Thanks to a patent filed for an engine intake duct design, we may have gotten our first look at least the basic design concept behind Russia’s long-in-development Tupolev PAK DA bomber. Work on the long-range subsonic bomber, ultimately planned to succeed the Tupolev Tu-95MS Bear-H and Tu-160 Blackjack, has been ongoing since at least 2007, but, so far, there have been no confirmed official models or artworks indicating how it might actually look, although it has been widely reported as a flying wing design.

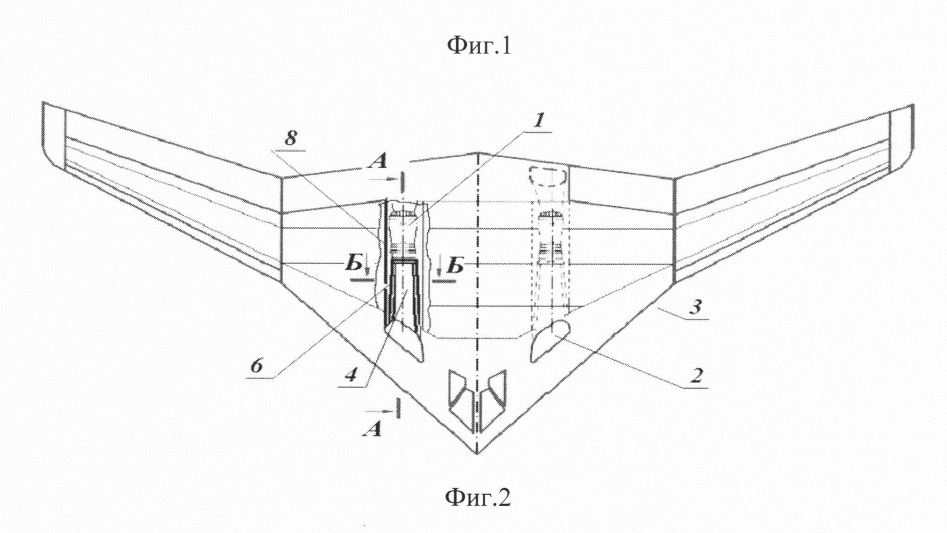

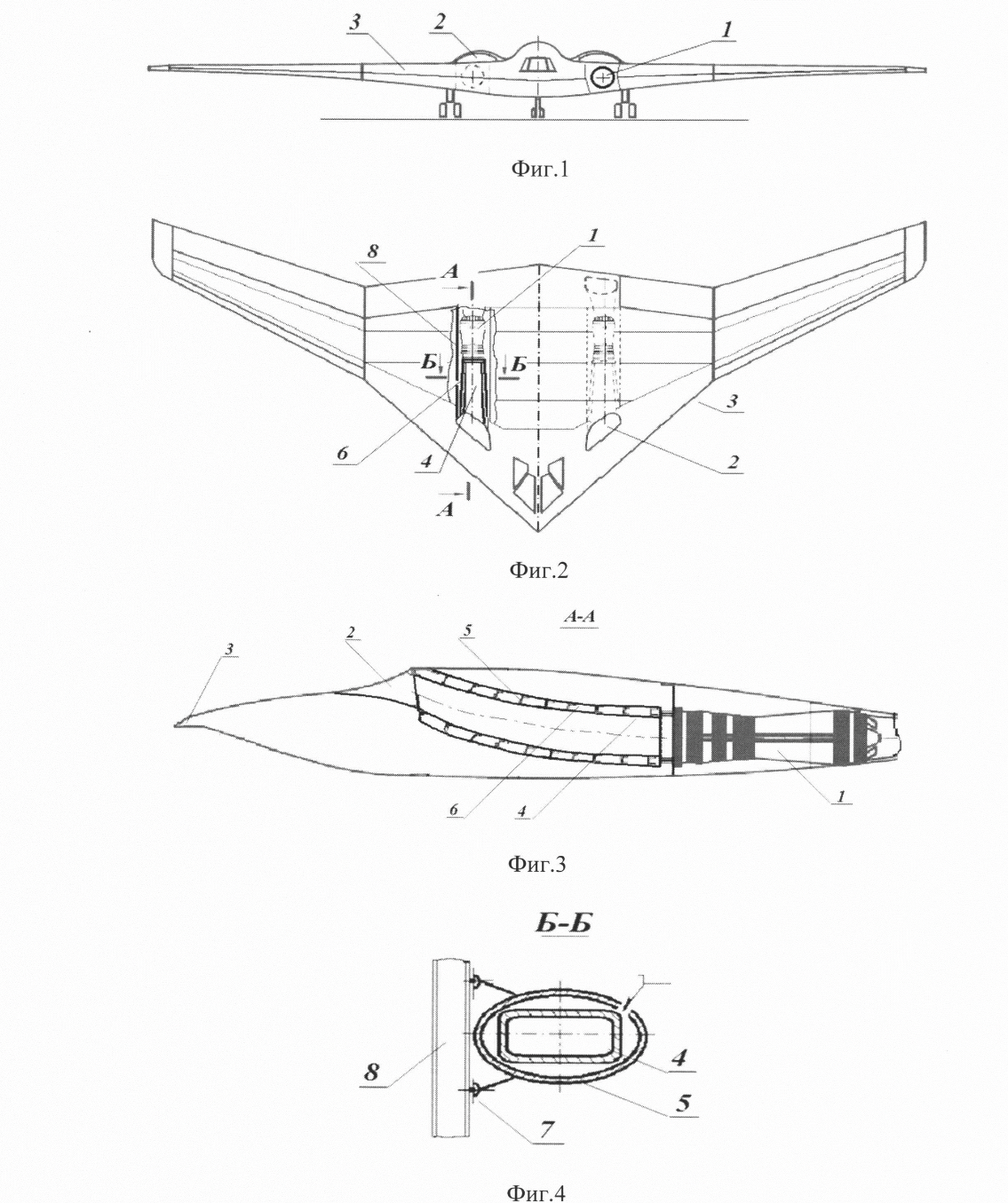

The drawings in question originate from a patent that was granted to Tupolev earlier this year and which concerns details of an aircraft engine intake. The intake is shown from the front, top, and side. But most interesting is the aircraft in which the intake is incorporated. While it’s worth noting that the plane design depicted is not described as the PAK DA, it’s certainly in keeping with semi-official and unofficial reports of the bomber’s general design. Nevertheless, there are some indications it may only be provisional or at least a work in progress.

The flying-wing design illustrated very loosely similar to the U.S. Air Force’s B-2 Spirit, with the same sharp ‘beak,’ forward-set cockpit, and with engine intakes on the upper surfaces of the wing/body, on either side.

Based on this drawing, however, there appear to be some major differences with the B-2, at least at this stage.

