After more than 16 years of U.S.-backed efforts to stabilize the country, American diplomats and other supporting personnel still rely on privately-operated helicopters just to safely get around Afghanistan’s capital Kabul. Now, a new State Department report says contractors responsible for assessing potential threats to those flights do not have the necessary security clearances and resources to effectively do their jobs. This all comes amid a separate report from a top U.S. government watchdog that suggests the international coalition is deliberately obscuring details about the dismal state of security across the country.

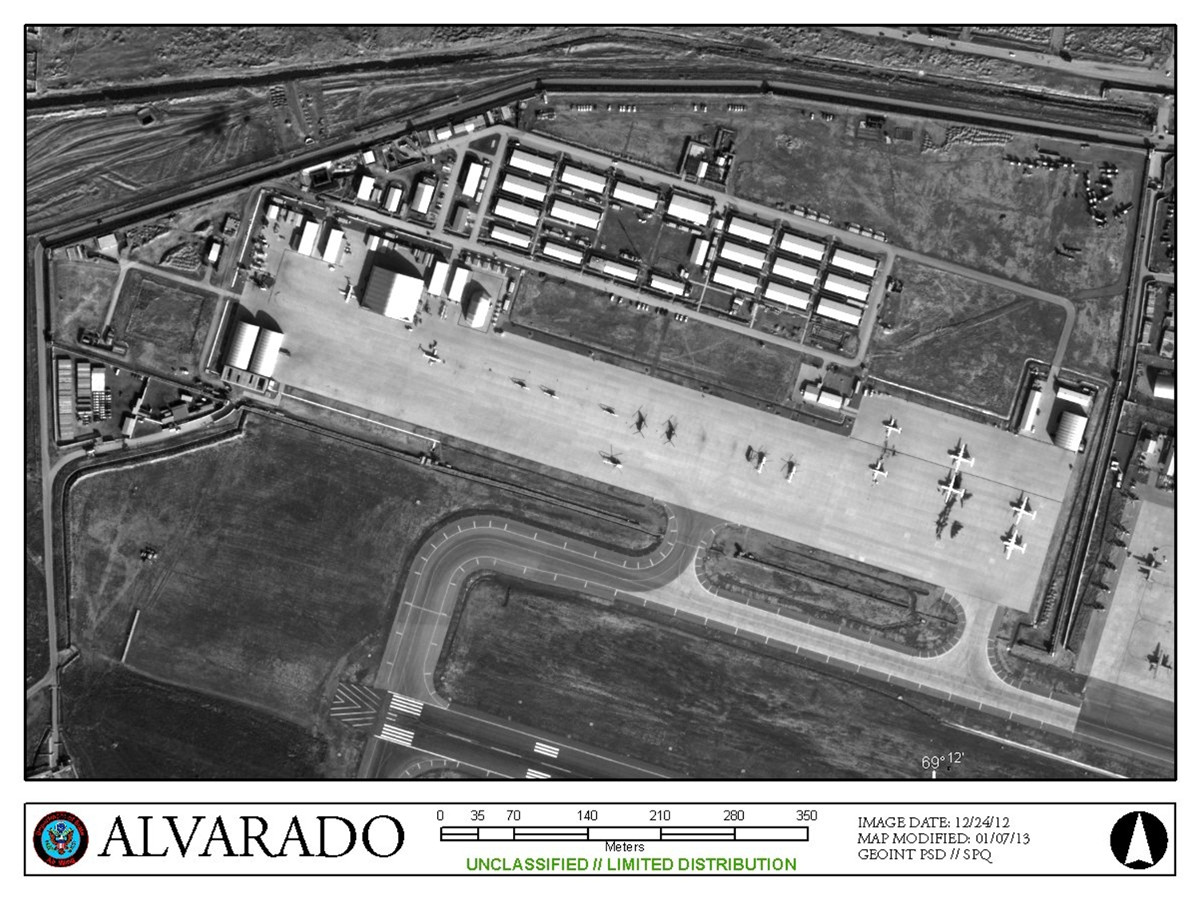

On Jan. 29, 2018, the Department of State’s Office of the Inspector General released the review of the Embassy Air Program, which is responsible for the flights, primarily using ex-U.S. Marine Corps CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters, to and from Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul, the U.S. Embassy in the city, and a nearby diplomatic support facility known as Camp Alvarado. Per the existing arrangement, intelligence analysts, private contractors working for private military company DynCorp, are supposed to help other personnel craft operational reports and flight plans that mitigate potential risks to those activities. At the time of writing, the Inspector General report was no longer available online, but it is unclear why that was the case.

