Boeing officials have said they aim to start testing new hypersonic weapons capabilities for the B-1B Lancer bomber in September next year, although it’s unclear at this stage what these trials might consist of.

While the U.S. Air Force continues with plans to withdraw the B-1, most recently sending 17 of the 60 remaining aircraft to the boneyard, the service is meanwhile pressing ahead with plans to arm its remaining Lancers with new hypersonic weaponry. Increasingly, the planned weapons upgrades for the B-1 are seen as a means of not only keeping pace with worrisome developments in Russia and China, but also of providing cover for the B-52H Stratofortress fleet as it undergoes its own enhancements, including an ambitious re-engining program that will see fleet availability reduced while underway.

Details of the ongoing plans to turn the B-1 into a ‘missile truck’ for new hypersonic weapons emerged recently during a talk by Boeing officials at the Military Affairs Committee of the Abilene Chamber of Commerce, the business interest organization in the Texas city that’s also home to an operational Lancer unit, the 7th Bomb Wing at Dyess Air Force Base. The results of that meeting were published by the Abilene Reporter-News daily newspaper and shed light on the current plans.

The Boeing officials outlined how the surviving B-1 fleet will be enhanced until the type’s ultimate retirement in favor of the forthcoming B-21 Raider, a new-generation stealth bomber, the latest progress on which you can read more about here.

The Air Force expects the first operational examples of the B-21 to enter service at another B-1 base, Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota, sometime in the mid-2020s, followed by Dyess Air Force Base, and Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, the latter being the home of the B-2 Spirit fleet. With that in mind, the B-1 fleet at Ellsworth could be expected to serve for another decade or more.

The introduction of hypersonic missiles is planned as a key component of keeping the B-1 relevant until then. Several experimental air-launched hypersonic missiles are already under test, albeit with mixed results during initial trials.

According to Robert Gass, former Dyess Air Force Base commander turned strategic development and investment manager for Boeing’s bombers program, the B-1 will have its Cold War-era external weapons carriage capability reactivated to accommodate the new weapons. Work to reactivate the B-1’s hardpoints has actually already begun, initially to carry up to a dozen more subsonic AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) cruise missiles, or AGM-158C Long Range Anti-Ship Missile derivatives, in addition to 24 more of either of those weapons that fit in its internal bomb bays.

The same basic weapons interfaces are slated to be adapted for hypersonic missiles, too. Gass said that these kinds of weapons are “the next big thing in bombers,” but they are dimensionally big, too, making external carriage preferable, and perhaps even a requirement.

So, what’s next for the B-1? First, it’s important to note that Boeing doesn’t expect it to be cheap to outfit the swing-wing bombers with hypersonic weapons capabilities and the program will have to negotiate defense budgets if it’s to succeed.

Much of the cost will be absorbed by reactivating the long-dormant external hardpoints, which were once intended to carry nuclear weapons, before the B-1 lost this role after the end of the Cold War. The pylons were then disabled as the aircraft was made compliant with New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) regulations.

While Rockwell designed the B-1 with eight external hardpoints, Ruder said six of these can be reinstated and used for hypersonic stores. Each of these new Load Adaptive Modular, or LAM, pylons will be able to accommodate two missiles, although the specific type, or propulsion variety, was not specified. Noteworthy is the fact the original external pylons on the B-1B could also carry two missiles each, in this case, the nuclear-tipped AGM-86B Air-Launched Cruise Missile, or ALCM.

According to Ruder, the largest hypersonic missiles will weigh 5,000 pounds and be more than 20 feet long. Again, the missile being described was not named, but these specifications seem to be broadly in line with what little we know about the ARRW. On the other hand, the LAM pylons may also be intended to carry other more conventional weaponry, too, like the aforementioned JASSM cruise missile and its derivatives.

There was no mention of internal carriage of additional hypersonic weapons, although this is something that has been explored in the past by Air Force Magazine, which calculated that a combination of external pylons and common rotary launchers in the internal bomb bays, could potentially carry a mix of up to 31 hypersonic missiles. Based on what the Boeing officials said, it seems that a more modest external load of 12 hypersonic missiles may now be the plan. Prior to such weapons being loaded onto a B-1, however, the LAM pylons themselves would need to be integrated and proven, before captive-carry trials of representative payloads could begin, followed by the release of inert weapons, and finally end-to-end testing.

Gass confirmed that plans call for the B-1 to eventually serve as a launch platform for two kinds of hypersonic weapons: boost-glide vehicles and air-breathing missiles.

