Flint was nervous. It was early on the morning of March 21 at the Dnipro airport and he and a small group of fellow soldiers from the Ukraine Defense Intelligence Directorate (GUR) were about to embark on a secret and dangerous mission, one of the most important of the war.

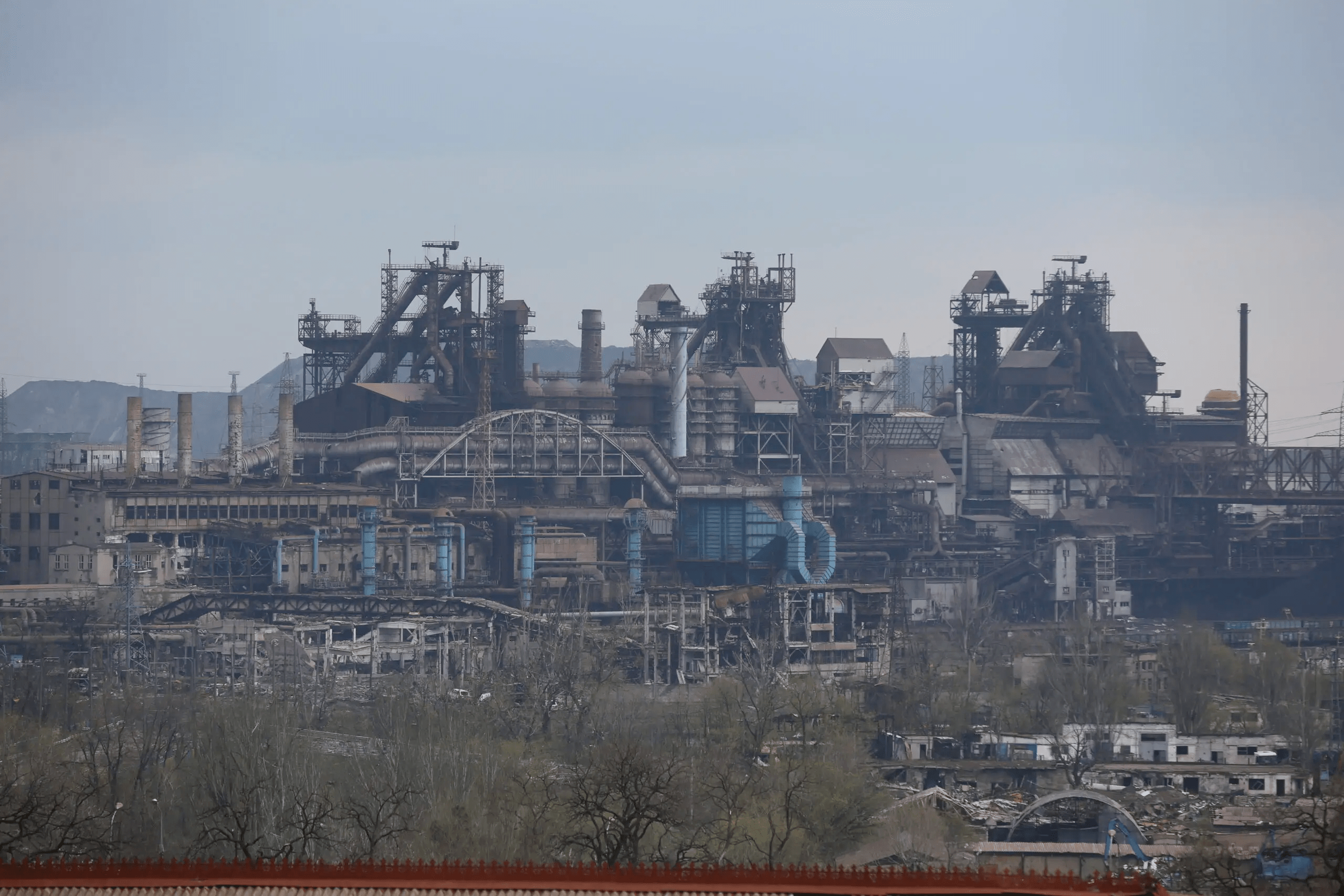

For weeks, the defenders of the Azovstal steel plant in the port city of Mariupol on the Sea of Azov had been under siege by Russian forces. They were running low on ammunition, food, and medical supplies and the numbers of badly wounded rose daily.