“DynCorp intelligence analysts, however, do not have access to Top Secret intelligence,” the State Department’s internal investigators found in their audit. “In addition, the DynCorp intelligence analysts … are not located in facilities that are suitable for processing and storing of Top Secret intelligence.”

Those individuals do have a Secret clearance. As a result, they have relied heavily on information available through two separate U.S. government information networks, the Combined Enterprise Regional Information Exchange System (CENTRIXS) and the Secret Internet Protocol Routing Network (SIPRNet), which contain only information classified at the Secret level or below.

The concern is that since those analysts do not have access to Top Secret sources, such as the Defense Intelligence Agency’s Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communications System (JWICS), that they inherently lack the ability to present a complete picture of potential threats. Compounding that problem is that these individuals work in facilities that don’t meet the necessary security requirements for personnel to handle that information, even if it was available, such as having a specialized Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, or SCIF, on site.

The investigators did not say whether or not there was evidence that this lack of information had contributed to any dangerous incidents, but it’s a significant issue nonetheless. The Embassy Air Program runs an average of between five and six scheduled shuttle flights five or six times days a week, carrying an average of 150 people on each of those days, according to the State Department’s report.

In addition, the contractors are on call to help American diplomats, supporting personnel, and other U.S. nationals evacuate in a crisis and similar contingency missions, as well as otherwise being available to support the Ambassador and their staff. During the 2017 fiscal year, the Embassy Air Program in Afghanistan conducted more than 32,000 scheduled flights and more than 3,500 unspecified “special missions,” transporting nearly 36,000 passengers in the process.

Not having access to all of the U.S. government’s own intelligence resources can only increase the risks to those flights. Kabul has “tenuous security situations that are constantly changing, and often flying is the only safe way to transport personnel,” according to the State Department’s investigators.

The Office of the Inspector General report said that this same assessment of the general security environment and the concerns about contractors’ access to appropriate intelligence information applied to Embassy Air’s activities in Iraq, as well, which performs a similar volume of flights across that country. The State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs’ Office of Aviation, also known as the State Department Air Wing, has been managing the program in both countries since 2009, as well as aircraft elsewhere around the world engaged in counter-drug and other specialized activities.

The scope of the effort in Iraq is significantly larger than the one in Afghanistan, though, with helicopters running scheduled flights daily between the Embassy and other diplomatic sites in Baghdad. The shuttle service also makes trips to the cities of Erbil and Basrah, as well as Amman, the capital of neighboring Jordan, multiple times per week.

The Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs says it will make sure to require intelligence analysts working for Embassy Air in both countries have Top Secret clearances in its next round of contracts, which will cover more than a decade of future State Department Air Wing operations. The State Department is in the midst of that contracting process, but its not clear when properly cleared personnel might actually arrive. Officials are reportedly working with DynCorp to see if the company could reassign individuals with appropriate credentials to the jobs in the meantime, but that wouldn’t change the lack of secure facilities in both Afghanistan and Iraq for those individuals to actually view any Top Secret information.

At the same time, the report’s findings are especially pertinent to Afghanistan right now, where the Taliban has already made a number of uncharacteristically bold attacks on sites within Kabul in 2018. On Jan. 28, 2018, a member of the insurgent group detonated a suicide car bomb hidden inside an ambulance near the old site of the country’s Ministry of the Interior, an area that also contains a hospital and numerous diplomatic buildings, killing 95 people and injuring more than 190 others. This followed other notably deadly attacks earlier in the month, including separate incidents in which actual armed gunmen stormed the Intercontinental Hotel in the capital and the offices of Western charity Save the Children in the city of Jalalabad further East.

The situation in the country has already been increasingly precarious for some time. In September 2017, the Taliban claimed it had attempted to assassinate visiting U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis in a rocket and mortar attack on Hamid Karzai International Airport. America’s top defense official was never in any actual danger, but it was still a particularly brazen display of the group’s capabilities.

