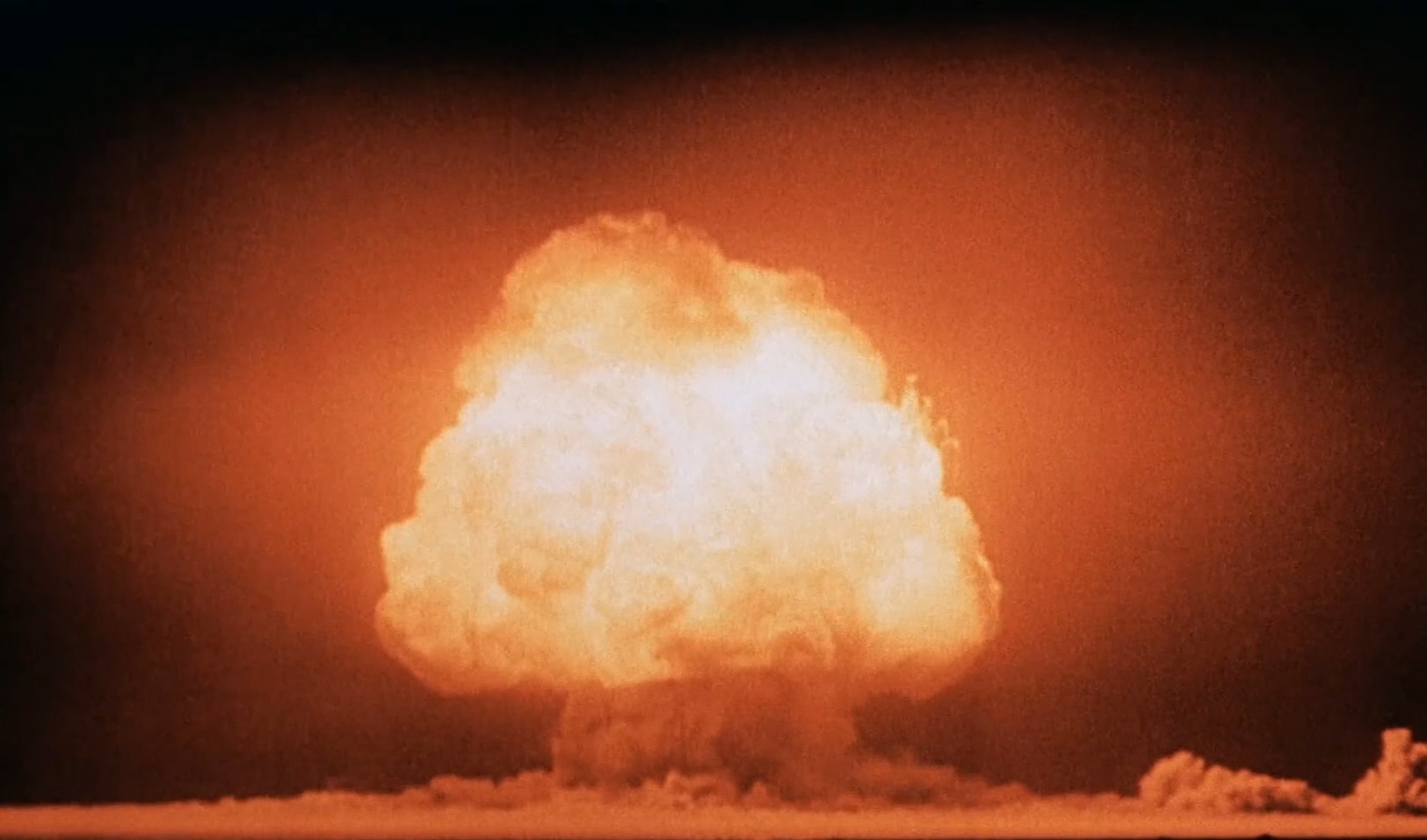

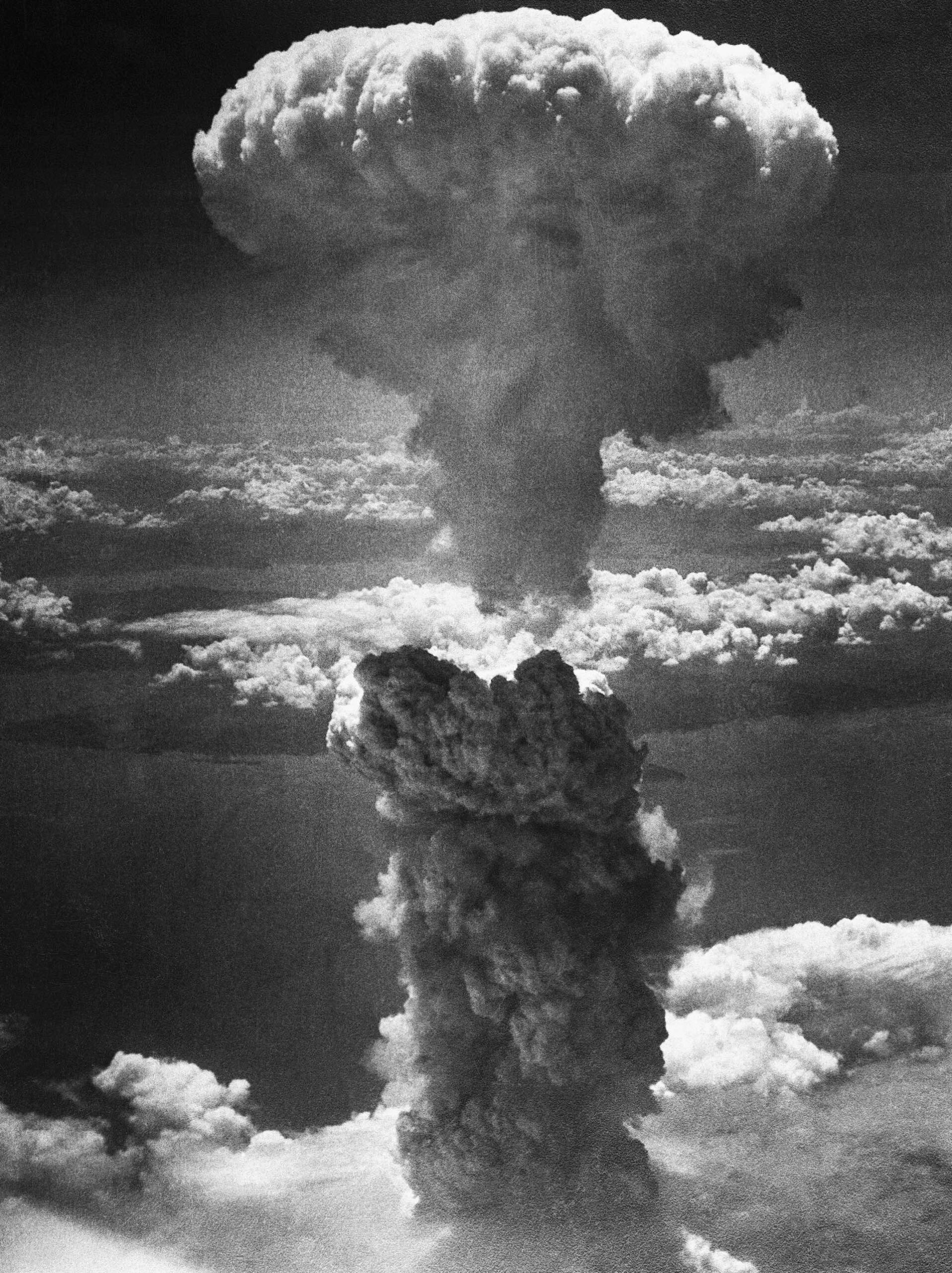

The mushroom clouds pictured following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 are among the most recognizable images taken in history. Yet the visual documentation of the only uses of atomic weapons in armed conflict has an intriguing history all of its own. As it turns out, the famous imagery was actually the product of good luck rather than the result of successful planning. In fact, the iconic visuals of the mushroom clouds, recognizable to so many, were almost never captured at all.

@atomicarchive on Twitter, who has a new YouTube channel that is dedicated to the history of nuclear weapons development in the Twentieth Century, has produced a fascinating and highly-detailed video on the subject. The video outlines the history of how the visuals were captured of the atomic bomb attacks on Japan, and how the actions of certain individuals, as well as bizarre series of events, were instrumental to this.

