When asked what it was like to fly the Antonov An-225 — then the world’s biggest airplane — with a 60-ton space shuttle strapped to its back, Oleksandr Halunenko is rather nonplussed.

“It’s a heavy vehicle, so it’s quite slow whenever you make a turn or whenever you make any movement,” he says from the home he built two decades ago in war-torn Bucha, Ukraine. “And this is called inertness.”

Sensing disappointment with the response, his wife, Olha Halunenko, a deputy professor of psychology who specializes in pilot psychology, interjects.

“I want to comment as a psychologist,” she says in one of several conversations the couple had with The War Zone over social messaging apps with the help of a translator. “Oleksandr has a very specific feeling towards perceiving difficulties and stress.”

To explain her husband’s seeming nonchalance, she offers an example of what his emotions were like during the brutal Russian occupation of their hometown.

“One night, we were sleeping on the second floor of our house when the bombs started falling,” she says. “There was shelling in our neighborhood and the neighboring houses were on fire and I’m telling him, ‘Let’s go to the basement, let’s get to shelter.’”

The response from Oleksandr — who years earlier earned one of his nation’s first Hero of Ukraine medals for saving another aircraft from a deadly disaster — was eerily calm.

‘“No,’” she says he told her as Russian explosions rocked the neighborhood. “‘First we have to make up our bed.’”

Danger, she says, “is different for Oleksandr than any other person.”

But when it comes to the plane itself, it’s a very different story.

