Remarkable new information has emerged on the fate of the nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Thresher, also known by its hull number SSN-593, the lead submarine of its class, which was lost during trials east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in April 1963. While the official explanation states that the submarine sunk soon after getting into trouble, quickly claiming the lives of all 129 sailors and civilian technicians onboard, a newly unclassified report indicates that one submarine sent to search for it thought that at least some of the crew were still alive around 24 hours after the vessel was determined to have imploded.

The newly released information is found among 600 pages of documents, which constitute the most recent releases of information from the previously classified investigation into the loss of the Thresher. While the Navy began releasing these documents last year, on the orders of a U.S. District Court, these are the most recent. They seem to provide the first evidence that at least some of those searching for the Thresher believed there may have been crew members still alive on the submarine many hours after it was posted missing.

Expert analysis of the latest information has been provided by Aaron Amick, a former submariner and a contributor to The War Zone, in the video below. The pertinent details are found in the official account from the commander of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575), a unique vessel that was the second submarine to feature nuclear propulsion, following USS Nautilus (SSN-571). The Seawolf was one of two submarines involved in the search for the Thresher.

Newly overhauled, the Thresher had been conducting deep-diving tests at the time it went missing on the morning of April 10, 1963. Previous Navy disclosures about this incident have said that the submarine rescue ship USS Skylark detected a high-energy, low-frequency noise, characteristic of an implosion, at approximately 09:18 AM that day. Exactly when this was determined is not immediately clear, especially since the Seawolf was still searching for signs of life more than 24 hours later.

The Seawolf, as well as the Balao class submarine USS Sea Owl (SS-405), had been called to the area after voice communications with the Thresher were originally lost and the two submarines arrived in the course of the following day. Neither was equipped to attempt any kind of rescue, but they were to help search for the Thresher.

The newly released documents describe that, while on its way to the area of interest, the Seawolf noted a possible life vest seen through its periscope, as well as other debris in the water. However, this seems to have been a false alarm that eventually only delayed the submarine’s progress.

Around 10:30 AM on April 11, the submarine finally began diving in the area where Thresher was last noted, listening for any signs of distress. Just over an hour later, according to the report, the SQS-4 sonar onboard the Seawolf discovered a stationary object at a distance of 2,000 yards. The submarine closed in on the target only to lose it once Seawolf passed directly overhead, hiding the contact from the sonar.

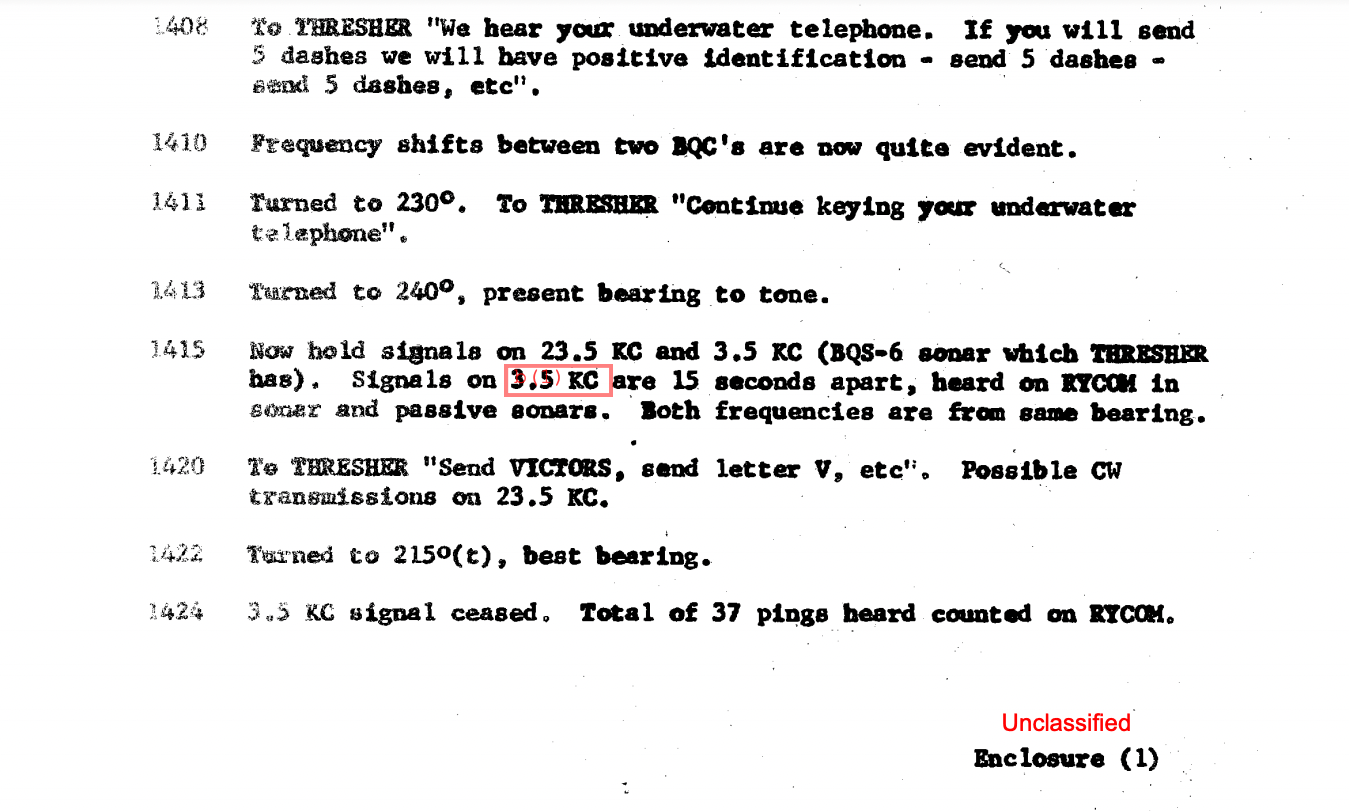

At 12:11 AM, Seawolf heard, via its Rycom receiver, a signal from a distress beacon, or pinger, also known as the BQC. Although it couldn’t yet be confirmed that it was from the Thresher, this was clearly good news, since the pingers, two of which were fitted on each submarine, needed to be manually activated in order to broadcast a signal.

