A brief clip of an official video from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, has appeared online, showing what looks to be a C-130 Hercules-type aircraft deploying or recovering a prototype unmanned system as part of the Gremlins drone swarm program. This is the first actual footage to emerge regarding the project, which is focused on demonstrating the feasibility of having groups of low-cost, air-launched, reusable drones perform a variety of roles.

The clip is presently available through the public hosting service Giphy, but it is unclear how long it has been online. We first noticed it earlier in April 2018 after Twitter user @MIL_STD posted it along with a quote from Eric DeMarco, who is President and CEO of Kratos Defense & Security Solutions.

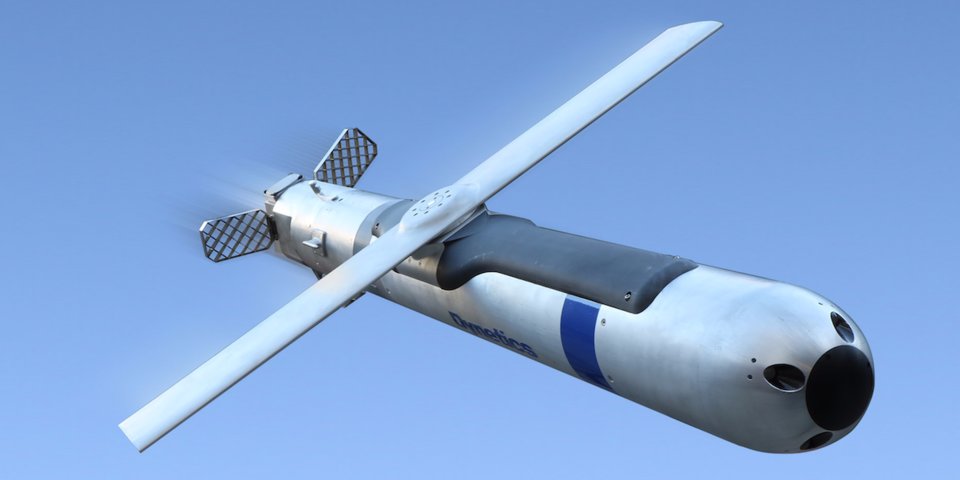

Kratos, along with Dynetics, General Atomics, and Lockheed Martin, took part in the first phase of the Gremlins program, which ended in March 2017. DARPA subsequently awarded additional contracts to Dynetics and General Atomics, but Kratos continued to be involved in the project as a subcontractor to the former firm.

“We have consistently demonstrated our success in rapidly designing and delivering low-cost, high-performance unmanned jet aircraft, and we see this as critical with respect to the Gremlins requirement,” DeMarco said in a press release in March 2017. “Our strategic focus is consistent with the Department of Defense’s Third Offset Strategy, which emphasizes the need to rapidly prototype innovative technologies to counter emerging threats and provide the United States with an asymmetric advantage over our adversaries.”

Gremlins, which first began in August 2015, envisions a cheap, short-life drone swarm that one or more aircraft can release in flight and another set of planes can then retrieve in mid-air after a mission. The basic concept of operations envisions a C-130-type aircraft – as seen in the video – as well as combat aircraft, such as fighter jets and bombers, releasing the swarm of Gremlins at a stand-off distance from enemy defenses.

The drones would then conduct this missions and another C-130 would retrieve them and return to base with them, where ground crews would be able to have them ready for another sortie within 24 hours. The minimum threshold requirement is for the low-cost unmanned systems to remain functional for just 20 missions.

DARPA says the primary tasks it envisions for Gremlins, at least at present, are intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and as a platform for other “non-kinetic” payloads, which could include electronic warfare systems. This would make sense since swarms offer significant potential as distributed sensor nodes and as a means of overwhelming enemy integrated air defenses ahead of a strike.

But this is just a small portion of the potential mission sets for swarms of small drones able to act autonomously or semi-autonomously, based on a fixed set of parameters and potentially in concert with other, larger unmanned or manned systems. As I wrote in a piece detailing Chinese swarm developments in January 2018:

Future swarms of small drones might also be able to carry electronic warfare jammers, emitters that mimic the signals of larger aircraft, equipment capable of conducting cyber attacks, or other systems to confuse or overwhelm an opponent’s defenses ahead of or during a more complex operation. A swarm of drones with small electro-optical or infrared cameras might be able to rapidly search a broad area for targets of interest discreetly and, with miniaturized data links, feed this information to other aircraft or other assets where it can be fused and exploited, giving their friendly force a more complete view of the battlefield and any potential hazards or targets of opportunity.

Even a swarm of small drones each with different modular capabilities installed could potentially conduct a broad array of tasks at once and in a resilient manner. Navigation system carrying types could help guide armed versions over long distances. Some armed variants could be capable of homing in on certain types of radiation—like radar emitters, air defense nodes, or even individual communications devices, while others can be capable of attacking prescribed targets that visually match images in their memory database. In this way, developments may be able to reduce the overall size and complexity of the basic underlying aircraft. This is an especially important consideration since the cost of launching dozens, or even hundreds of drones, could otherwise become prohibitive quite quickly, especially if the user doesn’t expect some or even all of them to necessarily survive.

Systems that are ostensibly for scientific research purposes, but that have sensors designed to monitor visual or other changes across a wide area could easily have military applications, too, acting as early warning nets or helping guard borders.