Where the Spirit is essentially a 35-degree angle flying wing/fuselage with a ‘serrated’ trailing edge, this apparent PAK DA design depicts an aircraft with a similarly angled nose but with a pronounced cranked wing. As a result, the narrower outboard sections of the wings have a much less severe angle of sweep. Compared to the B-2, the trailing edge is also far simpler, having more in common with cranked-kite layouts like the X-47B drone, and also with the Russian S-70 Okhotnik, although with reduced angles of sweep.

An official Russian Ministry of Defense video showing the S-70 Okhotnik drone:

Furthermore, the simplicity of the trailing edge, at least, is very loosely similar to official renderings of the U.S. Air Force’s new B-21 Raider. Again, however, it should be noted that the few depictions of the B-21 released so far may well differ in some aspects from the final aircraft.

Another difference is the powerplant arrangement, with two engines buried in the wing/body, unlike the Spirit, which has four turbofans. While the PAK DA was always expected to be a twin-engine design, based on the available artwork, the engine exhausts simply exit the trailing edge, with no sign of a more exotic platypus or shelf-type exhaust design. This would suggest, in this form at least, that the design is not anywhere as stealthy as the B-2, in both the IR and RF spectrums, especially when viewed directly from the rear hemisphere and especially from that direction and below. Overall, the intake and exhaust designs are some of the hardest to master in terms of low observability, something we have addressed in the past in relation to the B-21.