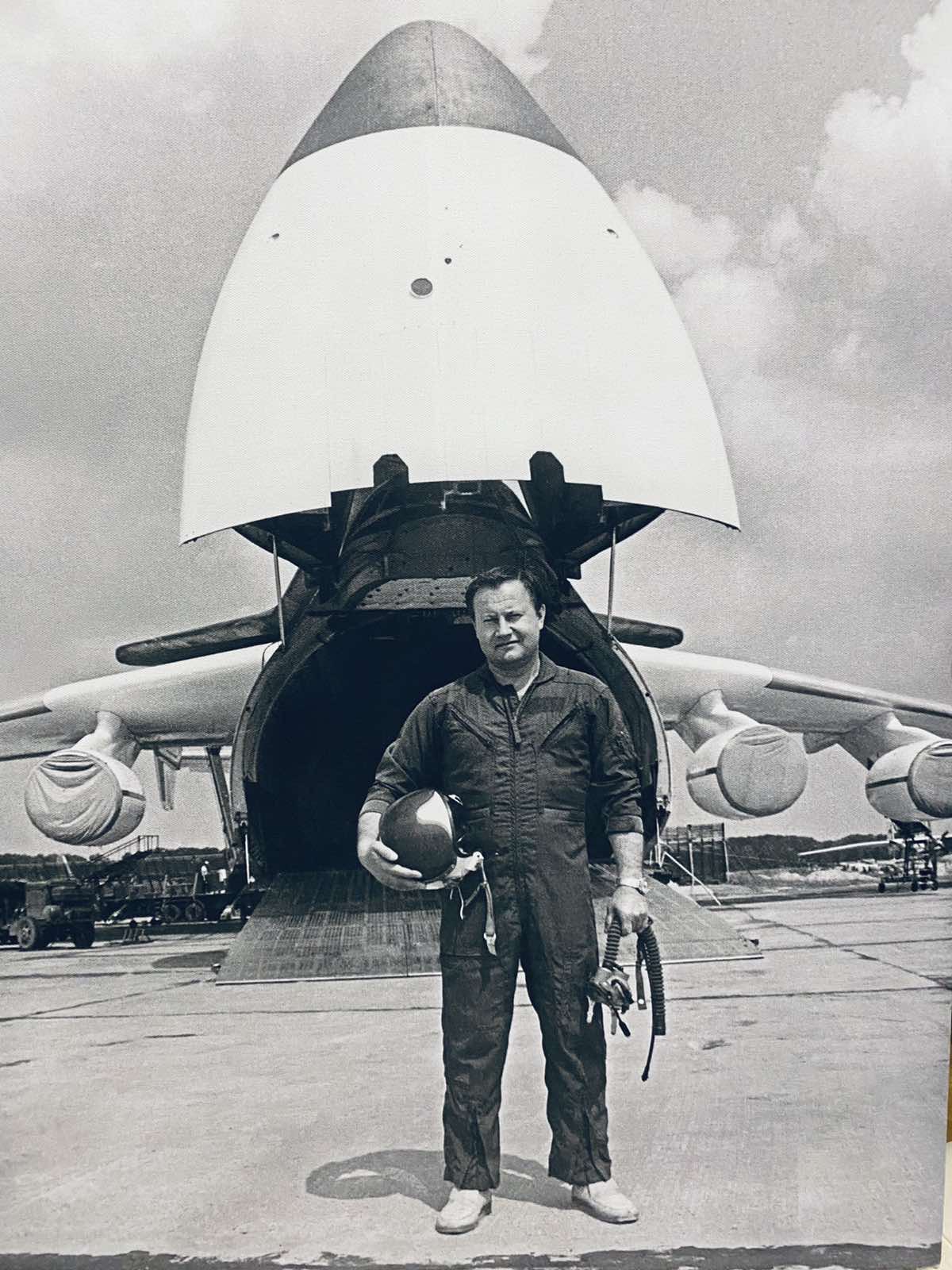

He was part of the team that designed the jet known as Mriya — Ukrainian for “dream.” He was the big jet’s first pilot. He was the only one to fly it with the Soviet Union’s space shuttle, named Buran, on its back. And was in the left seat for a plethora of its world records.

His love for the airplane is palpable in his home, which is a defacto Mriya museum, filled with photos and models and paintings, even one he and his wife made during the occupation.

His first visit to nearby Hostomel Airport after Bucha was liberated stirred up some deep emotions.

That’s when he saw the burned-out wreckage of Mriya. It was destroyed sometime after the Russians began their all-out war on Ukraine on February 24.

“It felt like your child had been killed,” Oleksandr Halunenko says. “Talented, beautiful, whom you loved very much and whom everyone who saw him admired. It was a part of my soul.”

Meeting Mriya

Oleksandr Halunenko’s journey to Mriya, a flying marvel with six turbofan engines, a wingspan nearly as long as a football field, and an iconic split tail, began when the 76-year-old was in the 11th grade and joined an aviation club.

Encouraged to learn how to be a pilot, he flew an old Soviet Yakolev Yak-18 propeller training plane. He enjoyed it so much, he decided to continue his education at a Soviet military aviation academy and became a pilot in the Soviet Air Force. In 1975, he was sent to work as a test pilot with the Antonov aircraft factory in Kyiv.

As he explains his background, Olha interjects once again, taking her phone to the window and pointing it at a nearby house that was burning during the occupation.

“From our window, we could see how the helicopters would come in and how they were shelling and bombing and how things caught on fire,” she says. “I just decided to take the chance to show you now, while it is still light out.”

With that, she hands the phone back to her husband, who explains that he tested several aircraft, moving up from turboprop transports like the Antonov An-28, the Antonov An-32, and the Antonov An-70 to jets like the Antonov An-72 and Antonov An-74.

He was part of the testing program for the 227-foot-long, four-engine Antonov An-124 Ruslan, which at the time was the world’s largest cargo plane. Designed as a heavy strategic military transport able to carry up to 150 tons of cargo, it made its maiden flight from the factory aerodrome near Kyiv on December 24, 1982, with Halunenko as its co-pilot.

But while the Ruslan was big, the Soviet Union decided it needed an even bigger aircraft, says Halunenko, to help it compete with the nascent U.S. space shuttle program.

The USSR decided to create its own shuttle, Energia Buran. But everything it needed to produce it was in the European part of the Soviet Union, while the space testing facility was located in Baikonur, Kazakhstan, nearly 2,000 miles to the east.

“They needed some transport aircraft that would be able to transport all of the needed huge parts from one part of the USSR to another,” says Halunenko. “That is when they made the decision to create a big transport aircraft based on Ruslan, just bigger.”

The Antonov design team created Mriya by expanding Ruslan. They lengthened the fuselage and wingspan, added two engines, created fuselage barrel extensions fore and aft of the wings, redesigned the tail with twin vertical fins, increased the number of landing gear tires to 32, and removed the rear cargo doors.

