In 1977, with the Cold War in full swing, the U.K. Royal Navy’s nuclear-powered attack submarine HMS Swiftsure (S-126) slipped right into the heart of a large-scale Soviet Northern Fleet exercise in the Barents Sea. The British submarine penetrated undetected through the layered escort screens of destroyers and frigates and meticulously approached the Russian aircraft carrier Kiev. The submarine recorded extremely valuable acoustic signatures and took incredible underwater periscope pictures of the Soviet carrier’s hull and propellers. As an example of a perfect covert operation, the Soviet Navy had absolutely no idea about the presence of the NATO attack submarine and the amount of valuable data it was able to collect.

The hunter

The origins of the Swiftsure class of nuclear submarine can be traced back to the mid-1960s. At the time, the Royal Navy was facing the growing threat of nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed Soviet submarines routinely operating in the Atlantic Ocean. To counter these, the Swiftsure included improvements based on the lessons learned from previous all-British-designed classes, allowing for deeper diving, higher speeds, and lower radiated noise.

Powered by a single PWR Mk 1 nuclear reactor and an auxiliary Paxman Ventura diesel generator, submarines of this class were armed with five 533mm torpedo tubes capable of launching Mk 24 Mod 2 Tigerfish and later Spearfish heavyweight torpedoes, and Stonefish/Sea Urchin naval mines. UGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles and UGM-109E Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM-E) Block IV were subsequently added to the armory.

The previous British Valiant and Churchill classes of SSN had included raft-mounted machinery to isolate mechanical and electrical sources of noise and vibrations from the hull and reduce the overall radiated noise of the submarine. Three different propulsion modes — High, Moderate, and Low — meant that the rafts were locked at high speeds (evasion maneuvers, target interception, etc.) with no noise reduction, but at low and moderate speeds the rafts isolated the machinery (turbines, generators, pumps, etc.) from the hull. For very low, or ‘creep’ speeds, an electric motor was used and there was also a small retractable motor used in case of main propulsion loss. The design changes utilized on the Swiftsure class included rafts that were further improved, with the high-speed locking mechanism no longer required.

Another exotic feature of the class was the introduction of pump-jet propulsion. This type of propulsion, back then relatively new but now common across almost all new submarine classes, offers several advantages over the standard propeller in many naval combat scenarios. The benefits include quieter propulsion at the same speed as opposed to a standard propeller, plus increased efficiency in some areas of the submarine’s performance envelope. On the other hand, the pump-jet assembly is relatively heavy, and complicated, and may increase a submarine’s drag. However, the lead boat of the class and the protagonist of this story, HMS Swiftsure, was equipped with a standard unshrouded propeller.

In total, six Swiftsure class hulls were completed: HMS Swiftsure (S-126), HMS Sovereign (S-108), HMS Superb (S-109), HMS Sceptre (S-104), HMS Spartan (S-105), and HMS Splendid (S-106). Swiftsure was commissioned in 1973, and Sceptre, the last boat of the class in service, was decommissioned in 2010.

The hunted

Kiev was the lead ship of its class, known in the Soviet Union as Project 1143 Krechet (gyrfalcon), which received the NATO code Kiev class. This warship’s keel was laid on January 21, 1970, at the Black Sea Shipyard in Nikolayev on the southern tip of the Mykolaiv peninsula, in the Ukrainian SSR. The nearly completed ship was launched on December 26, 1972, for outfitting and was officially commissioned on December 28, 1975.