In general terms, the patent drawing suggests an aircraft that is clearly not in the very low observable (VLO) class but rather has some thought given to a degree of low observability (LO). Like the B-21, it could have a high operating ceiling, but in terms of stealth, it would seem to have the same kind of relationship to the B-2 as the Su-57 Felon does to the F-22 Raptor.

Most obviously, angle alignment is largely missing in this design, as is a LO exhaust concept. And of course, many other aspects go into an advanced stealth design, including elements that are not outrightly visible, like coatings, aperture design, and complex radar-defeating structures that lay beneath the skin. That being said, the final PAK FA may of course bring in more refined design elements, with more attention paid to LO, but it seems a design balanced between cost, technological know-how, performance, and low observability will be most likely, as we have seen in the recent past with advanced Russian designs.

Surprisingly, considering we haven’t previously seen official depictions of the PAK DA, quite a lot of information has already been released about the bomber’s supposed characteristics.

As long ago as 2014, Russian Air Force officials confirmed it would be a subsonic flying wing able to fly a distance of 15,000 kilometers — around 9,300 miles — without refueling.

Other, slightly less reliable sources have disclosed a planned takeoff weight of 145,000 kilograms (160 tons) and a weapons load of 30,000kg (33 tons). Weapons are expected to include new-generation standoff missiles carried on a pair of rotary launchers in internal weapons bays. The primary basic load is likely to comprise 12 new Kh-BD long-range subsonic cruise missiles, which are intended to have a greater range than the current Kh-101/102. The conventionally armed Kh-101 (known to NATO as the AS-23A Kodiak) has a reported maximum range of between around 1,870 and 2,480 miles and the nuclear Kh-102 is said to be able to fly further.

The PAK DA’s engines are expected to be derived from the NK-32-02 used in the Tu-160M. You can read more about that interim bomber here, and about the powerplant — the most powerful in production — here.

One prominent feature of the patent drawing that might not be found in the definitive PAK DA is the kinked wing. Russian aviation expert Piotr Butowski, in a recent article for Aviation Week, claims that the final aircraft will likely have a constant leading-edge angle, like that of the B-2 — and likely also the B-21 Raider. Indeed, that change would lead to a configuration much more similar to the official renderings of the B-21.

Whatever the relationship between the aircraft design in the patent and the finalized PAK DA configuration, this appears to be the latest turn in the saga of the enigmatic aircraft, designed to replace Russia’s current manned bomber fleet. To date, this program has been dogged by delays and limited funding.

With the Russian military now bogged down in the conflict in Ukraine and with sanctions affecting the production capacity of the country’s industry, especially with regard to high-technology aerospace components, the timing of the patent may be slightly surprising.

The PAK DA, or Perspektivnyi Aviatsionnyi Kompleks Dalney Aviatsii, which translates as Future Air Complex of Long-Range Aviation, dates back to at least 2007, when a competitive process was first announced. This saw Tupolev selected and awarded a three-year contract for conceptual design work in 2009.

In early 2013 the Russian Ministry of Defense approved Tupolev’s PAK DA proposal and a contract was awarded to Tupolev at the end of the same year for preliminary technical design work.

By 2014, Russian Air Force officials were confidently predicting the first flight of a prototype PAK DA in 2019, and initial service entry in 2023, but since then the program has moved in fits and starts.

Indeed, the Kremlin’s previous military campaign in Ukraine, including the annexation of Crimea and the earlier conflict in the Donbas region, saw the PAK DA program assigned a reduced priority. It was at this point, in 2014, that the decision was made to resume series production of the Tu-160 and postpone the PAK DA, as a cost-saving measure.

However, by late 2017, work had resumed on the PAK DA, with Tupolev receiving another ministry of defense contract, covering research and development, including completing and evaluating an undisclosed number of test aircraft. At this point, the aircraft was expected to be accepted for service in 2027.

Back in May, there was another update on the supposed timeline of the program, as reported by Butowski. He revealed that, for a few weeks only, a table of production plans was posted online by the Ilyushin company. This firm is responsible in turn for Beriev, which is one of the companies that will build components for the PAK DA.