Mriya’s six Ivchenko Progress/Lotarev D-18T, three-shaft turbofan engines each produced a maximum thrust of nearly 52,000 pounds-force.

Its twin tail enabled the aircraft to carry large, heavy external loads — like Buran — which would normally disturb the airflow around a conventional central vertical tail.

Unlike the Ruslan, Antonov only produced one finished An-225 and one additional fuselage.

Having participated in Mriya’s design phase, Halunenko says “there were no surprises” when he took it for its first flight, on December 21, 1988, from the factory aerodrome near Kyiv.

“Whatever the constructors have written, designed, and whatever they knew about this is exactly what happened,” he said.

Just three months after piloting Mriya’s maiden voyage, Halunenko made history again.

“We decided that we should try to see if this aircraft could set some records,” he says.

That mission was accomplished on March 22, 1989. As Halunenko once again served as pilot, Mriya took off with 156.3 tons of cargo and established 110 world speed, altitude, and weight-to-altitude records within 3 hours and 45 minutes of flight.

A few months later, on May 13, 1989, Mriya took off from Baikonur for the first of 13 test flights with Buran on top and Halunenko in the pilot’s seat.

As he talks, he illustrates what it was like to fly with the shuttle on the back by displaying a model of the assembly.

“This is how it looked like when I was testing it,” he says. “We were testing it in Kazakhstan for stability and sustainability of flight as well.”

It was during this period that Halunenko says he experienced his favorite moments flying Mriya.

The first time flying to the Paris Air Show, in June 1989 was the best of all, he says.

The huge, record-breaking aircraft had traveled from Kyiv with Buran on its back to highlight the Soviet Union’s aviation prowess.

Presented with a unique opportunity to showcase this flying behemoth, dispatchers at Paris-Le Bourget Airport wanted to give Parisians a special show.

“They decided to break all the possible rules and asked us to make a circle around Paris,” says Halunenko.

It was a beautiful sunny day and the dispatchers wanted “all the people on the ground to see and admire this big aircraft with the shuttle on top.”

Such adulation, says Halunenko, was common wherever Mriya went.

And that led to his second favorite Mriya memory, this time at an airshow in Oklahoma a year later.

Media reports about the pending visit of the world’s biggest airplane created a stir, says Halunenko. People from all over wanted to get a look at Mriya, lining up in a queue more than a kilometer long.

The nose of the huge aircraft lifted up and people began filing in.

Curious visitors began asking questions.

“‘Oh is it Boeing?’” Halunenko recalls some of the queries.

“‘No it’s not Boeing,’” he responded, ‘it’s Antonov.’”

“‘Really, Antonov?’” he says he was asked. “Like they never heard of it.”

“‘Where is it made?,’” others asked.

“‘It’s made in Kyiv,’” said Halunenko.

“‘Which state is it?,’” he chuckles, explaining he had to respond that Kyiv is in Ukraine.

“‘So which state is Ukraine in?’”

After receiving more of the same questions, Halunenko grabbed a map and taped it to the wall of the cargo compartment. He circled Ukraine so that the next group of visitors didn’t have to ask so many questions.

“Finally, I was interviewed by the local media and I made a little joke with them,” says Halunenko. “In addition to showing you the biggest aircraft in the world, we also taught your people geography.”

New mission for Mriya

Part of the original plan for Mriya, says Halunenko, was that a spaceplane would eventually be able to take off from Mriya in midair.

But alas, that was never to be.

“Oleksandr came to be the first and only pilot to fly with Buran connected to it,” says Olha Halunenko. “No one else was doing that. He started flying like this and then the Soviet Union collapsed and no one else was using the aircraft for this purpose anymore.”

The collapse, in December 1991, ended the Soviet space program and any dreams of launching a shuttle off Mriya. But Antonov still had the An-225 and ultimately, it was decided that the world’s biggest airplane would become the world’s biggest commercial cargo hauler.

That would lead to another first for Halunenko, albeit many years later. And ultimately, another brush with history.

But before that would happen, Halunenko was piloting an Antonov An-70 in April 1997, for the first flight of the aircraft’s second prototype when things started to go wrong in a hurry.