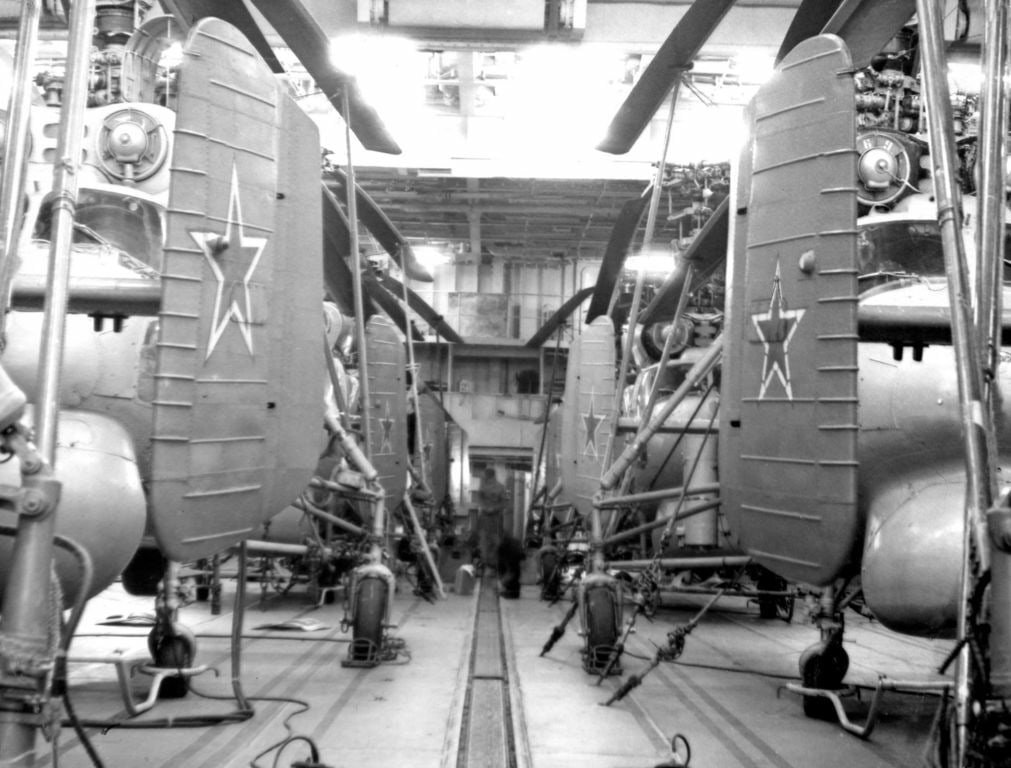

The design of the Kiev class was a surprise to many Western observers. A hybrid between a vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL)/helicopter carrier and a guided missile cruiser, the most recognizable features were the angled flight deck on the port side, a massive island on the starboard side, and a dedicated space on the bow with four huge twin launchers for the enormous P-500 Bazalt (SS-N-12 Sandbox) anti-ship missile; eight missile reloads were also provided. For anti-aircraft defense, there were two twin launchers for M-11 Shtorm (SA-N-3 Goblet) surface-to-air missiles and another two twin launchers for the point-defense Osa-M (SA-N-4 Gecko) missiles. For sub-surface threats, the Kiev carried two launchers for RPK-1 Vikhr (SUW-N-1/FRAS-1) anti-submarine missiles and two RBU-6000 Smerch-2 rocket launchers. With no catapult, Kiev operated only VTOL-capable Yak-38 Forger fighter jets and Ka-25 Hormone helicopters. Two elevators moved aircraft between the hangar and the flight deck.

From the vast number of electronic systems installed in Kiev, the sonar suite is the most relevant to our story. It comprised a hull-mounted MG-342 Orion (Horse Jaw) low-frequency (LF) sonar, MG-335 Platina (Bull Nose) medium-frequency (MF) sonar, and a towed MG-325 Vega (Mare Tail) variable-depth sonar (VDS).

Kiev’s sister ships were Minsk and Novorossiysk, while the Baku (later Admiral Gorshkov) was built to an improved design and constituted a separate subclass.

Operation details

During the Cold War, the Soviet Navy regularly honed its skills and its command-chain efficiency during large-scale naval exercises, often in cooperation with submarines and aircraft. The exercise SEVER-77 (North-1977) lasted from April 14-22, 1977. The lead and commanding ship for the exercise was Kiev, which was still considered to be a new vessel, having been commissioned just two years prior; the crew was still mastering all the complex systems aboard.

