A new report has surfaced suggesting that White House Chief of Staff John Kelly and an unnamed member of the U.S. Secret Service got into a physical altercation with Chinese security personnel over the so-called “nuclear football,” a secure communications device inside an aluminum Zero Halliburton briefcase that enables the president of the United States to order a nuclear strike from virtually any location in a time of crisis. The Secret Service has denied that anyone got “tackled” during the alleged dispute, which may have occurred during President Donald Trump’s visit to China in 2017, but has not said outright that the incident did not happen at all.

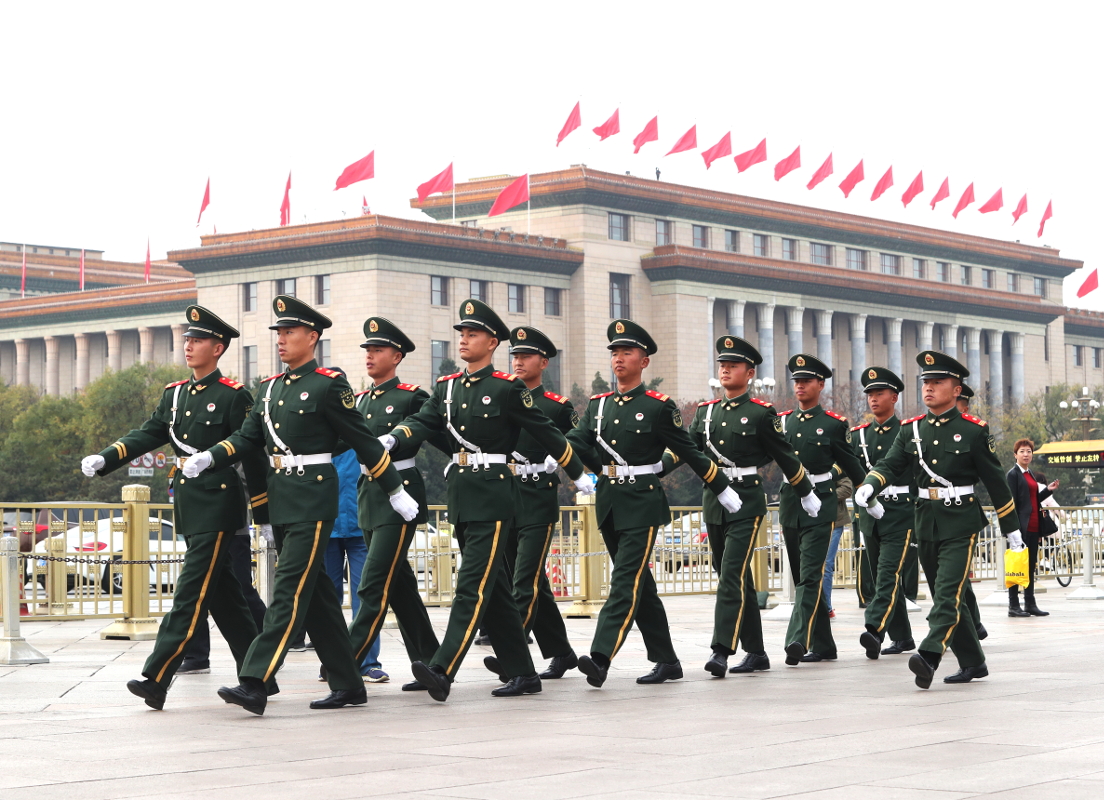

On Feb. 18, 2018, Axios, citing five anonymous individuals, first reported about the events, which happened on Nov. 9, 2017, while Trump was in Beijing as part of a larger tour of countries in Asia. As the president and his entourage made to enter the Great Hall of the People, a large government building in Beijing that serves as a meeting place for gatherings of the Chinese Communist Party and other ceremonial affairs, such as state visits, a Chinese security officer apparently attempted to block the individual carrying the football from following them for unknown reasons. That U.S. military aide is supposed to be near the president at all times.

“We’re moving in,” Kelly, a retired U.S. Marine Corps general, reportedly said after hearing what was going on from where he was in an adjoining room and hurrying over to take charge of the situation. After arriving he pointedly told the aide and other members of Trump’s team to just keep walking into the hall.

In the ensuing kerfuffle, a member of the Chinese security detail assigned to the Americans apparently grabbed Kelly, who shoved him away. According to Axios, a nearby Secret Service agent then tackled the Chinese officer, likely in response to what they interpreted as a potential threat to a senior U.S. official.