Using its UQC underwater telephone, the Seawolf requested the Thresher turn its beacons on and off. A few minutes later, Seawolf reported “We hear what may be interrupted keying now,” suggesting the beacons were now being switched on and off deliberately.

The Seawolf faced a problem, however, since the sonar activity of the destroyers that were also involved in the search was making it hard to decipher signals coming from what was now assumed to be the Thresher. Furthermore, the Seawolf needed to come near the surface each time its crew wanted to relay messages to other vessels in the search party, or to the headquarters ashore.

A second dive by the Seawolf involved another attempt to communicate with the Thresher. “If you hear my transmission, key your underwater telephone,” was the message sent using the UQC.

At 1:55 PM, the Seawolf reported that it received the emergency beacon tone three times. Five minutes later, another two tones were heard. As of this point, it seems the Seawolf thought that there were at least some people still alive on the Thresher, which would only have been possible had its hull not fully collapsed.

More evidence then came to the crew of the Seawolf at 2:15 PM, when they reported hearing the main sonar from the Thresher. If true, this would have indicated that there were not only survivors aboard the submarine, but that it still had enough power reserves to transmit actively.

At 2:24 PM the report notes that the sonar on the Thresher stopped transmitting, likely after the battery became exhausted. In total, the Seawolf had heard no fewer than 37 pings from the sonar of what it identified as the stricken submarine.

At 2:33 PM, the Seawolf reported it “may hear [a] very weak voice” over the Rycom receiver, but the communications were too garbled to make sense of.

On the third dive, the sonar operators on the Seawolf said they began to hear the telltale banging of metal upon metal, suggesting that someone aboard the Thresher was trying to make contact. “Bang five times on hull,” was the request made by the Seawolf.

Although the Seawolf did not get the five bangs requested, and instead heard groups of three, it did successfully make active sonar contact again, followed by more raps on the hull that were detected at 8:30 PM.

Once again, the Seawolf needed to surface to issue a report, and once again it broke any contact with the Thresher.

A fourth and final effort to find the missing submarine was then made early in the morning of April 12, almost two days since the Thresher had first been posted as missing.

Trying the active sonar and calling the Thresher again on UQC yielded no response. “No answers, no signals,” in the words of the report from the Seawolf. At 5:52 AM the dive was ended.

Eventually, of course, the remains of the Thresher were located on the seafloor at a depth of 8,400 feet. But what happened in the lead-up to this catastrophe is now far less certain. The original narrative had the submarine rapidly sink at the point at which communications were originally lost, but Seawolf, at least, was still trying to make contact with what it thought was the Thresher, many hours later.

While the Navy was compelled to release these new documents, it remains perplexing as to why aspects of this report, at least, were never disclosed before. Ultimately, the Navy thought the Thresher underwent an implosion, which would have made any survivors of the initial accident a near-impossibility. In the meantime, the issue of what actually happened has continued to be controversial.

In his analysis, Amick suggests it might have been a case of the Navy wanting to keep the prolonged demise of the Thresher a secret from the families of those who died. Whatever the reason, we are now, slowly, finding out more about this naval tragedy — the second-deadliest submarine incident on record — but there are clearly many unknowns that remain.

Update, July 15: We have received correspondence from several readers who wish to emphasize the fact that the claims of the USS Seawolf were discounted at the time of the original investigation into the loss of the Thresher. To clarify, that investigation determined that the Thresher sank on the morning of April 10, and was destroyed near-instantaneously by implosion.

It is presumed, therefore, that all the documents that were released earlier this week, relating to the part played by the Seawolf in the scenario, were also taken into account when this conclusion was originally reached. Unfortunately, the available account provides little in the way of detailed assessments of the sounds purportedly heard by the Seawolf but concludes that “None of the signals which Seawolf received equated with anything that could have been originated by human beings.”

Meanwhile, on the message board of the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System Caesar Alumni Association (IUSSCAA), and in response to Amick’s video analysis of the newly unclassified Seawolf documents, Bruce Rule, a naval acoustic and SOSUS expert who testified at the Thresher inquiry, has stated:

“This YouTube video is false, the Seawolf report the presenter is reading from is correct, but the final report certified it was false readings. Seawolf was confused by the active sonar and noise created by the destroyers and the diesel submarine Sea Owl searching for Thresher on 11 April 1963, the day after she was lost. She mistook all sounds from the searching ships as banging on the hull and sonar pings from Thresher. It was a mistake.”

The War Zone has reached out to the Navy for further clarification of the Seawolf report, how it was originally assessed and how the crew of that submarine came to believe that it was possible that crew aboard the Thresher may have still been alive so long after it had been posted missing.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com