NASA’s Douglas DC-8 flying laboratory, one of only two examples of the airliner understood to still be flying in the United States, has ended its career. DC-8-72 N817NA, known to NASA as the Airborne Science Laboratory, made a final flight today out of the agency’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Palmdale, California, followed by a flyover of Ames Research Center, then on to its new home at Idaho State University.

Last month, NASA announced that the DC-8 had completed its final mission. N817NA returned to Armstrong Flight Research Center Building 703 on April 1, where it received a ceremonial water salute from the U.S. Air Force Plant 42 Fire Department. The final mission had been in support of the Airborne and Satellite Investigation of Asian Air Quality (ASIA-AQ) program.

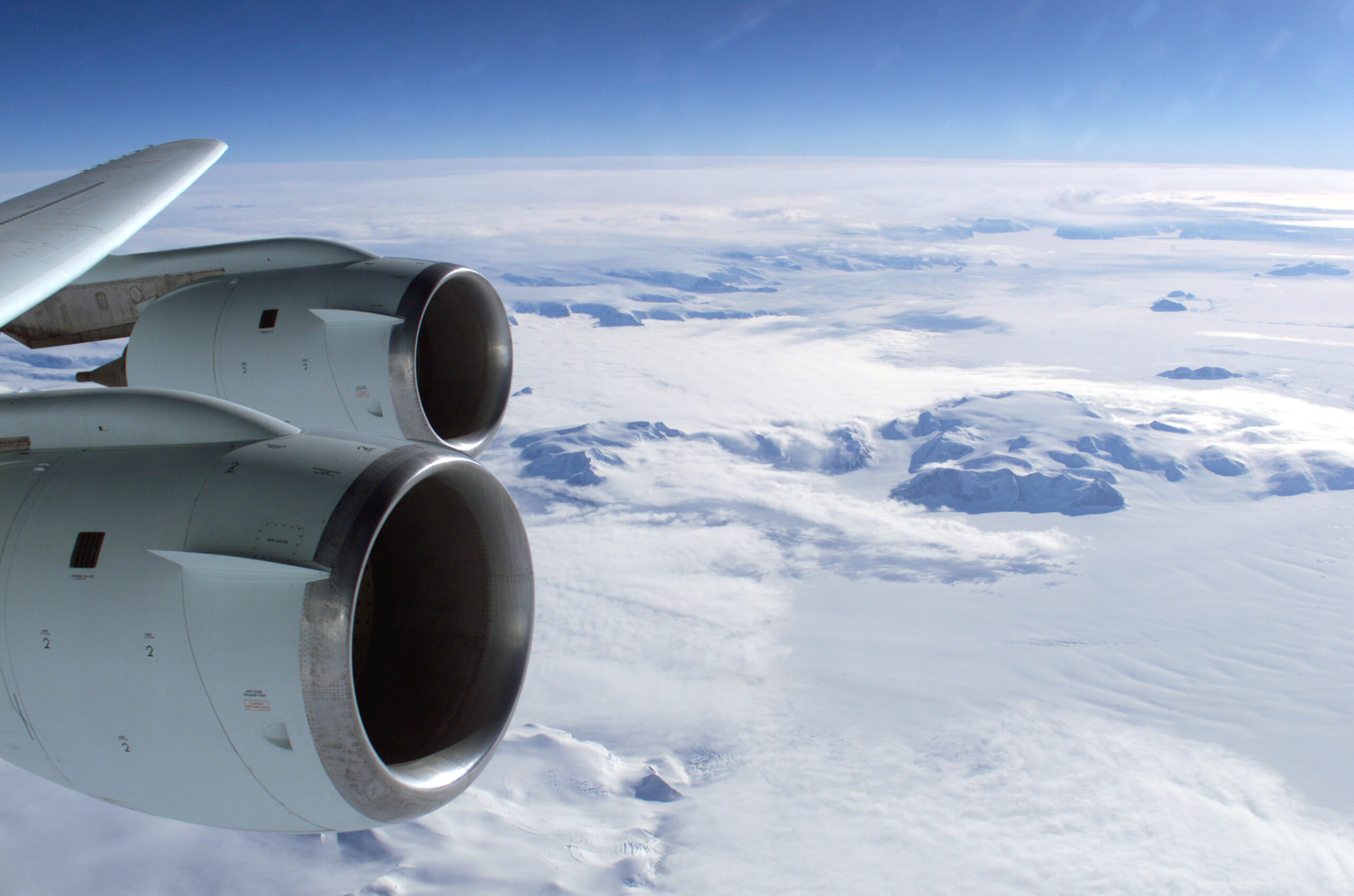

NASA described its DC-8 as “the largest flying science laboratory in the world.” The aircraft was acquired by the agency in 1985. It had been built in 1969 and previously served with Italian airline Alitalia, before moving to Braniff in 1979. The aircraft had been re-engined with CFM56 high-bypass turbofans, providing a considerable boost in terms of efficiency, which was leveraged on long-endurance missions.