The fact that the State Department needs a private air force to safely travel in and around Kabul only underscores how dangerous the U.S. government believes the situation in Afghanistan is on the ground for its personnel. If effectively concedes that nowhere in the city of approximately five million people is it safe for Americans to be out on the street or even riding in discreetly armored vehicles.

Things may be even worse than they appear on the surface, too. On Jan. 30, 2018, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, or SIGAR, a Congressionally-mandated watchdog to oversee American military and other activities in the country, released its 38th quarterly report.

“This quarter, DOD [the Department of Defense] instructed SIGAR not to release to the public data on the number of districts, and the population living in them, controlled or influenced by the Afghan government or by the insurgents, or contested by both,” the watchdog said in press release to accompany the report. “This is the first time SIGAR has been specifically instructed not to release information marked ‘unclassified’ to the American taxpayer.”

The Pentagon has since confirmed it relayed this request to SIGAR, but has insisted that it is only the messenger, stating both that Afghanistan’s defense ministry asked for the redactions and that it has no authority to release NATO information, unclassified or otherwise. Afghan authorities have since denied they made any such demand and it is unclear why American officials could not secure approval from the North Atlantic Alliance for SIGAR to publish this information as it has done routinely in the past.

For the first time, the U.S.-backed coalition also asked SIGAR to remove details about casualties and other attrition, including desertion, as well as information about capability assessments regarding Afghan security forces, another critical metric for public accountability. The Pentagon again classified its own information on those topics, which it had first done in the previous quarter.

The U.S. military has in the past described Afghan casualty rates as “unsustainable.” We at the War Zone have also reported repeatedly on the continuing difficulties Afghanistan is having in trying to improve its security forces

and their capabilities, especially with regards to its Air Force.

Embassy Air’s operations, concern about growing risks to those activities, underscores how dangerous even some of the most heavily protected parts of Kabul, which is supposed to be the most secure city in the country, have become in recent months. A report by CBS News’ “60 Minutes” earlier in January 2018 said that private helicopters on contract to the U.S. government, including the State Department and the U.S. military, could actually be flying 10 trips or more in a day between the airport and sites within the city, keeping personnel safely ensconced behind blast walls and other defenses the entire time.

The security situation had deteriorated to that point that U.S. authorities had reportedly banned those personnel from making the two-mile long trips – as short as a five minute ride by air – via convoys on the ground. The video “60 Minutes” shot during their visit shows armed, contractor-operated State Department Air Wing Huey II helicopters flying patrols nearby, possibly escorting the flights. Embassy Air’s CH-46s do not carry weapons, but do have missile warning sensors and flare dispensers to ward off man-portable shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles.

“It’s a country at war,” U.S. Army General John Nicholson, who is in charge of all U.S. forces in the country and the NATO-led coalition, said in an interview for the segment. “And it’s a capital that is under attack by a determined enemy.”

Acknowledging that the capital itself is under regular attack is a relatively stunning admission on the part of the U.S. military, which has been actively fighting the Taliban and other insurgent and terrorist groups in the country since October 2001. Donald Trump is now the third American president to oversee the war and has approved yet another surge of troops and other support amid repeated promises to finally “win” the conflict.

“I don’t think we’re prepared to talk [to the Taliban] right now,” Trump while at the United Nations for a lunch with members of the Security Council on Jan. 29, 2018, dismissing the idea of any peace talks with the group in the near term. “We’re going to finish what we have to finish.”

That’s almost certainly to be easier said than done. In addition to the resurgent Taliban, the United States and its Afghan and international partners are also contending with ISIS franchise in the country and other threats. The Trump Administration has also taken a hard line against neighboring Pakistan, which U.S. officials and independent analysts have rightly noted at least tacitly provides safe havens to insurgents and terrorists, but is also essential for bringing the conflict to an end.

It remains to be seen whether that renewed political pressure will produce results. Pakistani authorities have threatened to cut off critical overland supply routes for the NATO-led coalition. They have also been unconfirmed reports of a growing push for a Pakistan-China-Iran regional bloc, which could present a political challenge to the United States.

It’s too soon to know for sure how the U.S. government’s latest strategy for the conflict will play out for sure. Unless the security situation dramatically improves soon, though, American diplomats and other personnel will be stuck making short hops in helicopters and staying within fortress like facilities.

Correction: An earlier version of this story said that the attack on Save the Children’s offices occurred in Kabul. This incident took place in the city of Jalalabad.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com