There have been rumblings regarding some sort of nuclear incident—or possibly incidents—in the Arctic over the last month. Multiple reports, some of them from official monitoring organizations, have reported iodine 131—a radioactive isotope often associated with nuclear fission—has been detected via air sampling stations throughout the region.

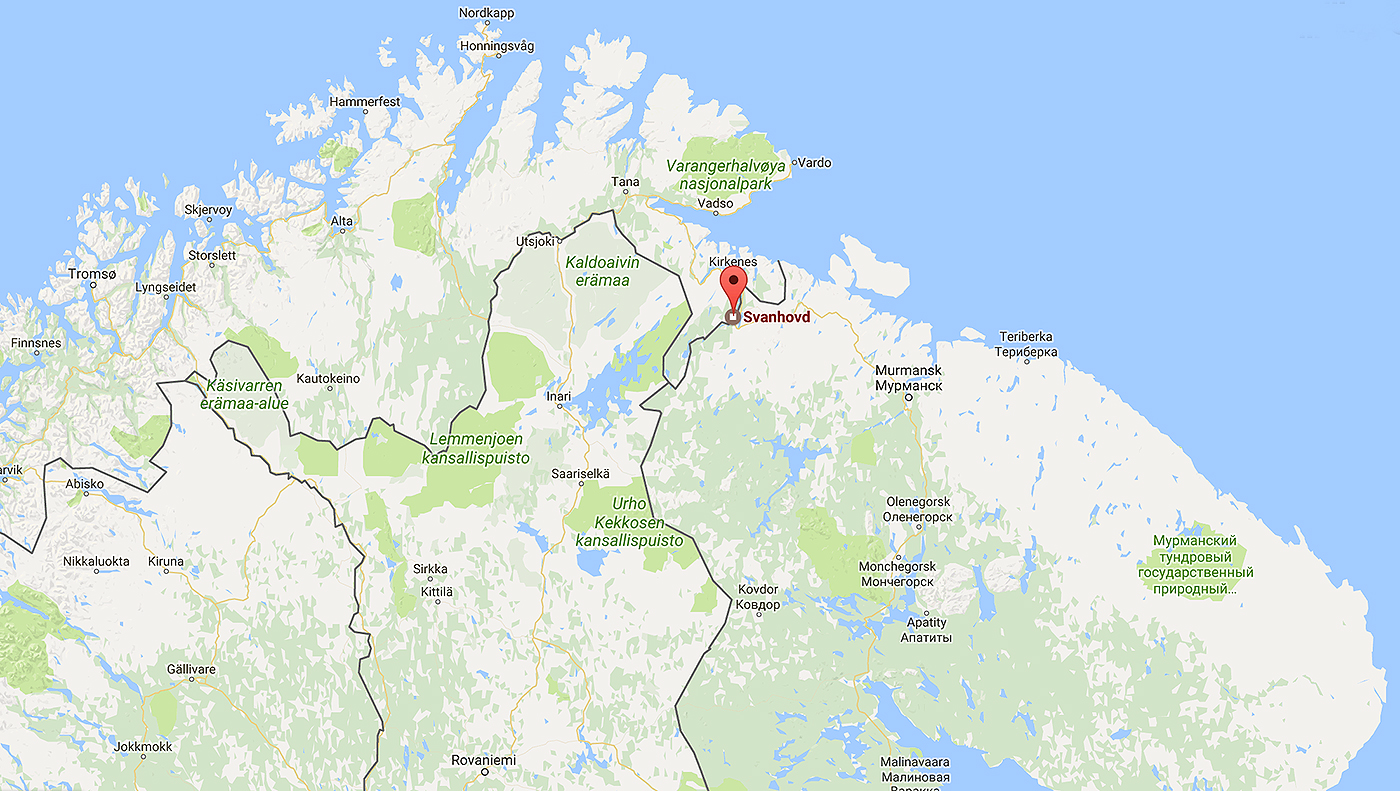

The first detection of the isotope came during the second week of January, via an air sampling station located in Svanhovd, on Norway’s border with Russia’s Kola Peninsula. Within days, air sampling stations as far south as Spain also detected the presence of small amounts of the isotope. The fact that iodine-131 has a half-life of just eight days would point to the release occurring just days earlier, and not being a remnant of a past nuclear event.

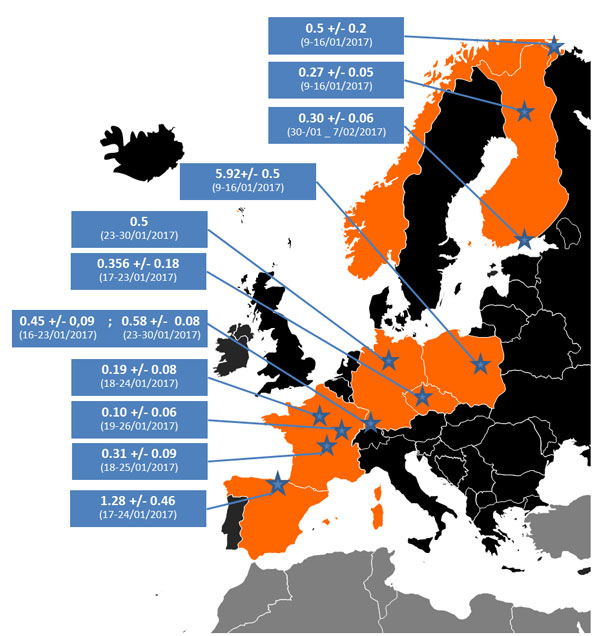

Because of the low levels of concentration, there is no health risk to the public or the environment, at least on a wide scale. By comparison, these recent measurements are roughly 1/1000th the size of what was detected during the Fukushima incident and 1/1,000,000th the concentration found in the nuclear tainted cloud that washed across Europe following the Chernobyl disaster.