The carrier’s powerful inner and outer escort screens were made up of the Project 1134A Berkut-A (Kresta II) class guided missile cruisers Admiral Nakhimov, Marshal Timoshenko, and Admiral Isakov and the Project 61 (Kashin) class destroyer Smyshleny.

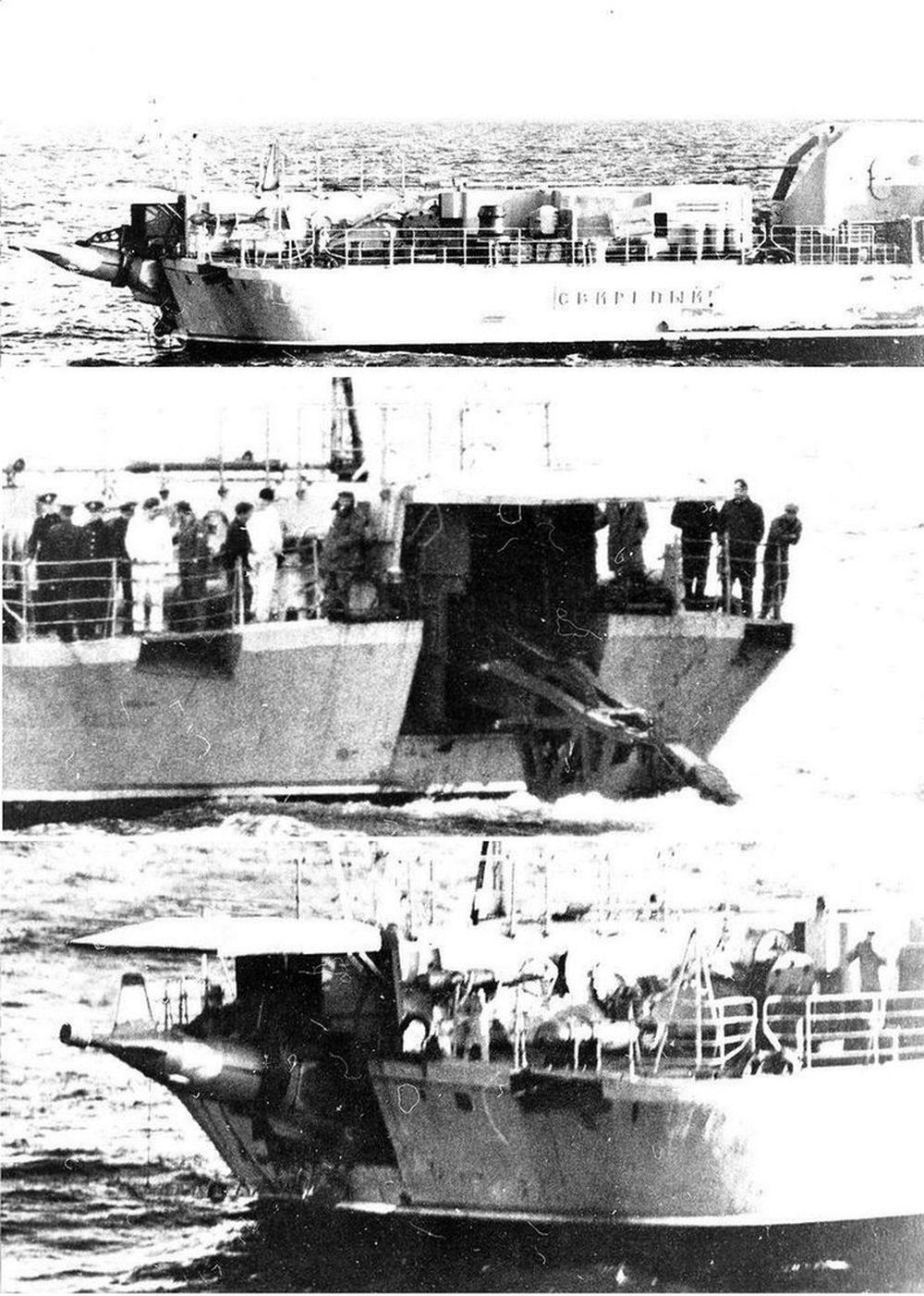

The major part of the exercise took part in the Northern Fleet’s ‘home waters’ of the Barents Sea and the fleet, accompanied by the Project 1559V Morskoy proctor (Boris Chilkin) class replenishment oiler Genrikh Gasanov, also made a trip to the Lofoten archipelago in the Norwegian Sea to practice replenishment-at-sea (RAS) procedures in very rough weather conditions off the Norwegian coast.

Shortly after discovering the Soviet surface ships active in the exercise, Swiftsure, commanded by Capt. John Speller, was ordered to record Kiev’s acoustic signature and to collect other intelligence. As each ship has its own specific sound signature that can be recognized by a trained sonar operator, the signature of Kiev was a very important piece of information that would allow the Royal Navy and its allies in the future to recognize the carrier much faster and more reliably.

The captain ordered Swiftsure to approach Kiev slowly and carefully from astern, hiding in its massive wake and taking full advantage of the blind spot of the carrier’s sonar systems. The blind spot — also called ‘baffles’ — is an area extending behind the ship where the bow-mounted sonar has no coverage. Submarines and surface vessels often use towed sonar arrays (TSA) and variable-depth sonar (VDS) to cover this blind spot and listen for enemy vessels approaching them from astern. Kiev was equipped with VDS but compared to a more complex TSA it was essentially just one towed sensor allowing the sonar operators to listen for suspicious sounds below the thermocline — the transition layer between the warmer mixed water at the surface and the cooler, deeper water below. A TSA contains a series of hydrophones extending, if needed, through multiple thermoclines, thus giving much better situational awareness.

Swiftsure’s captain took his time to carefully plan the approach, matching the sub’s speed to the carrier, all the while remaining undetected by Kiev and its powerful escorts. Getting this close to the enemy’s massive carrier required nerves of steel, coordination, and the concentration of every single man aboard the Swiftsure. The approach phase took several exhausting hours and had to be carried out without a mistake — the discovery of a Royal Navy submarine in such close proximity to a Soviet capital ship would most certainly trigger a major incident.