Drones swarms might even be able to eventually attack targets directly with small munitions or launch suicidal strikes against ground vehicles or ground-based elements of an integrated air defense system, such as radar arrays. When it comes to Gremlins in particular, a modular strike package of some sort, with a combination of sensors and a kinetic payload, could squeeze extra capability out of the aircraft on their last operational flights.

The clip does not appear to show Kratos’ Gremlins prototype, though. A public affairs representative for DARPA confirmed that the clip was from an official video, but said that it had been released yet and declined to comment further.

We do know that it is not General Atomics’ design. The company is, so far, the only one to publicly display its offering, which it simply calls the Small Unmanned Aerial System, or SUAS.

The unmanned system in the DARPA video has a distinctly different and more bulbous planform with four fins at the rear. General Atomics’ SUAS only has two rear fins in a completely different arrangement.

The rear fins on the vehicle in the animated picture have what appears to be of a grid or lattice design. This point towards Dynetics, which produces the GBU-69/B Small Glide Bomb, a precision-guided munition that has three fins of a similar shape. Kratos’ existing target and multi-purpose drone designs feature traditionally shaped control surfaces.

In addition, the C-130 visible in the video appears to be one that belongs to International Air Response. This firm offers a variety of specialized air services, including making their aircraft available for flight tests, and is a member of Dynetics Gremlins team.

Of course, grid fins are a well-established technology at this point and, among other benefits, offer a relatively easy way to fold control surfaces near flush against the cylindrical body of a missile, rocket, or other types of projectiles. This can help make the weapon or air vehicle more compact for storage and carriage before launch, which would almost certainly be an important consideration for the Gremlins project.

The video itself is almost certainly from the first phase of the project, which was supposed to include tests to examine methods for both launching and recovering prototypes from the rear of a C-130-type aircraft. The clip appears to show a winch system with a physical tether to the drone, but it is not clear whether this is part of the launch or recovery process, or if that system performs both functions. Reeling the vehicle in either direction would be good test points.

But while a tether could offer a low-cost means of releasing the unmanned systems, it might present greater difficulties in attempting to recover them and do so rapidly. It is possible that there is a secondary arm or another mechanism to quickly snag a returning aircraft that is not visible in the clip. General Atomics’ Gremlins’ concept art has depicted underwing pylons releasing drones via a fixed line, but with a more complex robotic arm for retrieving them afterward.

The complicated nature of this proposition is not entirely new. During the Cold War, the U.S. Air Force and the Central Intelligence Agency employed the Fulton Recovery System, also known as the Skyhook, to catch the parachutes on falling film canisters from spy satellites and early reconnaissance drones in mid-air, as well as snatch up downed aviators, special operators, and secret agents right off the ground.

This arrangement consisted of an aircraft with a large V-shaped frame at the front to snag the parachute or a line attached to a balloon. The object would then trail behind the aircraft, where personnel at the rear would use a separate line and winch to haul it aboard. The C-130 was the primary Fulton platform until the Air Force retired the system completely in 1996.

Physical hooks that allow one aircraft to retrieve another are an even older concept, dating back to the 1930s with the U.S. Navy airship USS Akron. This massive dirigible could launch and release Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplane fighters from a large internal hangar.

During the 1950s, the Air Force experimented with a number of air-launched and recovered aircraft schemes, both to provide fighter escort for long-range bombers and to extend the range of small reconnaissance aircraft. Modified B-29 Superfortress and B-36 Peacemaker actually flew experimentally carrying modified F-84 jet fighters and RF-84 reconnaissance aircraft, as well as the purpose-built XF-85 Goblin “parasite fighter.”

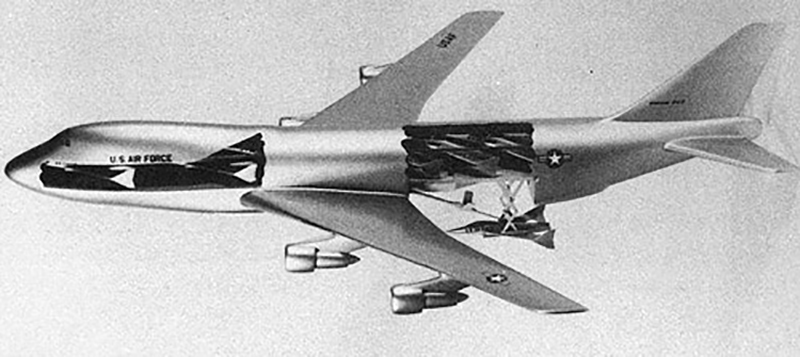

In the 1970s, Boeing revived the concept, suggesting that it could convert 747 airliners into flying Airborne Aircraft Carriers (AAC). In addition to being able to launch and recover 10 “microfighters,” the modified airliner would’ve be able to refuel them in flight, at least in theory.

So there is definitely a significant amount of existing history out there with launching and recovering aircraft in mid-air that Dynetics and General Atomics could tap into as they proceed with the Gremlins project. It will be fascinating to see what concepts they ultimately propose as the program moves forward.

DARPA’s first phase also included studies to examine ways to keep the individual drones cheap and easy to modify in order to accept new systems as necessary. There was also work on developing digital flight control systems to enable the aircraft to work together as a swarm.

The second phase, which began in 2017, is working toward maturing the experimental components into more functional prototypes for full-scale tests of a complete system. DARPA hopes that demonstration, phase three of the Gremlins program, will begin in 2019.

And though the agency said it couldn’t tell us anything more about the video, they did say there’s a new announcement about Gremlins coming soon. So it might not be long before we get more details about the project’s actual progress.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com