“Four times the electronic system control refused” to work properly, says Halunenko. Each time, he says, he tried to make it work. So he opted to deviate from guidelines, land the aircraft and save the lives of the crew, its passengers, and Antonov’s reputation. For that, he earned one of his nation’s first Hero of Ukraine awards.

The incident didn’t keep Halunenko from flying and on May 7, 2001, he was the pilot when Mriya made its first flight after reconditioning following seven years of downtime in Kyiv.

During that time, investors spent more than $20 million to fully restore Mriya for its return to the skies.

Among other improvements, Motor-Sich, a Ukrainian aviation engine manufacturer, paid for six new D-18T turbofans. In addition, the aircraft was made quieter and its cargo hold floor was strengthened. A month later, Ukrainian civil aviation authorities issued its type certificate.

They set Mriya’s maximum takeoff mass at 629.9 tons and limited its airframe life to 8,000 flight hours, 4,000 cycles, or 25 years.

It would never make it long enough to fulfill any of those figures.

But there was more glory to come before she was destroyed.

Three months after Mriya was newly certified, she set 124 more world and 214 national speed, altitude, and weight-to-altitude records. Once again, Halunenko was the pilot.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense had Mriya ship five tanks, weighing a combined 253 metric tons, says Halunenko.

When he landed, he found out the world had substantially changed.

“I came home and turned on the TV and saw the news about the terrorist attack that happened.”

It was September 11, 2001.

In typical Halunenko fashion, the pilot shrugged off the accomplishment, leading his wife once more to explain why.

“He’s an extremely emotionally stable person,” says Olha Halunenko. “Everyone is expecting from him some emotions and certain wow, but he’s not showing that because of his emotional stability.”

This time, she pointed to his reaction during the 1997 An-70 mishap as another reason why her husband hasn’t gotten excited about the world records.

“Everything that could go wrong basically went wrong,” she says. “He managed to save the aircraft and the people on board and also the reputation of the company.”

When he finally left the aircraft and was interviewed, “his words were pretty calm, saying ‘it was a very hard flight.’

“Whenever he’s reporting on something or talking about it, it sounds as if this is a normal working conversation,” says Ohla Halunenko. “Nothing more than that.”

War comes to Bucha

Oleksandr Halunenko stopped flying in 2004, when he was 58, says his wife. He began to receive a pension but still works as an advisor to the president of Antonov.

But, she says, he can’t remember the last time he piloted Mriya.

In 2006, he won a seat in Ukraine’s parliament, serving one term.

Being a pilot, his wife explains, was easier than being a politician.

“When you’re in the aircraft you can always forecast what the aircraft is going to do, how the aircraft is going to respond to certain situations,” says Olha Halunenko. “Whereas you cannot predict what will happen in the parliament. Politics is a completely unpredictable thing.”

Politicians, she says, “may act against human logic, whereas in the aircraft, this is just simply not possible.”

Serving as a part-time advisor to the president of Antonov, where once in a while he is invited to give lectures, motivational speeches, and sometimes participate in the educational process, Oleksandr Halunenko was hoping to live a quiet life with his wife in their home in lovely, tree-filled Bucha.

But by January 2022, the Halunenkos, like much of the rest of Ukraine, knew that such quiet was at best ephemeral.

“We did know that [the war] was gonna happen,” says Halunenko, “especially with what the Americans were saying, contrary to our government, that was saying ‘no, don’t worry, everything is fine.’”

Despite all the warnings, Halunenko says he had no intention of fleeing.

“I cannot leave my house,” he says. “This is my home and I don’t want to run away.”

Besides, he did not expect his town to become the focus of the eventual Russian assault.

“We never thought that we could happen to be in the epicenter of the events,” he says. “We called all our friends, saying, ‘please come to Bucha. It’s safe here. We have a big basement and enough space for all.’”

The thinking, says Halunenko, was that “Kyiv would be a more scary place to be.’”

As it turned out, it was a good thing none of those he called showed up.

Early on the morning of February 24, Bucha was rocked by war as Russian paratroopers sought to secure Hostomel Airport, with its long runway that could serve as a staging ground for an assault on Kyiv.

