Boeing has launched a new push to promote a potential U.S. Air Force plan to re-engine its aging, but nevertheless very active fleet of B-52H Stratofortresses. New turbofans could significantly increase the bomber’s range and loiter capabilities, while reducing the overall cost per flight hours to operate the Cold War-era aircraft, but there have long been questions about where the money would come from and the overall complexities of such a conversion program.

On August 2, 2017, Boeing posted a slickly produced animated video to its YouTube channel outlining the various benefits. The nearly six minute long pitch contains information from five other, shorter clips on the company’s main B-52 website.

“Not only are new engines necessary, they will provide enormous economic benefits, creating billions of dollars of savings in sustainment and fuel over the remaining life of the aircraft,” the narrator explains. “Due to improvements in engine technology, a new engine installed today would not need to be overhauled ever for the projected life of the B-52.”

Boeing does not specify any particular engine in its presentation, but says that installing a modern type – almost assuredly a high-bypass turbofan of some kind – would give the B-52 40 percent more flying time with the same fuel load and that missions that presently require three tankers would only need two after the upgrades. In addition, the new jets would be quieter and more environmentally friendly over the existing Pratt & Whitney TF33, which have powered the H-models since they first entered service in 1961.

The TF33/JT3D design has been out of production for decades and the Air Force has had to develop its own specific shop at Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma to keep them going. With no ready supply of new spare parts, the basic costs associated with both routine and more serious maintenance have grown exponentially over the years.

According to Boeing, in 1996, it cost the Air Force $230,000 to overhaul just one of the engines. By 2016, it was approximately $2 million to rebuild the TF33s, which occurs at least once every 6,000 flight hours as a rule. All of this contributes to the cost for the Air Force to fly the B-52s, which is estimated to be more than $70,000 per flight hour, making it one the most expensive planes the service operates.

Though the Air Force has most recently been looking at a replacement scheme on and off since at least 2014, the issue came back into the public eye after a B-52 lost an engine in mid-air in January 2017. As The War Zone’s Tyler Rogoway wrote at the time, it was as if “the iconic bomber is literally begging for new engines,” adding:

The last time the USAF researched what it would need out of an engine program was 2014, when it concluded that new powerplants would need to save between 10-25% in fuel consumption, and would have to go 15-25 years before the first deep overhauls of the engines are required. The question of which engine would best fit this requirement remains, as well as whether four large engines or eight smaller ones (even six, under some concepts) would be best.

One area of concern is if new pylons would be needed to accommodate powerplants mounted in new locations under the BUFF’s wings. Such a requirement could result in a costly re-engineering of the B-52’s wings. With four larger engines, such as GE’s CF6 (called the F138 on the C-5M) or engines similar in size to the Pratt & Whitney PW2000 (the F117, in use aboard the C-17A) wing height and rudder authority for engine-out operations remain a question. As as result, costly flight control and avionics upgrades might be needed to accommodate their use, beyond the need for potential structural upgrades to the B-52’s wings.

With this in mind, probably the easiest option is eight compact high-bypass turbofans fitted to the aircraft’s existing pylons in re-contoured dual-nacelle pods. The Rolls Royce BR725 powering the Gulfstream 650 is one contender, as is GE’s Passport 20 found on the Global Express 7000 and 8000. If the Air Force decides to push forward with an official RFP for an engine swap on the B-52, other entrants will surely emerge.

The alternative to a new engine would be a more substantial rebuild program for the existing TF33s, which Pratt and Whitney has unsurprisingly been pushing for itself. However, Boeing specifically challenges the practicality of that plan in its video overview, suggesting that the cost savings would be minimal and likely wouldn’t address the fundamental obsolescence of the older powerplant’s existing design.

Though it doesn’t make engines, the Chicago-based plane maker has a clear incentive to advocate for a more significant upgrade package. One benefit of an uprated TF33 would be that it might not require significant modifications to the B-52’s engine pods or the pylons. As such, any such project might not ultimately involve Boeing.