“FACT CHECK: Reports about Secret Service agents tackling a host nation official during the President’s trip to China in Nov 2017 are false,” the U.S. Secret Service wrote in a post on its official Twitter account on Feb. 19, 2018. The exact wording of this statement suggests that the incident was less rough that Axois’ sources had described it, but not that there had been no dispute over whether the aide could accompany Trump into the Great Hall.

Axios reported that the aide assigned to carry the football never lost control of the signature black briefcase during the scuffle and that clearer heads prevailed and calmed things down quickly. The unnamed individuals told the outlet that the Chinese apologized for the incident and both sides agreed not to make a public issue out of it, as well.

Even if the situation did not result in an actual brawl, any debate over whether or not the person carrying the football could accompany Trump would have been a major issue. Since at least the Cuban missile crisis, steadily improved versions of the unique piece of luggage, formally known as the President’s Emergency Satchel, have followed the president of the United States wherever they go, reinforcing the credibility of America’s nuclear deterrent as part of a larger set of procedures and failsafes to ensure “continuity of government” in a crisis.

The special presidential transport aircraft Air Force One with its unique command and control capabilities, other fleets of strategic military command and control aircraft, secure bunkers, and various standing plans for senior leaders to evacuate to those sites are all part of this broader contingency concept. The idea is to make it clear to potential adversaries that a sneak attack will not be able to neutralize the U.S. government and prevent the prospect of massive retaliation.

To use the satchel itself, the president would first identify themselves by inputting codes from a card they carry at all times, called the “biscuit,” and the device would establish a direct link to the National Military Command Center in the Pentagon and to Strategic Command, or even to a E-6B or E-4B flying command post should either location be destroyed. After that, they could order a nuclear strike using a pre-set “menu” of attack options the U.S. military has already put together. Advice can be had from the military attaché carrying the football, who is from any of the services and has a rank of O-4 or higher and who is well versed on the plans and their intended effects.

President Jimmy Carter reportedly demanded these simplified choices because of the very limited time in which he would have to decide how best to respond to an incoming nuclear assault or other major contingency requiring a response with nuclear weapons. There might be as little as 15 minutes available to make such a decision before enemy missiles arrive. There is no actual “big red button” in the bag that would immediately launch a nuclear strike.

You can read more about the procedures the president has to go through to initiate a nuclear strike here and here. You can also learn more about the Pentagon’s standing plans for following through on those orders here.

It’s not the first time the football and its handler has come up during the Trump Administration. In February 2017, shortly after Trump took office, Richard DeAgazio, a guest at the President’s Mar-a-Lago property in Florida took photos with a member of the U.S. military identified as “Rick,” who was the aide carrying the briefcase at the time, and posted them on social media. DeAgazio was the same individual who posted the now notorious images of the president looking at potentially classified documents regarding a North Korean missile test with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at a table in the resort’s dining hall.

In this newly disclosed incident in China, its not clear why the Chinese official initially attempted to block members of Trump’s team from the Great Hall in the first place. The U.S. government apparently gave the standard security briefing to their counterparts in China ahead of the trip, which they do whenever the president visits the country.

It is possible that there was simply some confusion on one or both sides as to the protocol and procedure and who the Chinese would allow to follow Trump into the Great Hall. It could also have been a more deliberate decision at some level to challenge the American delegation.

By the time he visited Beijing in November 2017, Trump had already spent much of the year threatening implied nuclear strikes on North Korea and accusing the Chinese government of not doing enough to pressure North Korean premier Kim Jong-un and his regime into curtailing their provocative missile and nuclear weapons tests.

The U.S. government had also formally censured Chinese nationals and companies it accused of enabling officials in Pyongyang to skirt American and international sanctions. The United States rightly continues to see North Korea’s use of China’s ports and other parts of that country’s shipping industry to import and export goods violation of various embargoes as a major issue.

