The U.K. Ministry of Defense (MoD) has moved to provide reassurances after the failure of the Royal Navy’s latest Trident submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) test. However, this is now the second British Trident test in succession to go awry, and it provides further ammunition for critics of the U.K.’s hugely expensive nuclear deterrent.

The MoD has provided very few details of what happened during the latest test involving the nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) HMS Vanguard in the Atlantic on January 30. However, it admitted that an “anomaly occurred” during the drill but that it was “event specific.” The implication is that whatever went wrong would not have happened during a wartime scenario.

An MoD spokesperson said: “As a matter of national security, we cannot provide further information on this; however, we are confident that the anomaly was event specific, and therefore there are no implications for the reliability of the wider Trident missile systems and stockpile. The U.K.’s nuclear deterrent remains safe, secure, and effective.”

Added ignominy came from how news of the test failure first emerged, with a report in the tabloid newspaper The Sun.

The newspaper quoted an anonymous source who described the missile splashing down into the ocean immediately after launch: “It left the submarine, but it just went plop, right next to them.”

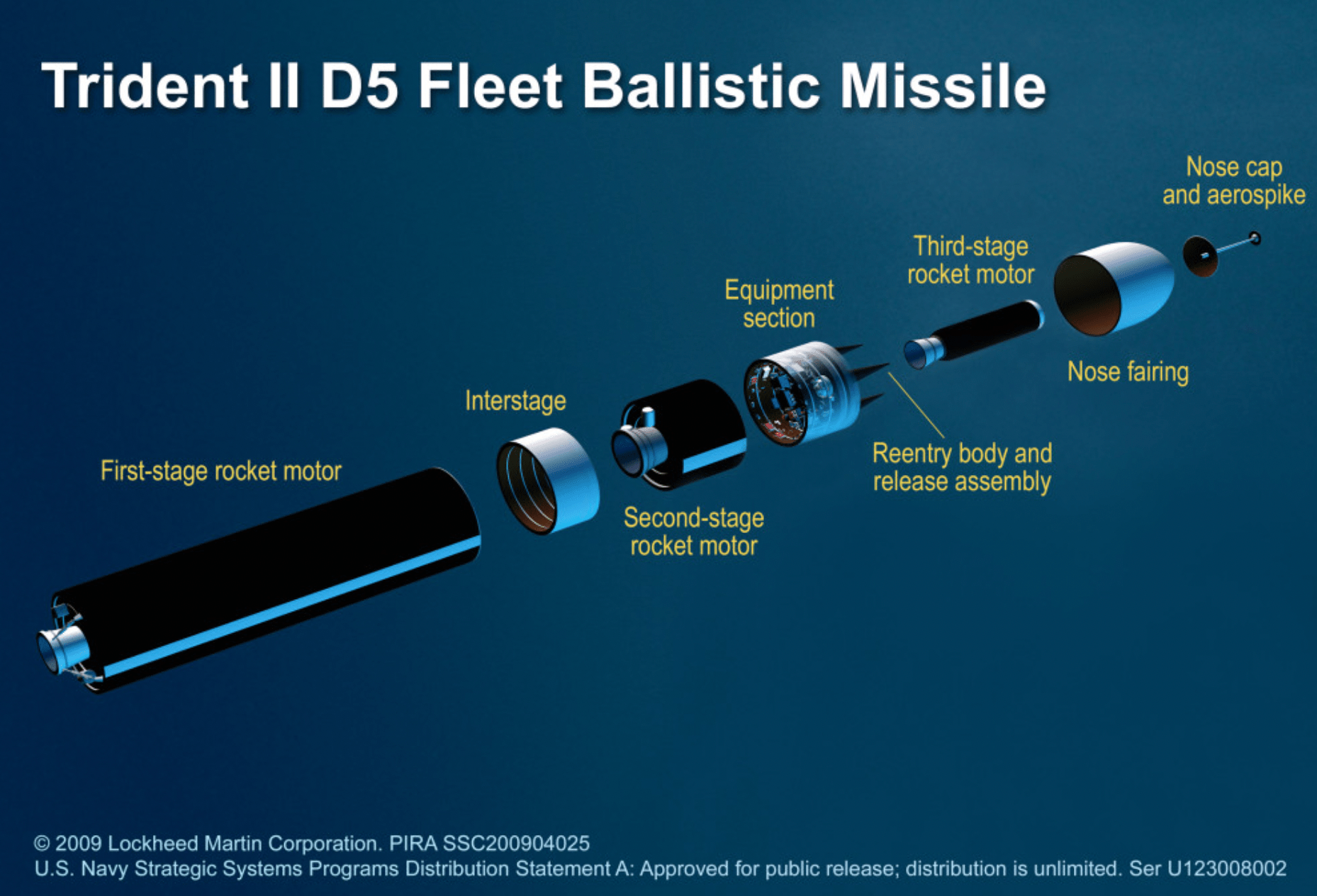

The same report said that the Trident missile had been successfully propelled into the air by the compressed gas in its launch tube but that the first-stage solid-fuel rocket motor failed to ignite.