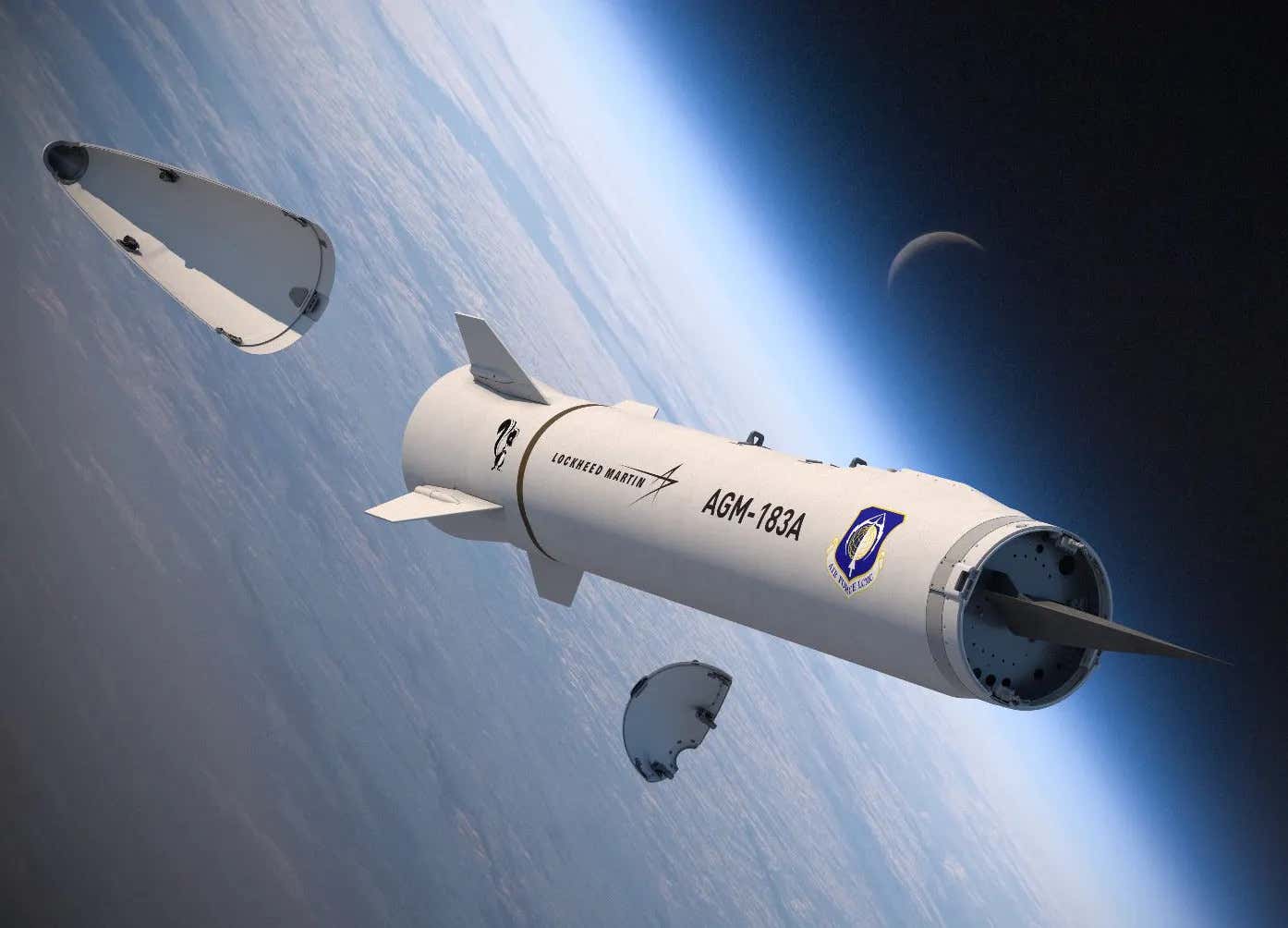

The first category, boost-glide vehicles, suggests the AGM-183A Air-launched Rapid-Response Weapon, or AARW, which is pronounced “arrow,” a hypersonic missile that we also know will be carried by the B-52. To attain hypersonic speeds, the missile consists of a solid-fuel rocket booster, fitted with pop-out tail fins, and the unpowered boost-glide vehicle. After being propelled to a specific speed and altitude atop the rocket booster, the wedge-shaped boost-glide vehicle continues to its target at hypersonic speed.