After modifications, N817NA began operations in support of NASA’s Airborne Science mission in 1987.

In the process of its research work, the DC-8 supported federal, state, academic, and foreign scientists, collecting countless valuable data sets.

Four main types of research missions were carried out during its NASA career. These comprised sensor development, satellite sensor verification, telemetry data retrieval and optical tracking for space vehicle launch and re-entry, and research studies of the Earth’s surface and atmosphere.

As a sensor testbed, the DC-8 was used, for example, to verify prototype instruments intended for satellites, proving them in the Earth’s atmosphere before they were launched into space.

Once such sensors were in use on satellites, the DC-8 was then called upon to verify them, ensuring they were delivering the required accuracy. These missions involved the DC-8 flying under the path of a satellite’s path, using its own instruments to replicate the data collected by the satellite. The resulting information would then be compared for error.

Other space-related duties included using a specially installed tracking antenna in the DC-8’s nose to receive launch vehicle telemetry data, supporting both NASA and Missile Defense Agency programs. To monitor spacecraft re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere, the jet was equipped with optical tracking systems. These missions were also flown on behalf of foreign space agencies, including the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency.

However, the NASA DC-8 was perhaps best known for its Earth sciences missions, conducted as part of the agency’s Airborne Science Program. This took the aircraft to all continents on the globe, including flights over Antarctica that were launched from Chile, to study the polar ice field. The DC-8’s large payload capacity, 5,400-nautical-mile range, and onboard laboratory environment made it an ideal fit for this kind of long-haul research work.

The aircraft had seating for up to 45 researchers and flight crew and could carry 30,000 pounds of scientific instruments and equipment. The flight crew normally comprised two pilots, a flight engineer, and a navigator. Typical science missions lasted between six and 10 hours, although 12-hour missions were feasible.

With the growing threat from wildfires, the DC-8 was fitted with 32 sensors for a 2019 mission to investigate fires in the northwest and their effect on air quality. The campaign also involved satellites and other aircraft, including NASA’s high-altitude ER-2.

Looking around the aircraft, modifications for its scientific missions included various instrument ports, among them modified windows with mountings that could accept different instruments and probes. Other antenna mounts were fitted externally to the airframe, including on wing pylons. Optical windows were also provided around the aircraft, made of various materials. Sampling probes allowed air and aerosol samples to be taken in flight, while dropsondes would be deployed via a delivery tube.

Despite the age of the airframe, NASA’s DC-8 kept up with technological state of the art, for example adding a dual satellite communications capability, one each for the science team and the flight crew. The aircraft spent more than a year undergoing heavy maintenance in 2020–21.

However, in 2023, NASA finally acquired a successor for N817NA, purchasing a former Japan Airlines Boeing 777-200ER. The new jet has been undergoing modifications at NASA Langley Research Center including fitting new observation ports; power, data, and communications systems; and accommodation for instrument operators. The first operations with the new research aircraft are planned out of Langley in FY 2026.

Other signs of modernization in the NASA fleet include the recent retirement of its Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, or SOFIA, a kind of flying telescope housed in an adapted Boeing A 747SP, in 2022.

As for the DC-8, once at its new home at Idaho State University, it will be used to train future aircraft technicians by providing hands-on experience at the college’s Aircraft Maintenance Technology Program. It’s a fitting conclusion to a career that saw the aircraft fly airborne science missions with NASA for 37 years.

With the retirement of N817NA, it appears that the last DC-8 still active in the United States is the example flown by the humanitarian relief organization Samaritan’s Purse, as a cargo/passenger combi aircraft used to respond to crises around the world.

The Samaritan’s Purse DC-8 is now 51 years old and surely in the twilight of its service. Once it ceases flying, the illustrious career of the first-generation Douglas jetliner will come to an end in the United States. While it was overshadowed by the rival Boeing 707, the DC-8 was a classic of its time and enjoyed a long career, remaining in production until 1972 when superseded by wide-body airliners. Re-engining with CFM56 turbofans intended its use into the 1980s and 1990s, with the type latterly being used mainly as a freighter.

No more than a handful of DC-8s remain in use elsewhere around the world today and their active status is, for the most part, questionable.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com