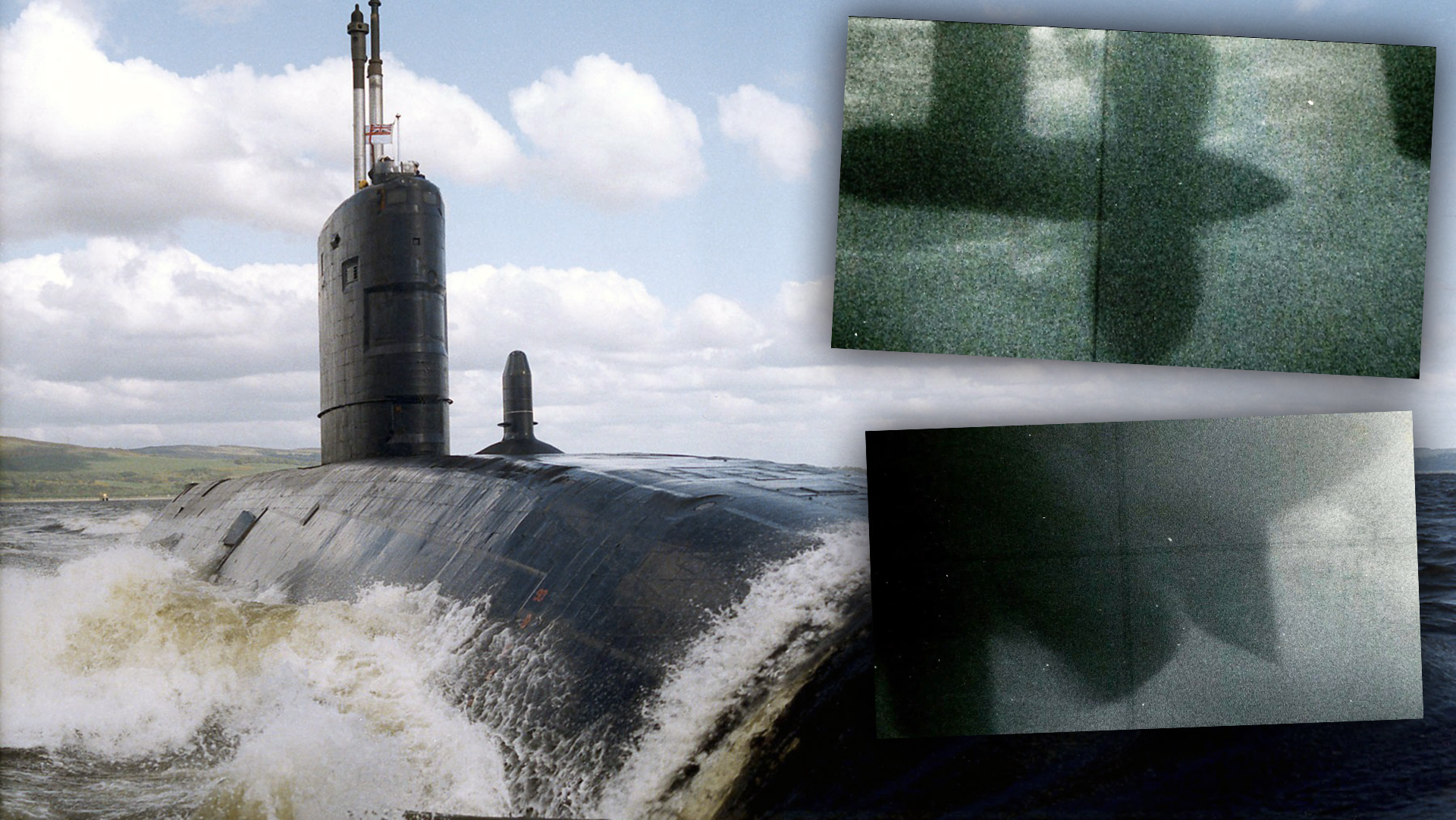

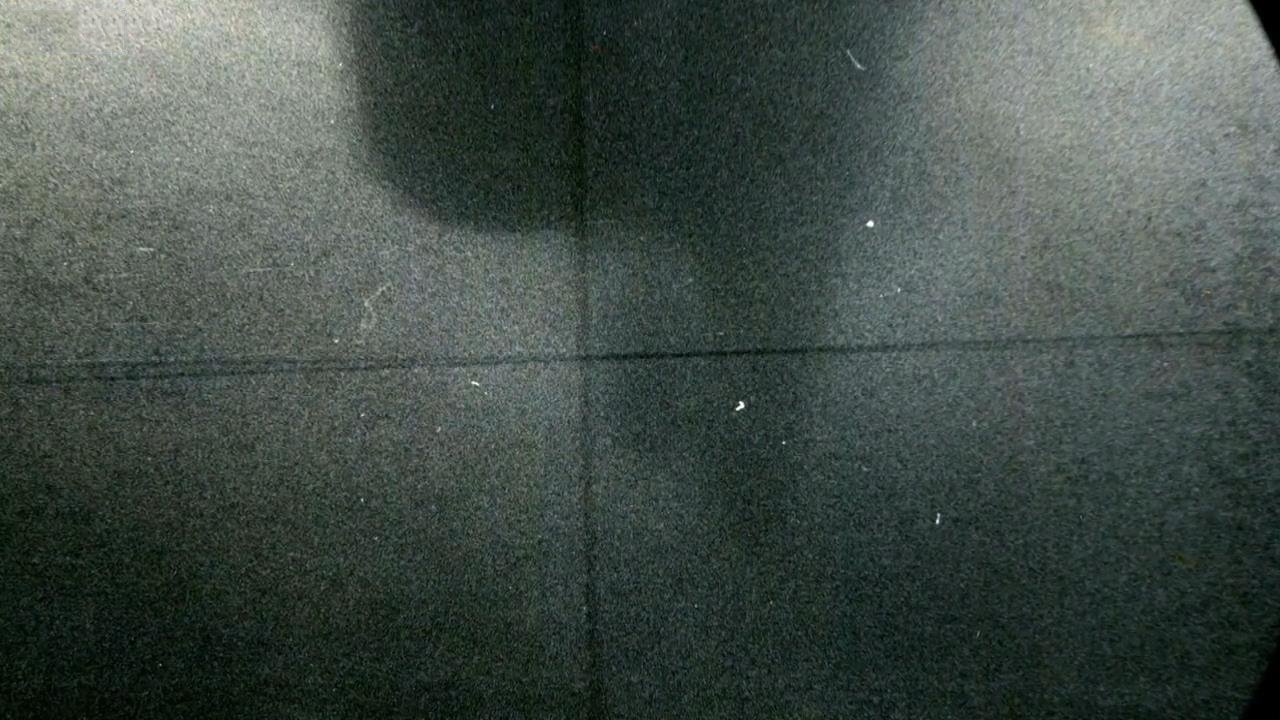

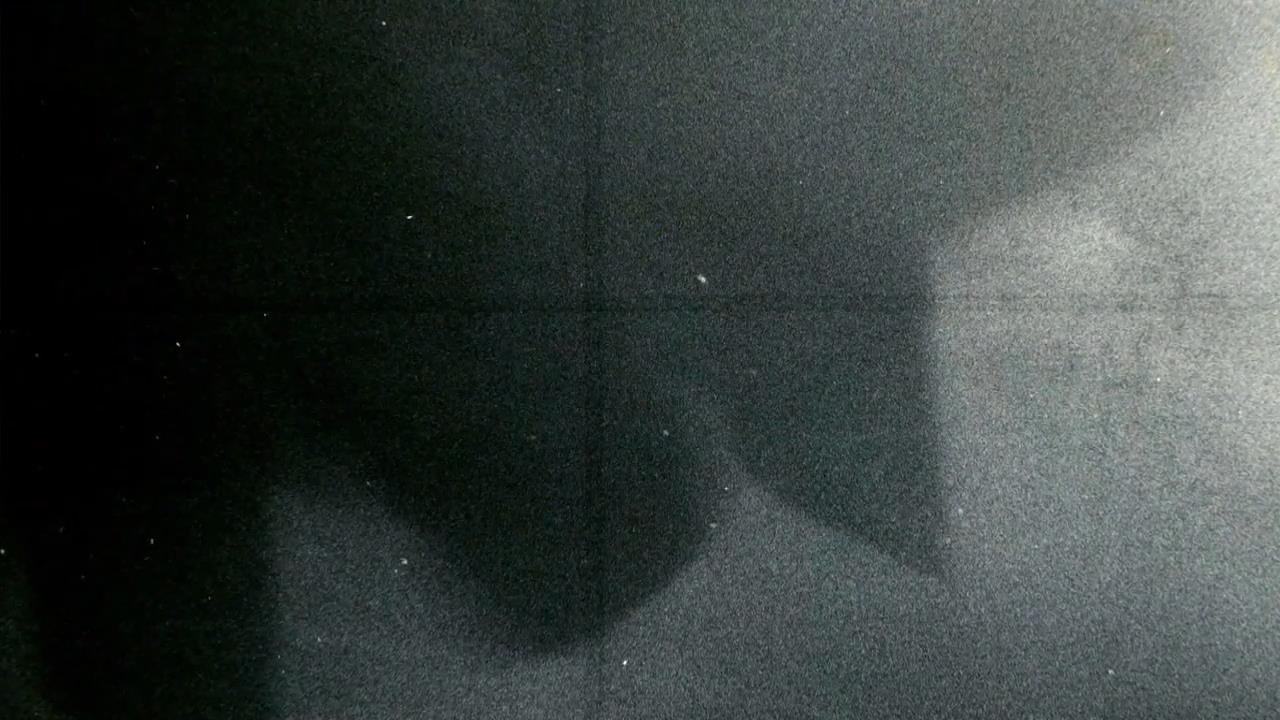

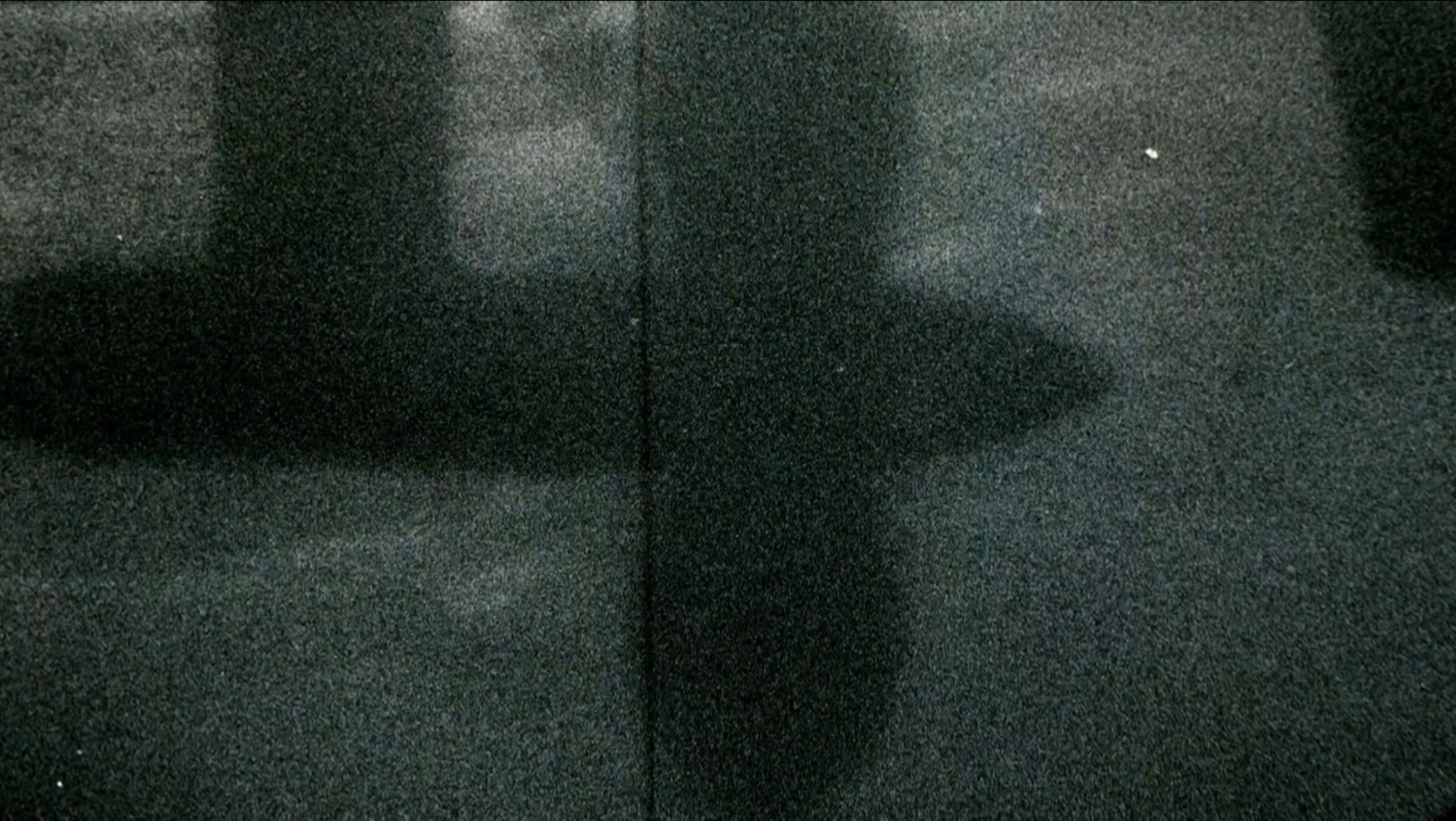

After spending hours lurking in the depths and carefully correcting its position relative to the carrier above, Swiftsure slowly began the ascent with its periscope raised to monitor the procedure. Finally, the crew was able to see the carrier’s massive propellers churning the water — the periscope was now just a few feet from the ocean surface and only 10-12 feet from Kiev’s hull.

Being this close to a moving capital ship displacing around 42,000 tons with a submarine displacing 4,500 tons was extremely dangerous. A sudden course change by the carrier might have caused a collision or exposed the nearly surfaced submarine to the patrolling ASW helicopters or aircraft. Swiftsure, however, remained undetected and began recording the acoustic data. Apart from