The plan, cooked up by Maj. Gen. Kyrylo Budanov, the head of the Defense Intelligence directorate, was audacious and potentially disastrous. Fly some of the dwindling numbers of Ukraine’s operable helicopters 60 miles over enemy territory heavily defended by Russian ground-based air defenses and fighters, land inside one of the most intensely bombarded patches of Ukraine, drop off supplies, and fly to safety with those in need of immediate medical care.

“The importance of this flight was the fact that a lot of people looked at this operation as an impossible one, so we wanted to show other pilots and troops that it was possible,” the GUR soldier told The War Zone Monday morning in an exclusive interview. Speaking on condition that we only use his callsign – Flint – he shared never-before-told details of what Ukraine officials now laud as a highly successful operation that helped the defenders of Azovstal keep fighting and pin down Russian troops at a critical juncture in the defense of Ukraine.

Flint was fully aware of the danger.

“We understood that it was a one-way flight,” he told The War Zone, speaking through an interpreter. “And we were ready to the fact that we will not return back.”

So he and the other troops changed into civilian clothes and boarded two Mi-8 Hip helicopters that were stripped of armaments and other systems to reduce their weight. This was done to make room for the load of Stinger shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles, NLAW anti-tank missiles, and Starlink communications systems that would allow the Azovstal defenders to stay in the fight and in touch.

Flint said he had a ‘Sophie’s choice’ of places to sit: near the fuel tank, which would kill him instantly if it was hit, or on top of boxes of ammunition, in which he would merely break some limbs if the helo crashed.

Around 3:30 AM, they lifted off, first headed for a refueling stop, then for the 60-mile hop across Russian-controlled territory to the steel plant surrounded by the Russian 8th Army.

There were two main concerns, said Flint. The first was Russian air defenses, particularly man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) and Tor self-propelled surface-to-air missile systems. The other was keeping the mission a secret.

But once on board, the nervousness faded. There were Ukrainian forces in desperate need of help. So Flint, sitting atop the ammo boxes, settled in for the low-level flight that would see the Hips zip along at about 150 miles per hour, hugging the ground at an altitude of about 15 feet to avoid enemy radar.

“I just concentrated on our mission,” he said.

Mission Delayed

In what would be the first of seven such missions involving 16 Hips, the first helicopter resupply flight to Azovstal was supposed to take place two days earlier.

But thanks to security concerns and ever-evolving intelligence reports about the location of Russian air defenses, it was delayed, Flint said.

“We postponed this because of the fact that we knew that the adversary had information that we planned to do something and we saw the big concentration of adversary aviation over the territory of the Azovstal plant,” he said.

There were a lot of people involved in the operation and congregated at the airfield. Technicians. Refueling personnel. Police.

“It was really observable that so many people were on the airfield,” he said. “That’s why we postponed this operation three times.”

So the decision was made to launch an elaborate disinformation operation to throw off the Russians.

One soldier called his wife and told her that he will soon be home because the operation was denied by the chain of command. Flint said he too had a conversation with someone, telling them that the mission was scrubbed.

“When we returned to the airfield, we loaded on the helicopter and flew away and in such a way we denied the information flowing in case we had any like an adversary spy or something like that,” he said. “It was a big surprise to everyone.”

There were other problems.

Once read into the mission, several pilots opted to sit it out, Flint said.

“Some of them refused to do this because they thought that it’s impossible,” he said.

But the first pilot to sign on had a deep personal reason.

“The main reason he agreed to do it was the fact that his wife was a combat medic at Azovstal. She worked with heavily wounded soldiers and the main idea during the first flight was to evacuate heavily wounded soldiers and also her from the territory of the plant.”

Risky Business

Getting to Azovstal was no easy task.

Flying fast and low over changing terrain with mountains and obstacles like trees and telephone wires required a great deal of pilot skill.

In some cases without any guns to defend themselves, “we were flying naked,” said Flint. And not all pilots were trained to fly using night vision equipment, requiring some missions, like the one Flint was on, to fly partly in the daylight.

The combination of factors, he said, is why the soldiers donned civvies and left all their military identifications behind.

“In case, after being shot down, you survive, according to the plan we had to be in civilian clothes to try and move into territory under the control of the Ukrainian government,” he said.

After a quick refueling stop in Ukraine-held territory somewhere right up on the line of contact, the two-ship flight took full advantage of the element of surprise and buzzed unscathed over Russian-held territory until they were over the cratered steel plant.

Looking down, the pilots found a small plot of surface, uncluttered by debris and just big enough to land.

