Prime aerospace defense contractors are throwing everything they have into the competition to replace the venerable T-38 Talon as the United States Air Force’s next jet trainer. Dubbed the T-X program, this new jet is supposed to bridge the gap between primary training on the T-6 Texan II and the advanced fighters that student pilots will one day fly, such as the F-22 Raptor and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

About 350 jets are envisioned to be initally ordered by the USAF, but that number could grow substantially as export customers emerge—and if the aircraft ends up providing additional duties for the Pentagon. Namely, a version of the T-X, which will be far more maneuverable than the already-nimble T-38, could find a serious niche in the adversary support mission.

This is especially true as fifth-generation stealth fighters continue to fill USAF flight lines. These aircraft are more expensive to fly and maintain than many of their geriatric fourth-generation counterparts; flying them against one another for basic training, thus, is a huge waste of money.

This massive demand for third-party adversary support is something I predicted years ago, and now we are seeing large growth in the marketplace and the inclusion of T-38s in fighter wings flying F-22s. You simply don’t need an F-35 to act as a target for another F-35. The USAF is coming to terms with this reality, and the expansion of the F-35 fleet will only force the subject further into the limelight.

With few major aircraft contracts out there these days as the Pentagon aims to cut the number of different types of aircraft in service, the T-X represents a massive opportunity for manufacturers to stay in the high-performance tactical aircraft game. With this in mind—and seeing that the T-X requirements are for a highly-agile trainer, which shares many charistics with front-line tactical fast jets—some of the competitors have gone all out in an attempt to bring “clean sheet” designs to life. Of the competitors, Northrop Grumman-BAE and the Boeing-Saab consortiums will put forward entirely new designs.

Originally, Northrop Grumman intended to run with an updated version of BAE System’s Hawk T2 trainer, but that idea was axed when it was clear that the 40-plus-year-old design would not meet the USAF’s lofty performance requirements. Following this change in strategy, Northrop Grumman’s design process became especially secretive—although it was widely known that Scaled Composites, a company that dramatically changed aviation under legendary aircraft designer Burt Rutan and was acquired by Northrop Grumman in 2007, would be heavily involved.

Scaled Composites effectively led the industry into the world of large composite aircraft structures and rapid prototyping, although this technology has become widespread throughout the aerospace industry in the last few decades. Still, the name Scaled Composites carries a lot of cache, and they usually are at least one step ahead of the competition when it comes to aerospace technology.

This unique Scaled Composites-Northrop Grumman heritage was clearly evident when the company’s T-X broke cover on Friday. Dubbed the Model 400, the aircraft looks like a modernized, composite hybrid of the T-38 Talon and the F-20 Tigershark. It packs a single F404-GE-102D engine, a derivative of the same engine used in the F/A-18A/D, the JAS-39A/D (Volvo RM12), the F-117A, and India’s Tejas light fighter—as well as Lockheed’s T-X competitor, the T-50A. The engine/airframe appears to lack an expanding nozzle usually indicative of an afterburning capability, so either Northrop-Grumman’s design is made to perform on dry thrust alone, or it will add afterburning capabilities on a later prototype. That said, it is also possible that a simpler, internal nozzle could be built into the design, which could enhance aerodynamic performance, save weight, and lower costs.

It is likely that BAE Systems and its partners (L-3, primarily) will provide much of the aircraft’s avionics systems integration, including its high-end synthetic tactical training suite. Decades of developing this system for the Hawk may pay off huge for the T-X competition, as the system is proven and can save money in more abstract ways than flight hours and sustainability costs alone.

Ultimately, this design can potentially be pitched as an entirely new aircraft while still leveraging Northrop’s hugely successful T-38 Talon lineage—a strategy that has proven itself in the past. Take the Super Hornet; it is effectively an all-new design, but was easily pushed through the Pentagon, the White House, and Congress because it could be pitched as a cost-effective “evolution” of an existing (and proven) aircraft. A “composite T-38” could accomplish this as well. If the jet’s price tag is also appealing, it could be very tough for its competitors to beat.

It is thought the Model 400’s official roll-out and first flight will occur sometime early next year. In the meantime, Lockheed has been touting its highly-mature T-50A, while Raytheon and Alenia Aermacchi’s M-346/T-100A is already serving the Italian, Singaporean, and Israeli Air Forces, with Poland to receive its jets soon.

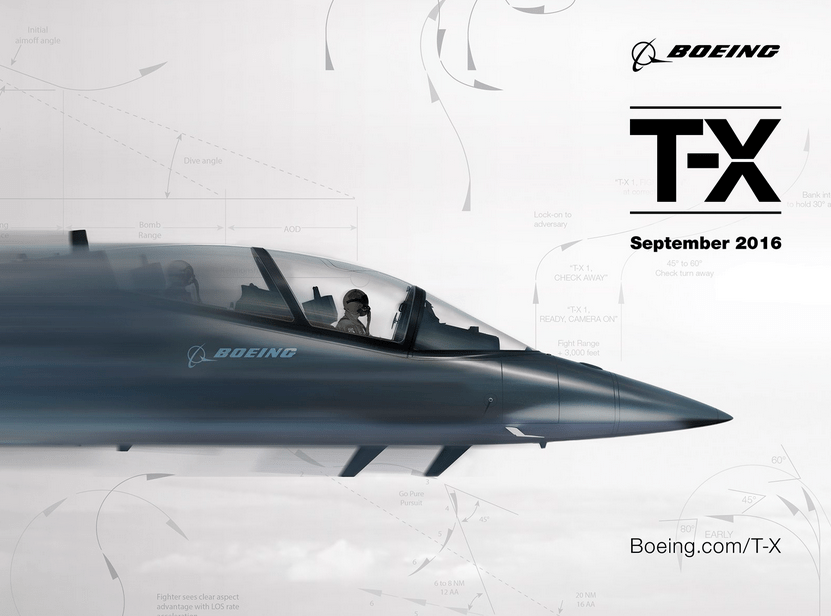

The closest competition to Northrop Grumman’s clean-sheet design route, then, may be the Boeing-Saab consortium. Their new design has only been teased in a few limited renderings, but these two companies are a good match and have proven to be able to build cost-effective, sustainable, and highly-relevant tactical aircraft while staying on budget in the past.

Lara Seligman over at Aviation Week put together this cool little primer on the competition; it’s well worth clicking through if you need to be brought up to speed.

With billions on the line, the T-X competition will be a literally a fight-to-the-death for some of the aircraft involved. Clean-sheet trainer designs that lose competitions don’t have a great track record of going on to great things.

The USAF is seeking to release its final RFP by the end of the year and aims to make an award in 2017, although that date seems optimistic. Initial operational capability is slated for 2024, but depending on the state of the USAF’s budget and the development of the chosen trainer, this could also slip. Then again, with the rise of unmanned aircraft and the great potential advanced unmanned combat air vehicles hold, how many advanced new jet trainers that will supposedly operate for decades to come does America’s air force really need?

Contact the author at Tyler@thedrive.com