The second category, air-breathing missiles, could refer to a development of the Hypersonic Air-Breathing Weapon Concept, or HAWC, a scramjet vehicle that was recently tested, accelerating to a speed of more than Mach 5 after air launch from a B-52. There’s also the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile, or HACM, another program involving an air-breathing weapon that would be suitable for carriage by fighter and bomber aircraft.

Last year, U.S. Air Force General Timothy Ray, head of Air Force Global Strike Command, which oversees all of America’s bomber fleets, identified the B-1 as a candidate to carry both the AARW and the HAWC, although the Boeing officials didn’t identify the proposed weapons by name.

At this stage, none of ARRW, HAWC, or HACM are expected to result in nuclear-armed weapons, with all relying on a conventional warhead initially.

Speaking in Abilene, Dan Ruder, Boeing’s advanced programs manager, reportedly told the audience that hypersonic weapons that in the future could travel at Mach 20 — noting that this is “extremely fast.”

In fact, such a speed seems well beyond the capabilities of the air-breathing HAWC and HACM concepts, both of which are expected to cruise at speeds of Mach 5+. On the other hand, the Air Force has, in the past, said the ARRW would fly at a speed of roughly between Mach 6.5 and Mach 8, which may well be an underestimation. Previously, for example, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) said that the boost-glide vehicle being developed for its Tactical Boost Glide (TBG) program could potentially hit a peak speed of Mach 20. During flight tests in 2010 and 2011, DARPA’s Hypersonic Test Vehicle 2 (HTV-2), another boost-glide vehicle, also reached peak speeds of Mach 20.

Moreover, it’s not clear if Ruder’s Mach 20 comment was in reference to any kind of weapon planned for carriage by the B-1, or if he was making a more general point about the kinds of speeds that are made possible by hypersonic designs in general.

Either way, Robert Gass put forward the fundamental advantages of each approach to hypersonic propulsion, noting that the boost-glide vehicle type offered long-range and maneuverability to evade enemy defenses, as well as not requiring such a large warhead, due to its terminal velocity.

For their part, air-breathing hypersonic missiles would offer the B-1 and other platforms the ability to carry more weapons, since they are smaller and lighter than their boost-glide vehicle counterparts. They also fly deeper within the atmosphere, making a more complicated target for enemy air defenses that are not equipped to counter very high-speed threats. The tradeoff, however, is a weapon, or weapons, with reduced speed and range.

Either way, the standoff capabilities of either type of hypersonic weapons should afford the B-1 more protection, allowing it to launch missiles further from hostile air defenses, at what Gass called a “more survivable distance.” This is of particular relevance as adversaries such as Russia and China continue to bolster their anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities, including the introduction of anti-aircraft weapons with ever-longer ranges.

At the same time, the B-1 itself has had its operating envelope scaled back as a result of wear and tear inflicted in the course of extensive combat operations over Afghanistan and the Middle East. Crews are now forbidden from flying at low altitudes, while total annual flight hours have been restricted, which you can read about more in this past War Zone exclusive. Adding new weapons, with longer standoff range, could help mitigate these factors.

Interestingly, the Boeing officials both presented hypersonic weapons as an area in which the United States is lagging behind its rivals, with the envisaged B-1 modernization seen as a way of mitigating that, at least in the short term.

A graphic presented at the meeting showed Russia, with its 3M22 Zircon naval hypersonic missile to be furthest ahead along the developmental path, followed by China, with its XingKong-2 (Starry Sky-2), which Beijing has described as a hypersonic waverider vehicle. Next comes the United States, together with Australia, with which it is partnering on more than one hypersonic program. Lagging further behind were France (V-Max) and India (BrahMos). There were, however, some discrepancies in that graphic, with the Zircon illustrated by the air-launched Kinzhal, while only the United States/Australia was credited with an air-breathing hypersonic weapon (both Zircon and the hypersonic version of BrahMos are air-breathing designs). Moreover, the two stated leaders in the field are both known to have introduced other hypersonic weapons to service, including China’s ground-launched DF-17 and Russia’s silo-launched Avangard.

While starting tests this time next year would seem to be a fast-paced timeline, it’s in keeping with the desire to catch up with the perceived hypersonic head-start enjoyed by Russia and China. Furthermore, with the B-21 potentially entering service from the mid-2020s, there’s might not be much time left for the B-1 to serve in its planned new role as a launch platform for hypersonic missiles.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com