Iodine 131 levels monitored across Europe last month (IRIN graphic):

After weeks without answers, the story seemed to pass as a peculiarity, not nearly an unprecedented one at that, until Friday when the US dispatched its WC-135 Constant Phoenix atmospheric testing aircraft to Europe without explanation. The highly unique aircraft are specifically designed to respond to nuclear incidents—especially those that include the detonation of nuclear warheads.

By sampling the air over wide areas and at altitude, the aircraft can provide critical data to better understand the “signature” of a radiation release. During nuclear tests, this can help scientists define what type of weapon was detonated, and, in conjunction with other data, how large the blast was. They can also be used to measure the effects and scale of other radiological events, like the meltdown of nuclear plants. For instance, the WC-135s went to work following the 2011 earthquake that resulted in the meltdown of Japan’s Fukushima nuclear power plant.

WC-135 taking off on a mission (USAF photo):

This leaves us with a number of unanswered questions. The first: What are WC-135s doing up there? Was this a good opportunity for a training sortie and to support scientific endeavors, or is it in response to a specific incident?

You can check twitter to see loads of people claiming this is proof that the Russians have restarted nuclear weapons testing at Novaya Zemlya near the Arctic. That assertion is problematic for a variety of reasons. The first is that we have no corresponding seismic data indicating a nuclear detonation from that region. Some have floated the possibility that a small tactical nuclear warhead may have been tested; once again, this still makes a big boom, and it is not clear if the levels of iodine-131 are indicative of such a test. Of course, politically speaking, restarting nuclear weapons testing would signal a massive shift in Moscow’s nuclear weapons policy.

There has been some talk about even the US restarting its nuclear testing under President Trump, but this is largely speculation mixed with hyperbole. Even though we have seen Russia is willing to migrate away from key weapons treaties in order to obtain niche strategic capabilities, violating the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty would signal a whole other level of aggression and defiance.

A more likely possibility is that some sort of limited nuclear material storage, research, or power generation incident has occurred. Russia uses nuclear propulsion for many of its active submarines as well as its Kirov class battlecruisers and its icebreakers. Russia also uses nuclear power in the arctic region for multiple applications. Not just that, but Russia’s northerly naval bases near the arctic are nuclear graveyards of the Cold War.

The international community has worked with Russia over the last two decades to safely dispose of hundreds of Soviet-era nuclear submarines, but decommissioned hulls and reactor sections still sit idle waiting to be denuclearized and properly disposed of. Many have said that over the decades following the end of the Cold War, these vessels were just an accident waiting to happen. Some of these vessels remain on the Kola Peninsula near Murmansk.

One of Russia’s largest nuclear waste containment facilities, where the reactors of these decommissioned submarines are stored, is also located nearby at Saida Bay. Today, some 80 reactors and their shredded components are stored there in massive casks. Eventually the facility will store 155 junked reactors and their waste. Disposing of such toxic, complex and ungainly machinery is no easy task and comes with its own share of risks.

Photo via Sovfoto/UIG via Getty Images:

The Arctic is also dotted with other Cold War relics that relied on nuclear power to function, these include Russia’s nuclear lighthouses and outposts. And this is just what you can see, below the surface, hulks of sunken nuclear vessels and other waste still pose a major threat to the environment. It is not really a question of if they will do harm, but when.

During the Cold War, Russia dumped all types of nuclear waste in the Kara Sea, including an estimated 17,000 containers and 19 vessels full of radioactive waste. The USSR also pitched 14 nuclear reactors, some with spent fuel rods, into the same body of water and other forms of lower-level nuclear waste was just poured directly into the sea. The Russian submarine K-27, which was scuttled in the Kola Sea, is said to be literally a ticking time bomb. That is just that one area, and other areas in the region, such as the Barents Sea (K-159) and Norwegian Sea (K-278), also have abandoned nuclear submarines and who knows what else lining the sea floor. Even the US left its own portion of nuclear waste in the northern latitudes, such as the once secret reactor at Camp Century, in Greenland, although this is minuscule compared to what the Soviets left behind.

A graphic showing the known nuclear waste and wreckage sites near northern Europe and the Arctic (Bellona.org graphic):

On top of all the Russian nuclear material that is actually rotting in arctic, there are also nuclear power, ship maintenance, and research stations that also dot Russia’s northern reaches.

With all this in mind, if there was a peculiar release of iodine-131 into the atmosphere, it is much more likely to have come from the nuclear wasteland that the Soviet Union created, or from operational reactors in the region, and not from some sort of clandestine atomic testing. That doesn’t mean it is impossible, just highly unlikely. There is even a possibility that it didn’t come from Russia at all, and was leaked by a reactor in Europe or elsewhere. Still, with the Arctic likely becoming a key battleground of the future—a reality that has been spurred by Russian military expansion into the region—and considering Moscow’s great change in geopolitical tone and military stance over the last few years, suspicions surrounding Russia’s true intentions in the region are at an all-time high.

Now we’ll have to wait and see if the Pentagon releases more information on the movements and findings of its WC-135, and if there is yet another new spike in radiation coming from the region. If anything else, this mystery should serve of a stark reminder—and a warning—of what mankind has left behind near the arctic, and how perilous a threat it still poses nearly three decades after the Cold War officially ended.

UPDATE: 2.22.17- The WC-135 Constant Phoenix along with a RC-135 Rivet Joint, as well as tanker support, have taken off on a mission to the Norwegian and Barents Sea. Read the update in full here.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com