The Hips settled down near the entrance to some of the underground tunnels through which the defenders hid, shot, moved, and communicated.

“Avostal was almost completely destroyed,” said Flint. “The same as Mariupol city.”

Landing, however, turned out to be the easy part.

For the next 15 to 20 minutes, the troops unloaded the supplies and gathered up the wounded, about 16 of which arrived via GAZ-66 trucks emerging from the tunnels.

The pilots, meanwhile, kept the engines running and the blades whirling.

“All this time we were within the sector of adversary aviation activity,” said Flint. “That’s why we had to be ready for any changes in the situation. And we were not supported by any support aircraft.”

After they landed, some of the Azovstal defenders expressed surprise.

“They said that ‘we don’t know the point of your departure, but you flew to us from the sky.’” Flint recalled.

As the men from the Hips dropped off the Stingers, NLAWs, and Starlink systems, and loaded up the wounded, the Azov battalion troops “understood they had to cover our departure,” said Flint. “They tried to involve the adversary as much as possible into a battle. They fired in order to provide us cover.”

As the Hips took off, loaded with the wounded, all hell was breaking loose down below.

“There was really tough fighting between our troops and the adversary troops,” said Flint.

Departing low, again to try to avoid triggering Russian air defenses, the Hips once again made it back to the refueling point without taking fire. They returned safely to Dnipro around 7:30 AM.

“It’s absolutely special emotions when you hand over the wounded to the doctors and you understand that you did something that’s totally impossible,” Flint recalled his emotional state upon landing. “You feel proud and happiness about your people.”

But subsequent flights became increasingly difficult, said Flint, as the Russians began to catch on and the air defenses began to thicken.

“During the second flight, the helicopter was fired on but was able to reach the refueling point and he finished its landing successfully,” said Flint.

To counter the Russian defenses, pilots changed routes, sometimes flying over land, sometimes over water.

“I know about the situation where our helicopter flew between two Russian ships and then turned to the right and moved above the sea to the territory of Ukraine,” he said.

There was also at least one flight – which unlike the rest consisted of four Hips, not two – that was accompanied by an Mi-24 Hind serving as a fire support helicopter. During that mission, more than three dozen wounded were evacuated.

In a previous interview, Budanov told The War Zone that three helicopters were shot down – two on the resupply mission and one coming to the rescue.

Officially, Flint said that there is only one helicopter listed as destroyed, with two others considered missing.

End of Mission

Before they ended, the helicopter flights didn’t just deliver supplies, but also Azov Regiment members wanting to reinforce the troops burrowed into the steel plant. Eventually, though, the sorties to Azovstal stopped, with the last ones occurring sometime around the middle of May.

Deputy Chief of the Main Operational Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Oleksiy Hromov, previously said that the deliveries were stopped because “information about the aid was disseminated. As a result, the enemy took measures to strengthen the air defense system, which made it difficult for us to carry out such actions and led to the loss of personnel and helicopters that evacuated the wounded.”

Flint said he doesn’t know exactly when they stopped, or why, but he has an idea.

“Almost each meter of the landing zones that could be used by our helicopters was under constant fire from the side of the adversary,” he said, adding that one of the last flights he knows about took place sometime around May 10.

By May 20, the last of more than 2,000 Azovstal defenders surrendered. Interviews with the prisoners, according to one report, stated that the Azov fighters had been “beaten, tortured with pliers, electrocuted and strangled.” CBS News on Monday reported that Russia began turning over bodies of Ukrainian troops killed at the plant.

Flint, who has since been on other secret missions for Ukraine that he can’t talk about, told The War Zone that he has stayed in touch with some of the wounded he helped rescue.

“Unfortunately, not all of these people were able to preserve their health in the same condition that they had before,” he said.

Recently, he even met up with several Azovstal defenders he helped rescue.

“One guy was 20,” said Flint. “He was without a leg.”

The young man was wearing sunglasses, given to him by his girlfriend.

“She said, ‘that with these glasses I’m looking like Brad Pitt,’” Flint said the amputee soldier told him.

“That’s why I am happy that I’ve met such great guys.”

Flint said that, “personally, I’m really proud that I participated in such operation and in some other operations I’m not able to talk about now.”

In the future, people will learn from these resupply operations, for which Flint credited Budanov and President Volodymyr Zelensky for approving.

“We will have to write about these operations in books and not only in books, but also we have to make movies about this last place of defense in Mariupol,” said Flint. “And I think that this story will be retold by our children, about this heroic situation there.”

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com