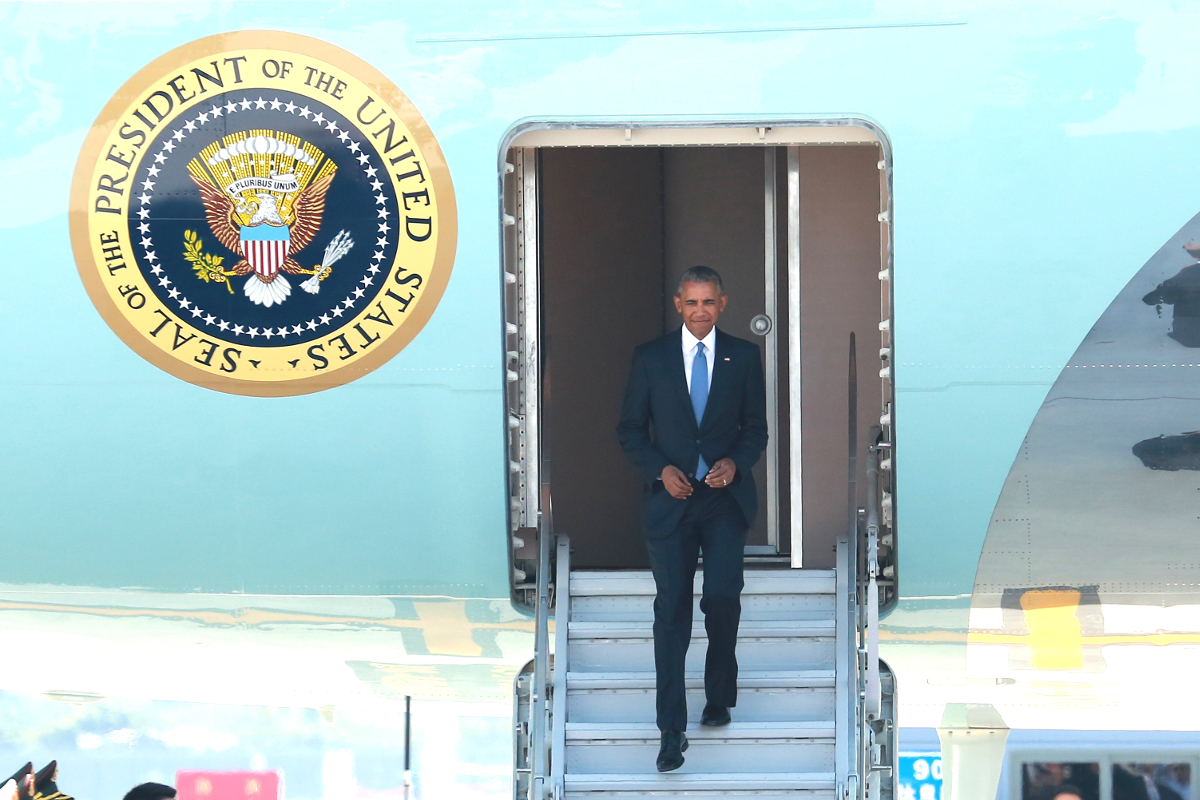

This wouldn’t be the first time Chinese authorities have at least given the appearance of snubbing a U.S. president with a debate over protocols and procedures. When President Barack Obama arrived in the city of Hangzhou in September 2016 for the annual G-20 summit, he had to unceremoniously exit Air Force One through a door in the plane’s lower fuselage due to a squabble over a mobile stairway.

As part of the massive array of supporting equipment that follows the president of the United States on international trips, the U.S. government had flown in their own mobile airstair to allow passengers to get off Air Force One. The Chinese reportedly agreed to this initially, but then changed their minds at the last moment.

This in turn created a commotion since the U.S. security detail complained that the local operator of the replacement airstair could not speak English and Chinese authorities refused to provide a bilingual substitute. Chinese officials eventually caved to American requests to just use their own equipment as they had planned, but by that point Air Force One was already almost on the ground and they decided to simply use the aircraft’s on board equipment in the end.

“This is our country, this is our airport,” a Chinese official reportedly said in a raised voice as Obama and those traveling with him departed the aircraft. Chinese state media subsequently slammed the U.S. government and American media for making an issue out of a simple misunderstanding, but many believed the actions were deliberate harassment in response to the Obama administration’s noted criticisms of China on various issues, including its vast territorial claims in the South China Sea and human rights.

Though Trump’s remarks toward China have fluctuated between combative and conciliatory during his presidency already, especially with regards to cooperation on the issue of North Korea, he has remained steadfastly critical of Chinese trade practices. In January 2018, he approved protectionist import tariffs on washing machines and solar panels coming from China and is moving to do the same with regards to Chinese steel.

His administration’s new overarching national security and defense strategies both identify China as a major political and economic opponent and there is a special section in the controversial Nuclear Posture Review dedicated to deterring authorities in Beijing. There is once again talk about reinforcing American military posture in the Pacific region in the face of the Chinese military’s growing capabilities and Trump recently nominated U.S. Navy Admiral Harry Harris, presently the head of U.S. Pacific Command and a major critic of Chinese policies, as the next ambassador to Australia.

As such, it’s very possible that there could be similar, low-level spats over basic protocol during future visits to China. But hopefully John Kelly, or anyone else, won’t have to get in an actual fight with Chinese officials over the nuclear football again.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com