The airport was close to their house, about a seven-minute car ride away, says Halunenko, who measured the distance in time, not kilometers.

From their third-floor window, they could see helicopters flying and paratroopers floating down from the sky.

“We did hear the explosions,” says Olha Halunenko. “We did hear some shooting, then we saw big columns of smoke.”

By 5 a.m, “everybody started calling,” says Halunenko.

His granddaughter was the first to call, to say Ukraine was being invaded by Russia.

“We still had our mobile connection and internet, TV, and radio,” he says. “So we were aware of what’s going on.”

For a few days, the Halunenkos hosted nearly a dozen people, who slept on mats in the basement. But they quickly left.

As the fighting wore on, Oleksandr Halunenko says he could tell from all the fighting at Hostomel that his beloved Mriya was damaged.

It had to be.

How badly, however, he had no way of knowing, because the couple sequestered themselves in their house for more than a month. There was no electricity. No way to communicate with the world beyond their sturdy walls.

The couple went into survival mode.

They had some food in their own freezer and some from a next-door neighbor who fled. There was wood for the fireplace. And just enough gasoline to power up a generator for an hour or so a day to keep the perishables cold and phones charged, even though service was spotty.

They learned to sort the trash because garbage trucks were no longer operating. Ever the tinkerer, Oleksandr Halunenko built a small platform in the fireplace so they could use it as a cookstove.

Complicating matters were the couple’s two dogs, Barin, an eight-year-old German shepherd, and Bassarey, an 11-year-old husky.

“So it’s not only we have to calm down each other,” says Olha Halunenko. “We had to soothe those two dogs because they also were worried.”

The only time the Halunenkos left their home was when Russians searched their neighbor’s home and broke down the door and smashed their gate.

Oleksandr Halunenko went out to close the gates and make sure no one was stealing their stuff.

There was constant gunfire and bombs going off.

Olha Halunenko urged her husband to come inside.

“I was like, ‘let’s just close this door as quickly as possible and go into our basement,’’ she says.

Halunenko was having none of it.

“Imagine all this shelling and Oleksandr is standing there, measuring precisely the door and some board to fit in there,” says Olha Halunenko. “He’s very resistant as a person in a stressful situation. He doesn’t lose the reason. He just does precisely what he has to do.”

At that moment, Halunenko was intent on fixing the door and fence.

When he finished fixing the door, he saw some neighbors and asked them to help.

“They said, ‘you’re crazy, there’s shelling and bombs everywhere,’” Olha Halunenko says.

Her husband repeated his plea.

“And they said, ‘OK, the Hero of Ukraine is doing this, we will go and help.’”

On the morning of March 20, the Russians showed up at the Halunenko house.

“They were searching if we have anything suspicious or any guns,” says Olha Halunenko.

The first thing they noticed was pictures of Mriya everywhere. And a gallery of photographs with her husband taken over the years with the first four presidents of Ukraine.

“They stopped here in the corridor and then started questioning ‘why so many airplanes on the walls? Are you a pilot?’” says Halunenko.

“‘Yes,’” he responded. “‘I was a pilot. I was a pilot who was flying this aircraft.’”

So while the Russians crashed into their home in a very aggressive manner, “as soon as they knew that there was a pilot, they calmed down,” says Olha Halunenko. “They said, ‘sorry for interfering in your home.’ They just searched the house and made sure we didn’t have any arms and they just left.”

To help pass the time, Oleksandr and Olha decided to work together on a painting of their own.

It started out as a beach scene, with palm trees and the ocean. It was a scene, says Olha Halunenko, meant to distract them from the stark reality of living under Russian occupation.

But then they realized that Mriya was damaged, so Oleksandr painted her in as a cloud in the sky.

It would not be for another two weeks that the first Ukrainian volunteers returned to Bucha on April 4, finally able to make it across bridges that had been destroyed and roads that had been mined.

That’s when the couple felt some sense of relief. And gained the beginning of an inkling of just what had happened in Bucha, now the ongoing focus of allegations that the Russians committed horrific war crimes, randomly killing innocent civilians and leaving their bodies out to rot.

