, the brochure does not mention Russia or any other country by name. At the same time, it obvious that the Kremlin’s actions have been one of, if not the primary force driving the countries authorities to reexamine their civil defense procedures.

Russian authorities have adopted an increasingly aggressive foreign policy, which has included outright threats against Sweden, especially over the country’s growing ties with NATO members and the alliance as a whole. The Kremlin has also been using hybrid warfare tactics, including information warfare and electronic warfare attacks, against NATO and non-NATO opponents in Europe despite ostensibly being at peace with them.

For example, many national authorities and experts understand the Russian government to have been behind a number of cyber attacks to disrupt or disable computer networks in various countries since at least 2007. In that year, Estonia suffered a massive distributed denial of service attack that originated from Russia, which effectively blocked access to governmental and non-governmental websites, in what many cybersecurity professionals treat as one of the first state-sponsored incident of its type.

The Kremlin has since expanded its internet-based activities to include more complex operations, including setting up networks of fake social media accounts to rope in physical actors, knowingly or not, to influence elections and other political discourse, spread rumors and disinformation, and harass political opponents at home and abroad. There have also been hacks of Email accounts and other web-based personal information belonging to American and foreign military and government personnel, which trace back to Russia’s intelligence services.

The Russians have reportedly then used that information that information to try and discredit or harass those individuals. Some U.S. military personnel in Europe reported hacks only to be approached by strangers – likely intelligence agents from Russia – who knew a potentially dangerous amount about their personal lives.

For years now, Russian authorities, including president Vladimir Putin, have been publicly and officially trading in conspiracy theories and other dubious claims, deflecting from discussing its own behavior

typically by accusing others of being responsible for even more heinous crimes. Even after yet another independent report emerged in May 2018 full of evidence that Russia was at least complicit in the shootdown of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014, the Kremlin insists it had nothing to do with the incident.

The goal, of course, is to put forth so many convoluted and confusing stories that it becomes too difficult for the average individual to separate truth from fiction, making them inclined to question even the most rudimentary facts about a particular event. Often amplified by spurious social media accounts, the swirling narratives can quickly take on a life of its own, making it hard for anyone to trace it back directly to the Russian government.

Most notably, the Kremlin has employed these tools to meddle in a number of foreign elections. One of the best-known examples is its interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and have since reportedly attempted to do the same in various European polls.

This new reality almost certainly influenced the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency’s decision to prominently include resistance to “attempts to influence Sweden’s decision makers or inhabitants” in the civil defense guide. The Agency has avoided pointing the finger at Russia, so far, but has made it clear that the particular points in the guide about misinformation, among others, are immediately applicable.

“That is quite a big issue in Sweden especially now – we are going into elections,” Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency’s Christina Andersson told CBC. “It’s a problem in the society as a whole.”

The country will have a general election in September 2018. Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, head of the center-left Social Democratic Party, is facing a challenge from an opposition bloc in favor of closer ties with NATO and potentially joining the alliance formally.

This is something Russia has voiced its opposition to and some Swedish authorities have been clear about their concerns that the Kremlin might try to sway the election’s results. “The biggest threat to our security in that perspective is Russia,” Anders Thornberg, head of the Swedish Security Service, analogous to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the United States, told the BBC in January 2018.

The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency’s pamphlet is just one component of a nation-wide campaign to curtail information warfare campaigns in the run-up to the polls. Sweden has also implemented a curriculum to warn high school students about the dangers of propaganda and established a national “Facebook Hotline” where anyone can alert authorities to pages on the social media network that are falsely claiming to be official Swedish government sources.

It’s not clear whether these mechanisms will have a net positive impact. Reporting mechanisms, such as the Swedish hotline, which governments and private companies have implemented in the past in various ways on various platforms, have proven easy for nefarious actors and pranksters to game. Sometimes website operators have shut down legitimate founts of information as a result.

Other countries around the world are wrestling with the same issues. A number of national governments have even implemented laws against “fake news” that actually seem designed to provide a way to shut down political dissent.

Sweden clearly thinks its crisis preparedness guide is broadly useful and it has put it online in 13 total languages. But if nothing else, the handout makes it clear that information has become a ubiquitous weapon available to almost any entity interested in using it as such. In the age of social media and a 24-hour news cycle, defending against actual lies and deception has not only become more important, but it’s also harder.

“The best way to counteract propaganda and false information is to have done your homework,” the Swedish guide says. “Do not believe in rumours [sic] – use more than one reliable source in order to see whether the information is correct.”

It’s definitely a good place to start and valuable advice for virtually anyone. But there’s still a long way to go to find robust systems that can reliably counter the increasingly constant deluge of false or misleading information readily available, especially on the Internet, without inadvertently clamping down in legitimate free speech and political disagreement.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com