this intel, the sub was also able to take close-up photographs of Kiev’s hull shape, rudder, and propellers — invaluable pieces of data enabling Royal Navy and Western experts to better analyze the performance of the carrier. After all the important recordings and photos were collected, Swiftsure began to slowly sink back into the depths, leaving the Northern Fleet’s capital ship and its feared escorts unaware that they had just been masterfully and covertly spied upon.

Swiftsure returned home on the 70th day of the deployment. The submarine’s captain, John Speller, later received a small model of Kiev’s propellers to commemorate this incredible mission and its results.

Differing legacies

Designed with a hull life of at least 25 years, HMS Swiftsure was prematurely decommissioned and de-fueled in 1992 when, during a refit, several dangerous cracks were found in the reactor piping. The rest of the Swiftsure class boats were decommissioned in the mid-to-late 2000s. Their more capable successor was the Trafalgar class, essentially a modified Swiftsure with several major upgrades, including the use of anechoic tiles and other advanced noise-reduction features.

Kiev went through an overhaul and modernization in the 1980s but was decommissioned in 1993, just two years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. On June 30, 1993, the carrier was sold to China to become a theme park in Tianjin. After nearly two decades, it was turned into a luxurious hotel.

The other Kiev class vessels had unusual histories in the post-Soviet period. Minsk was also sold to China to become a naval museum in Jiangsu, while Novorossiysk was broken up by a shipbreaker in Pohang, South Korea in 1997. Admiral Gorshkov was sold to the Indian Navy in 2004 and renamed INS Vikramaditya (R-33). In 2013, this now heavily modified vessel was officially recommissioned at Severodvinsk in Russia and began a 26-day journey to its new homeport at INS Kadamba. Here it was inducted into the Indian Navy, with which it continues to serve. In 2016 Vikramaditya received a dry-dock overhaul, expected to provide a service life of 30-40 years.

The story of Swiftsure and Kiev in SEVER-77 is just one out of many similar covert operations conducted by both Western and Soviet navies. Today, of course, naval powers around the world continue to covertly collect highly sensitive intelligence using their latest and most capable assets, but these events will likely remain classified for many more years to come.

About the author: Matus Smutny is a Senior Lead Engineer in the automotive industry and has a lifelong passion for post-war naval history and technology. He maintains a digital gallery containing more than 137,000 photos and can be found on Twitter as @Saturnax1 .

Contact the editor: thomas@thedrive.com