They knew of one neighbor who was killed by the Russians, gunned down by a drunk soldier who broke into their home.

But even at this point, they could not leave their home and see what the Russians had wrought.

“The Ministry of Emergency sent texts to all the people who are still in Bucha that we should stay in our houses and it’s not allowed to leave because the area is mined,” says Ohla Halunenko.

The Ukrainian military came out to clear the mines, but the ensuing explosions made the couple nervous.

“We heard the explosions here and there once in a while,” says Ohla Halunenko. “So it’s not fun to leave your house.”

On April 16, things changed.

A New York Times reporter, accompanied by the Ukrainian military, stopped by the house.

“‘Do you want to go see Bucha?’” Halunenko recalls a journalist asking him.

“And I was telling them, ‘what about the checkpoints?’”

The answer, says Halunenko, is that everything was organized, the journalists had press credentials and so they were able to make their way to Hostomel.

That’s where he saw Mriya for the first time since the invasion.

Parked under a partially destroyed massive aircraft shelter, she was a wreck, with much of her cockpit and forward fuselage in pieces and several engines charred.

Ukrainian authorities, says Halunenko, are conducting an investigation into why Mriya was not moved before February 24, when Russians assaulted the airport on the first night of the war.

Halunenko says Mriya was at Hostomel undergoing routine maintenance.

“Some people there on the top, they must have known something” about the impending danger, yet Mriya remained at Hostomel, says Halunenko.

“So it’s on them,” he says.

“It is not clear how Mriya was destroyed,” the New York Times reported. “Ukrainian soldiers said that they intentionally shelled the runway to prevent the Russians from using it. The Ukrainians said it was not their shells that hit Mriya, whose hangar is about 700 meters from the runway.”

Nobody knew exactly who hit the plane, the paper reported.

But one thing was certain, Halunenko tells The War Zone.

“I’m not a constructor,” he says. “I can only judge as a pilot. But from what I saw, Mriya cannot be restored.”

There were some parts, he says, that appeared undamaged and could be reused. Two or three of the engines, for example, can still be restored. Some parts of the tails too, as well as some systems on the wings.

“But they are just little parts,” he says. “This Mriya cannot be restored, but some systems can be, or used for the next airplane.”

The new Mriya, if there is one, “will have to be built from scratch,” says Halunenko. “It will have all new systems. It will be of a similar class, but it won’t be the same, of course.”

It’s possible, says Halunenko, that a second An-225 fuselage built by Antonov, could be used as the foundation for Mriya II.

Though he does not know what it would cost, such an endeavor is a great challenge, Halunenko acknowledges.

“Unfortunately, it needs a lot of investment,” he says, adding that Ukraine does not have the funds for such a project. “It can only be built with donations.”

Ukroboronprom, the Ukrainian defense industry conglomerate of which Antonov is part, says that building a new Mriya will cost more than $3 billion and take five years.

The funds, it says, will come from Russia via war reparations.

“Ukraine will make every effort to ensure that the aggressor state pays for these works,” Ukroboronprom states optimistically on its website. “The occupiers destroyed the airplane, but they won’t be able to destroy our common dream.”

The aircraft known as “Mriya will definitely be reborn. Our task is to ensure that these costs are covered by the Russian Federation, which has caused intentional damage to Ukraine’s aviation and the air cargo sector.”

To help fulfill this dream, Antonov has launched a crowdsourced fundraising campaign aimed at building a new An-225.

“Please be advised that in order to ensure full transparency, report on arrival and use of funds for the restoration of the world’s largest An-225 “Dream”, DP “ANTONOV” has opened a separate target multi-currency account for the deposit of money,” the company notes on its Facebook page.

This campaign may be as unrealistic as expecting Russia to pay for rebuilding Mriya.

As of May 2, the effort had raised a little more than $4,200.

Halunenko, never one given to gush or bluster, is more realistic.

He would love to see Mriya fly again, but he knows it won’t happen without an international effort.

“We have to engage in cooperation with the US, Canada, and European companies,” he says. “Ultimately, it will be a new aircraft that will require basically all the systems to be updated and modernized. In the world of developing systems, things that were installed on the aircraft one year ago are no longer modern today.”

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com