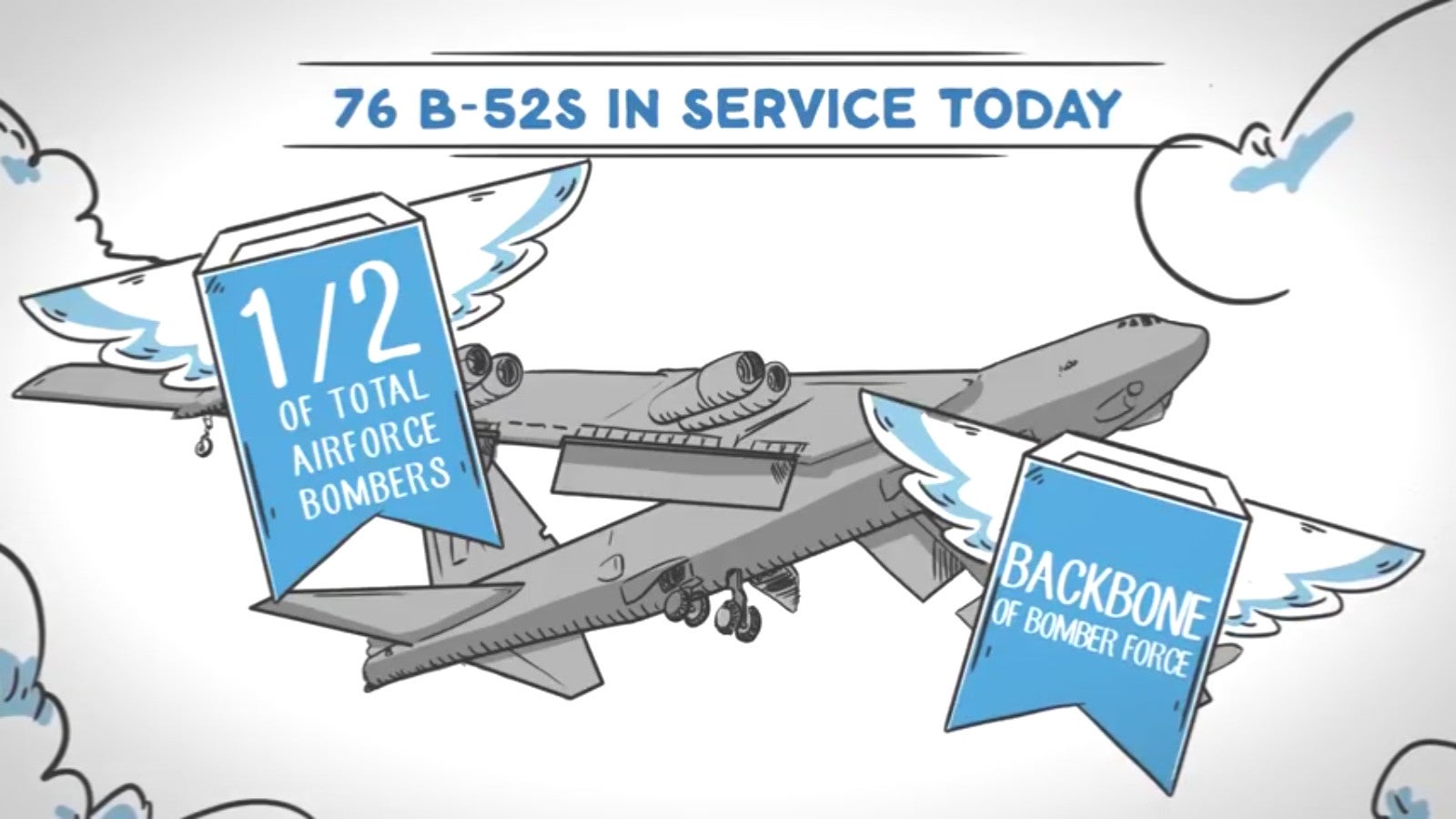

An entirely new jet engine could easily come along with a new mounting arrangement, letting Boeing tag-team with the engine-maker and share in the windfall of adding the powerplants to the Air Force’s 76 remaining B-52Hs. If the new configuration still includes eight separate turbofans, it would amount to more than 600 engines at least. The Air Force would definitely want spares on hand, as well. Even if the upgraded bombers only had four engines, this would be at least more than 300 units, plus additional ones in reserve. Whatever the case, there would be big money involved in any such project.

Of course, the Air Force has yet to make a decision on how it wants to proceed. It has long complained that budget cuts have limited its option for re-engining the B-52s. As a result, the service has suggested it could use a complicated public-private partnership, whereby whatever contractor or contractors they ultimately hire to do the work, whatever it entails, get “paid” out of funding freed up by the eventual cost savings. Such a mechanism could make the otherwise more expensive option of buying new engines more attractive since the up front would be relatively low.

In its budget request for the 2018 fiscal year, the service did include $10 million for a risk-reduction study into the issue, which could finally get things moving forward. With the Air Force expecting the B-52s to serve for at least another three decades, as both a conventional force multiplier and an important component of the country’s nuclear deterrent, its long been clear that something needs to be done about it’s dirty, gas-guzzling engines.

We’ll have to wait and see whether Boeing’s arguments have any impact on the service’s final decision.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com