Just a day after Turkey’s home-grown stealthy fighter aircraft was seen in full prior to its official rollout, yet another ambitious Turkish air combat aircraft has officially broken cover.

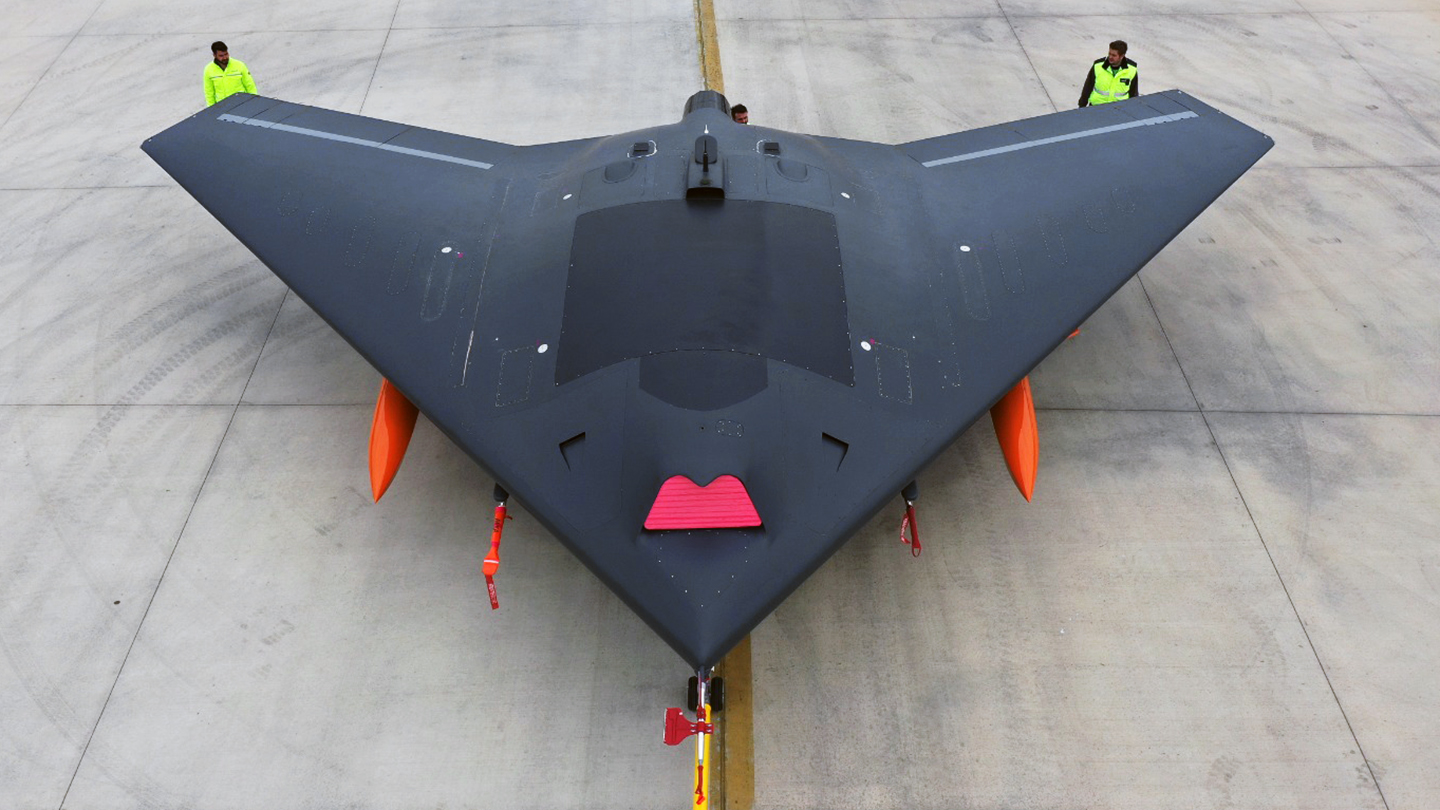

The Turkish Aircraft Industries (TAI) ANKA-3 MIUS (which stands for National Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle System in Turkish) is a low-observable flying wing unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV). The aircraft is roughly the size of a light fighter and is designed as a survivable, relatively long-endurance, strike, surveillance, and electronic warfare platform. Suppression and destruction of enemy air defenses are also said to be key intended roles for the ANKA-3. It’s thought that ANKA-3 is envisioned to work in conjunction with Turkey’s manned TF-X stealthy fighter for certain mission applications.

ANKA-3, which follows an increasingly diverse and advanced stable of Turkish drones, including the now famous Bayraktar TB2 family, features external hardpoints for munitions and fuel, as well internal weapons bays. It’s powered by a single turbofan engine.

Turkey’s Vice President Fuat Oktay stated the following about ANKA-3 in a budget-related speech in December of 2022:

“ANKA-3, with its jet engine and speed, high payload capacity, and tailless structure that is almost invisible on the radar, will open a new page in the field of UAVs. I hope we will continue to share the good news from our ANKA-3 MIUS project with our nation next year.”

It was reported recently that the type could begin test flights as soon as April, but it’s unclear exactly what the timetable for its maiden flight is at this time. We should expect taxi tests soon, regardless.