The table, which considers the effect of the conflict in Ukraine, indicates that Beriev is to build six sets of parts for PAK DA aircraft by 2030, with the first two such sets in 2023. Another two sets should follow in 2024, and then one each in 2025 and 2026. The first three aircraft reportedly are test airframes, which suggests the next three could be pre-production examples.

Regardless, if that schedule holds, and that is highly questionable, bearing in mind the status of the Russian aerospace industry, then a PAK DA prototype could take to the air in 2024.

Dmitry Stefanovich, a Research Fellow at the Center for International Security, IMEMO RAS, has observed that the PAK DA could even be rolled out later this year, but adds that “there are serious doubts.” He also says that the first flight could happen around 2025 or 2026, followed by series production starting from around 2028 or 2029. In any case, the timeline will almost certainly lag behind both the delayed B-21 and China’s new H-20 bomber.

Perhaps most interesting, however, is the fact that the PAK DA apparently remains a central element of the Russian military’s plans, despite the war in Ukraine and the additional pressures it’s putting on manufacturing efforts. After all, as well as shortages of critical components caused by sanctions, there’s the requirement to provide attrition replacements and also to continue to replace older, Soviet-era equipment.

The big question, however, is whether there’s a realistic chance of Russia actually building the PAK DA, and getting it into the air, whenever that might happen.

In its favor is the fact that Tupolev appears to be taking a fairly low-risk approach to the project. While the large flying wing configuration is new for Russia, there are plans to use a significant portion of the subsystems and weapons from the Tu-160M and from other existing aircraft. At the same time, the S-70 Okhotnik will likely provide useful data in terms of flight control systems and LO in a flying wing design.

As well as the aforementioned engines, based on those of the Tu-160M, the PAK DA should have an active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar derived from that used in the Su-57 Felon fighter jet.

On top of that, it seems the program overall is by now relatively advanced despite the earlier delays. There is also the question of prestige, and the high priority afforded the Long-Range Aviation branch, as a part of the strategic nuclear forces.

On the other hand, the Su-57 program has shown that while Russia may well be capable of building new-generation combat aircraft, with full suites of subsystems, including avionics and weapons, actually manufacturing these in meaningful numbers is a different matter. The Kremlin placed an order for 76 examples of the Su-57 in 2019, but so far only a handful of pre-production and production aircraft have been delivered to test units.

It’s not hard to imagine that a PAK DA prototype might take to the air, only to be followed by only a handful of pre-production aircraft. That will likely also depend to a significant degree on progress with the Tu-160M. If the new-build Blackjack ends up being considerably cheaper than the PAK DA, there would be a strong argument for pursuing it solely instead, and perhaps incorporating some advanced subsystems from the PAK DA as production continues. The question of cost is likely one that will loom over the PAK DA program, especially as other big-ticket defense programs have already taken hits, even before the war in Ukraine.

On that, it’s hard to envisage Russia having the funds to replace its bomber fleet with an advanced flying wing type or that it would prioritize doing so while its economy is being crushed by sanctions and its military has taken huge losses in equipment and manpower in a war that has no foreseeable end at this time.

There is also an argument that Russia doesn’t really need a stealthy cruise missile carrier. After all, as demonstrated in the Syrian and Ukrainian campaigns, their aircraft launch their missiles from standoff distances anyway. Nevertheless, it could be the case that anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) and long-range defensive capabilities are making the concept of a penetrating cruise missile carrier more relevant.

Official Russian Ministry of Defense video showing Tu-160s launching cruise missiles during the Syrian campaign:

Most critically, however, is the issue of sanctions, especially as regards access to high-technology electrical components. Without these, building any kind of sophisticated aircraft, not least a long-range bomber, will be difficult. As Butowski states, “If the Western embargo on deliveries, introduced after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February, is effective, it could block aircraft production in Russia.”

Unless a viable workaround is found for this problem, and considering all the other issues at play, the PAK DA could well become yet another loser as a result of Russia’s ongoing offensive in Ukraine.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com