You can and should watch the full video below:

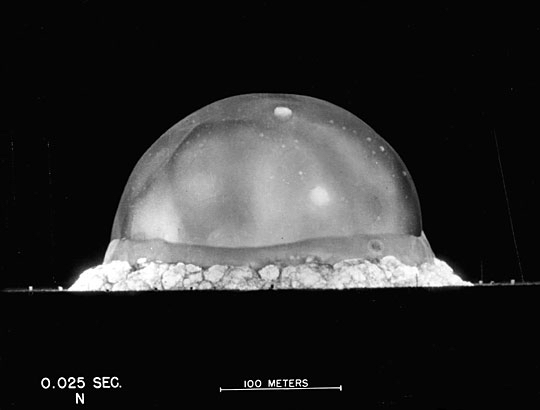

Of course, techniques for capturing nuclear explosions predated the bombing of Hiroshima. On July 16, 1945, state-of-the-art motion and still cameras were used to document the first-ever nuclear weapons test – code-named ‘Trinity’ – which took place in the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico. Fastax 16mm fast-speed cameras, capable of recording at 10,000 frames per second, were used. It was expected that similar equipment would be used for recording the bombings of Japan.

Fast forward to August 6, 1945, when three American B-29 Superfortress bombers took off from Tinian Island in the Northern Marianas for Hiroshima. One of those bombers, “Necessary Evil,” was kitted out to capture the explosion.

Unlike at Trinity, however, “Necessary Evil’s” Fastax camera failed and it appears as if only one of these cameras was aboard the aircraft, to begin with. Other cameras installed on “Necessary Evil” also failed to capture anything. As @atomicarchive’s video highlights, there are several theories as to why the aircraft’s camera equipment failed. One theory is that the camera operator, Bernard Waldman, forgot to open the Fastax’s shutter before the blast. Another one suggests that Waldman did manage to capture the blast, but that the film was later damaged or destroyed at the Tinian base photography lab. A third posits that an electromagnetic pulse from the bomb interfered with the timing of the camera.