The aircraft features a serrated dorsal air intake, as well as an auxiliary intake to its upper rear, near its engine exhaust, which appears to be a conventional, round type. A small aerial and another conformal type antenna are seen on this auxiliary intake. Two large pitot tubes are seen installed along its leading edge, and another is seen extending from its nose. Generally speaking, this is not an uncommon test configuration for flying wing UCAV-type aircraft.

What looks to be a pair of fuel tanks or weapons shapes are seen under its wings. A large conformal rectangle fairing and a round one in front of it appear to be a different skin texture than the rest of the airframe. It’s unclear what exactly this is for but one possibility is that these are shrouds to cover antenna arrays. The planform overall is similar to Boeing’s X-45C and Dassault’s nEURon, although the overall aircraft is less refined.

We must state that perhaps more than other types of aircraft, stealthy flying wing drones are known to evolve through the testing process significantly. At first, low-observability is not essential to successful flight testing and other primary trials, so things like extra vents, antenna, pitot tubes, airframe surface refinement, and especially exhaust become far more refined in later iterations.

The exhaust, in particular, is among the hardest components of a low-observable aircraft to successfully realize, so a more basic exhaust can be used for initial testing. As predicted, we saw exactly this with Russia’s Hunter-B UCAV. A more production-representative configuration emerged after basic flight testing and other trials were complete, which included a low-observable exhaust, among many other refinements.

The big takeaway here is that Turkey is working on fielding a stealthy flying wing UCAV that puts more of a premium on low observability than high performance. The aircraft is an intriguing counterpart to the recently unveiled fighter-like Bayraktar Kizilelma drone that is already in flight testing.

These two types could provide an intriguing mix of advanced unmanned aerial combat capabilities to the Turkish Air Force, and potentially export customers, if they can prove their intended capabilities in testing. One is more of a high-performance concept with some low-observable features. The other design is less kinematic performance-minded, but its designers have put a premium put on survivability and persistence.

Currently, China and Russia both have fully disclosed active flying wing UCAV programs — the former has multiple types under development. The United States, on the other hand, has no such program declared as being under development. Instead, the focus has been on collaborative teaming aircraft that are mainly either highly cost-conscious or of higher performance. Industry has pointed to a more traditional UCAV as an option for the U.S. Air Force’s future unmanned air combat ecosystem, but there is no indication the service will take this route. Of course, we don’t know what is going on in the classified realm, but at this point, a traditional UCAV in that space would be problematic as it would only represent a research and development effort or a very low-density operational capability.

The reality is that the relevance of a flying wing UCAV was proven 20 years ago and looked to be the biggest revolution in aerial combat since stealth technology or even perhaps the jet engine. After it seemed like these aircraft would be a central fixture of the USAF’s near-term future, they totally disappeared from view. Even any mention of this class of unmanned aircraft was wiped from pretty much all of the USAF’s documentation and talking points. The U.S. Navy proceeded with the X-47B carrier-borne UCAV demonstrator tests, which were highly successful, but it too was puzzlingly abandoned. Instead, the Navy pursued a far less ambitious carrier-based unmanned tanker, the MQ-25 Stingray.

This absolutely bewildering situation — which has had huge impacts on force structure — and what it all really means was the focus of a 2016 War Zone expose you can read in full here. While the USAF may get a traditional UCAV in significant numbers in the future, it is easy to argue this is many years too late and that oversight has done serious damage to Pentagon’s air combat supremacy.

Regardless, Turkey clearly isn’t waiting around to realize its unmanned aircraft desires as it charges forward with its indigenous air combat aircraft initiatives. Yet another aircraft that was seen out on the tarmac at TAI’s plant in Ankara yesterday was the country’s new HÜRJET advanced jet trainer that can also provide light fighter capabilities. It is also intended to be Turkey’s first self-produced supersonic aircraft.

These four aircraft — TF-X, ANKA-3, Bayraktar Kizilelma, and HÜRJET — combined represent a new era of promise for Turkey’s aerospace industry and its air arm’s tactical capabilities. Fulfilling that promise is an entirely different story, though. All of these projects individually could be riddled with potential pitfalls. Major hurdles exist at every turn and it’s not just about the airframe. Software development and subsystem integration are among the biggest challenges. For the stealthy types, everything from low-probability of intercept sensors and advanced communications to radar absorbent coatings and all the processes that go with those factors, just to name a few, must be developed and realized on an operational level. Even reduced signature aircraft, not high-end low-observable ones, will have to overcome some of these issues. Access to engine technology is another potential issue. But if Turkey can turn these aircraft into real and relevant capabilities, it would be a massive accomplishment.

Still, what Turkey needs now is fully capable fighters, and it continues to pursue new F-16s, although Washington’s approval hasn’t flowed freely. This is due to a number of geopolitical factors, including Turkey’s sticking with its S-400 SAM system buy from Russia, a move that got it kicked out of the F-35 program. Getting fighters from Russia is a non-starter now and even if they could, the performance of Russian tactical aircraft in Ukraine has been so poor, it’s unlikely Turkey would want them. Making matters worse, the backlog of F-16 orders is substantial and could grow significantly larger in the near term. In the meantime, Turkey is extending the life of its F-16 fleet.

If F-16s can be had as a bridge, Turkey will have time to realize what would be a far more independent high-performance air combat inventory of the future. If that vision comes true it could come with considerable export success, as well.

Contact the author: tyler@thedrive.com