The original plan was for the unarmed UGM-133A Trident II, or Trident D5 SLBM, to travel a distance of around 3,700 miles into the Atlantic, before coming down somewhere between Africa and Brazil. Reportedly, U.K. Secretary of State for Defense Grant Shapps attended the test launch and was aboard HMS Vanguard at the time.

As we have explained in the past:

Each Vanguard class boat has 16 missile tubes, but in practice, only eight are used, to comply with treaty regulations. A maximum of 40 warheads are currently carried on board the Royal Navy SSBNs when on deterrent patrol, each Trident missile being able to carry multiple warheads, or multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs). While each Trident can theoretically carry 14 MIRVs, depending on the type, 40 warheads on each patrol amount to approximately five per missile.

The story in The Sun forced the MoD to release a statement about the failed test, something it had apparently not planned to do.

Government ministers also rallied to insist that Trident remains trusted.

The Conservative Member of Parliament Tobias Ellwood, the former chair of the Defense Select Committee, said in a TV interview that the problem related to test equipment, rather than the Trident missile itself. “I understand it was some equipment that was actually attached to the missile itself that prevented the firing of the rocket system after the missile had left the submarine,” Ellwood said.

Meanwhile, the shadow defense secretary, John Healey, of the Labour Party, said: “Reports of a Trident test failure are concerning. The defense secretary will want to reassure parliament that this test has no impact on the effectiveness of the U.K.’s deterrent operations.”

Undoubtedly, launching an SLBM from a submarine is a complex process and failures are by no means uncommon.

The fact that this was the second test of its kind to fail sequentially adds to the embarrassment, however.

Back in June 2016, another British Trident launch in the Atlantic was a spectacular and controversial failure, with the unarmed missile reportedly flying off course in the complete opposite direction, instead heading toward the United States mainland. Its self-destruct feature had to be triggered, ensuring it blew up in midair over the water.

Since then, the British-owned Trident missiles have undergone a life-extension program, which ought to have made them more reliable.

Also troubling in terms of the latest failure is the fact that this was intended as a final pre-deployment exercise for HMS Vanguard after more than seven years spent in refit.

An MoD spokesperson said: “HMS Vanguard and her crew have been proven fully capable of operating the U.K.’s continuous at-sea deterrent, passing all tests during a recent demonstration and shakedown operation, a routine test to confirm that the submarine can return to service following deep maintenance work. The test has reaffirmed the effectiveness of the U.K.’s nuclear deterrent, in which we have absolute confidence.”

For the crew of HMS Vanguard, the missile failure and the resulting media scrutiny would hardly have been welcome. This also comes at a time when Royal Navy SSBN crews are likely under higher levels of stress due to prolonged periods at sea.

The U.K.’s continuous at-sea deterrent involves the four boats of the Vanguard class, which began to enter service in 1994. One of these SSBNs is at sea at all times.

Last year, a Vanguard class boat returned from a patrol of around six months — potentially a record-breaking length of time. Extended deployments for Royal Navy SSBNs have led to questions in the past in terms of operational safety. Back in December 2022, The Guardian newspaper reported that Vanguard subs had been deployed at sea for what were then record-breaking lengths of five months each that year.

“The great danger is that this unchanging routine, week after week, leads to boredom, complacency, and an inevitable drop-off in standards,” Rob Forsyth, a former Polaris SSBN commander wrote at the time. “Just as worryingly, personal relationships are tested to the limit.”

Since 1998, the Royal Navy’s SSBNs have provided the U.K.’s sole nuclear weapons capability, although the latest failure has prompted discussion about whether there’s an argument for the U.K. Royal Air Force having its nuclear strike role reinstated.

That seems highly unlikely, especially with the United Kingdom committed to replacing the Vanguard class with four new Dreadnought class boats, the submarines alone costing around $43 billion. These boats are expected to enter Royal Navy service in the early 2030s. The new SSBNs will also be armed with modernized Trident missiles, which will likely receive W93 warheads.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has unveiled a new defense policy that includes potentially using its submarine-based nuclear deterrent in response to not only threats presented by weapons of mass destruction but also by other threats from “emerging technologies,” as you can read about here. While the specifics of those kinds of threats are unclear, it may well also tie in with plans to increase the upper limit on U.K. warhead numbers, another development that The War Zone has previously discussed.

Recapitalizing the U.K.’s SSBN fleet and the SLBMs that arm it is a controversial endeavor, to say the least. There is a long-standing question about the relevance of this kind of nuclear deterrence, and its value for money, exacerbated by budget constraints that are being felt across the U.K. Armed Forces.

While the failure of two successive Trident missile tests may be simply an unhappy coincidence, it will be the last thing that the U.K. Ministry of Defense wants as it tries to justify the costs of the forthcoming Dreadnought class submarines.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com