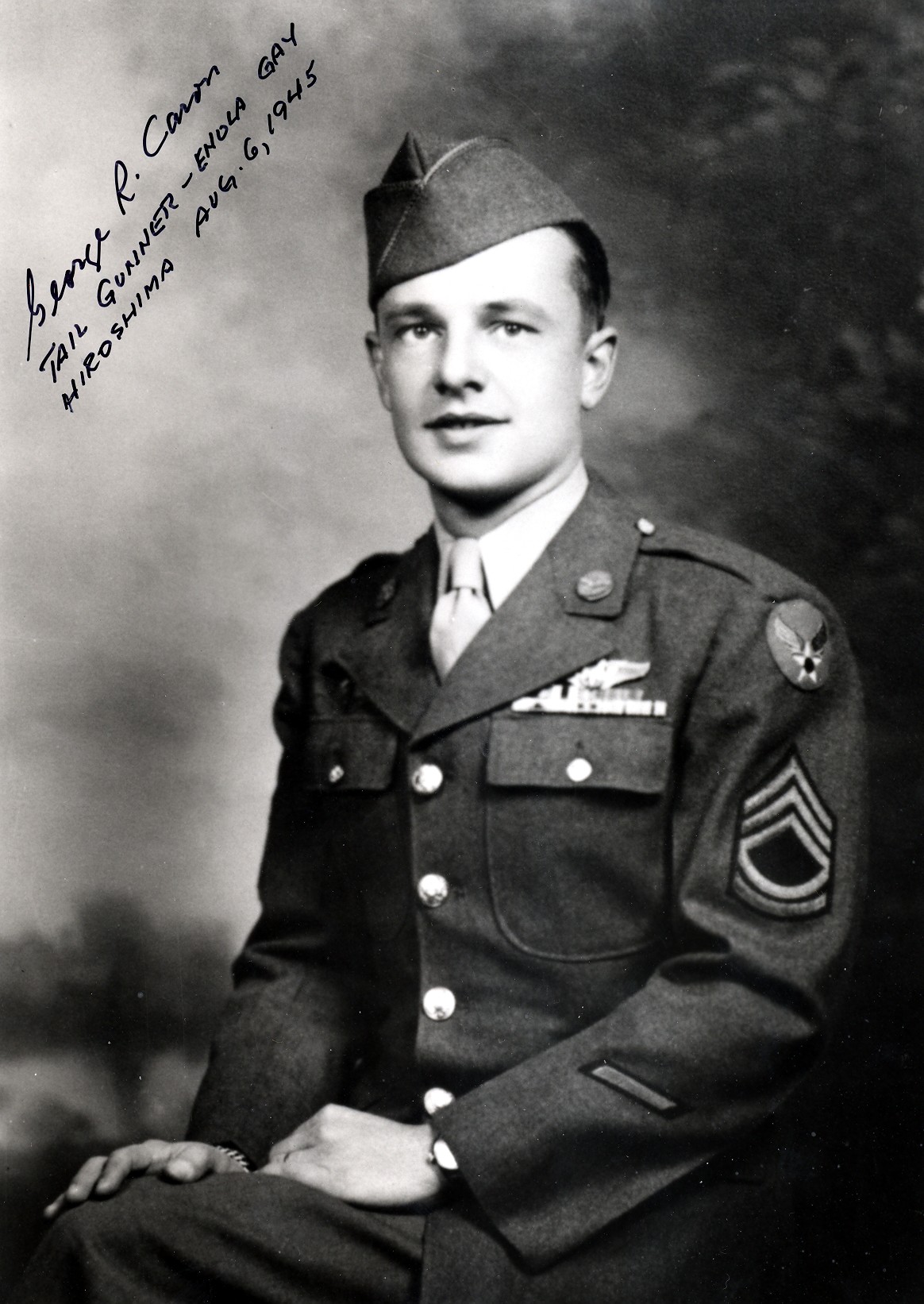

George “Bob” Caron, the tail gunner of “Enola Gay” – the B-29 which dropped the nuclear bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” on Hiroshima – was the only individual able to take any official photos of the blast, according to the video. Remarkably, this was because Caron brought a hand-held Fairchild K20 camera with him on the instructions of Jerome Ossip, the 509th Composite Group’s photography officer. The first to see the fireball and the mushroom cloud, Caron was able to take several images when the plane turned after the bomb detonated.

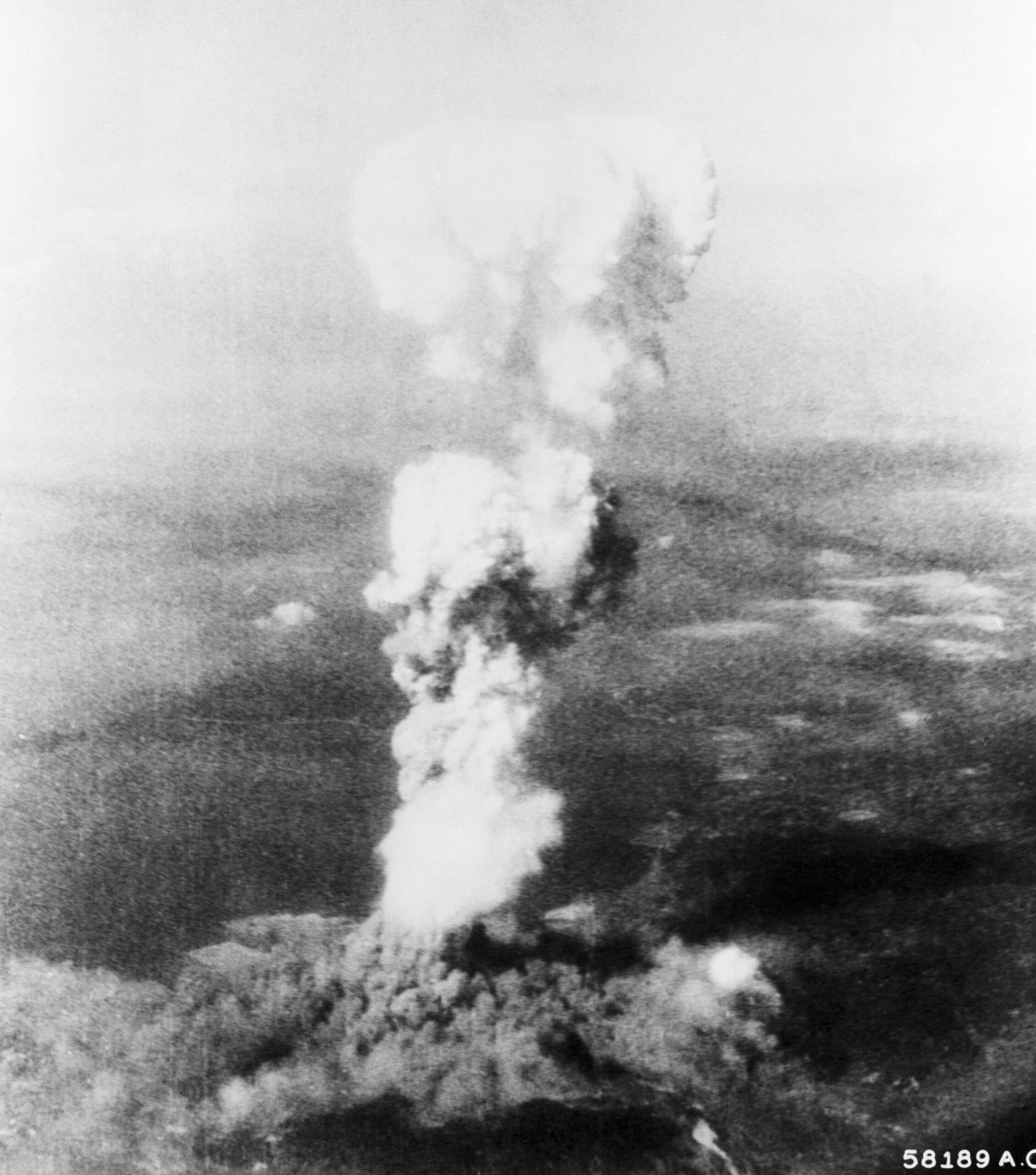

Other images and footage were taken of the blast, some of which were not seen until decades after the event. Harold Agnew, who flew aboard another B-29, “The Great Artiste” – the instrumentation aircraft that dropped canisters to record the bomb’s yield – supposedly took the only known footage from Hiroshima with his own personal camera (other sources suggest Agnew gave his camera to another crew member). Moreover, Russell Gackenbach, the navigator on “Necessary Evil,” captured an image of the mushroom cloud roughly one minute after the explosion on his own Agfa 620 camera. This image, seen below, was not released publicly until 2014.

That any images of the Nagasaki bombing were captured was even more surprising. Three B-29s took off from Tinian Island for Kokura – the primary target of the second atomic bombing mission – on August 9, 1945. “Bockscar” carried the “Fat Man” atomic bomb, “The Great Artiste” carried blast measuring instrumentation, while “Big Stink” served as the photography aircraft.

Two critical issues arose for “Big Stink” on August 9.

For one, the main camera operator, the physicist Robert Serber, was kicked off the aircraft before takeoff. As “Big Stink” was taxiing to the runway, Serber found that prior to boarding the aircraft he had been given an extra life raft instead of a parachute. Although he tried to obtain a parachute, Maj. James Hopkins, the pilot of “Big Stink,” ordered him off the aircraft at the end of the runway.

In his postwar memoirs, Serber mused that Hopkins’ decision was “truly idiotic,” owing to the fact that Serber was the only person on the aircraft who could work the camera. Although Col. Paul Tibbets – who was the pilot of “Enola Gay” during the Hiroshima bombing – demanded that Hopkins allow Serber to instruct another crew member on how to operate the camera over the aircraft’s radio, the camera was still too complicated to operate without Serber present, and was therefore not used.

Second, when Nagasaki was selected as the fallback target location over Kokura due to cloud coverage, “Big Stink” failed to rendezvous with the other B-29s at the right location in time to document the bombing.

Despite this, a greater number of photos were taken of the Nagasaki blast compared to Hiroshima. Perhaps the most recognizable was captured by Lt. Charles Levy, the bombardier of “The Great Artiste.” Levy’s image was taken with his own personal camera. Moreover, footage of the Nagasaki explosion was obtained due to the actions of Harold Agnew. According to the video, Agnew provided filming equipment to Walter Goodman, an engineer on “The Great Artiste,” and Albert DeHart, “Bockscar’s” tail gunner, with instructions to film the bombing.

The force of the blasts unleashed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were enormous. It’s been estimated that they were equivalent to the explosive force of 13 kilotons and 21 kilotons of TNT, respectively. Yet the fact that we have any surviving visuals of them from the air is really remarkable in and of itself considering all that went wrong in trying to capture them.

Thanks to @atomicarchive for taking the time to research this surprising history and make sure to watch the video for the complete story.

Contact the author: oliver@thewarzone.com