The U.S. Army wants a new anti-tank guided missile that is faster than and can hit targets at least twice as far away as the latest, extended-range versions of the BGM-71 TOW family. At the same time, the service wants the new weapon, which would have a maximum range of at least six miles, to be similarly sized to existing BGM-71s so that it can work with existing vehicle-mounted and infantry launchers.

Mark Andrews, the head of the Combat Capabilities Branch of the Maneuver Requirements Division, part of the Maneuver Capabilities Development and Integration Directorate at the Maneuver Center of Excellence at Fort Benning in Georgia, provided the new details about the Army TOW replacement plans at an industry day event on Apr. 7, 2021, according to Military.com. Right now, the new anti-tank missile effort does not appear to have a specific name, with Military.com referring to it simply as a future Close Combat Missile System-Heavy (CCMS-H). CCMS-H is how the Army refers to the current generation of TOWs that are in service now.

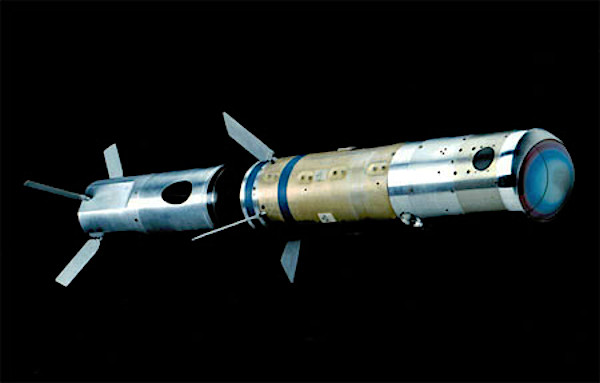

TOW – which originally stood for Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided – is what is known as a semi-automatic command to line of sight missile, meaning the operator has to keep sighting system aimed at the target until the moment of impact. Earlier variants of the TOW missile, which first began entering service in 1970, received course correction data from the launcher via physical wires unreeled from the rear of the weapon after it left the launch tube. The initial generation of TOWs was followed by the Improved TOW (ITOW) in 1978 and the TOW 2 series in 1992, all of which remained wire-guided.

The latest generation of TOWs, which Raytheon, the current manufacturer, began large-scale production of in 2006, have wireless datalinks instead of wires. The Army now refers to them as Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wireless-guided missiles, though the abbreviation remains unchanged.

“We want to increase range to the maximum set possible given the capability,” Andrews, the Combat Capabilities Branch chief, said of the future missile, according to Military.com. “So, if we can get out to 10K [10,000 meters; just over six miles] or plus-10K, we want to be able to achieve that.”

The TOW 2B Aero missile, originally known as the TOW 2B Extended Range, can hit enemy tanks and other targets out to around 4,500 meters, or just under 2.8 miles, according to the Army. Non-extended-range BGM-71 variants that are still in service have ranges closer to 3,750 meters, or just over 2.3 miles.

“We want to retain the current arming distance that the TOW missile has,” he added. Existing BGM-71 missiles all have a minimum range of just 40 meters, or around 131 feet, allowing them to also engage very close-in threats, if necessary.

“We want to be able to shoot on the move and … we want the missile to get there quicker than it currently takes our TOW missiles to [travel] max distances,” Andrews continued. It’s unclear how long it takes existing TOWs to reach their maximum ranges, but the missiles reportedly have a maximum speed of around 1,000-feet-per-second, or just over 680 miles per hour, a relatively modest speed for a missile.

For a weapon like TOW, speed is particularly important since the operator has to keep the launcher pointed at the target through the missile’s entire flight. The longer it takes for the missile to hit its mark, the longer the shooter has to remain in a position where they have a line-of-sight view of whatever they’re shooting at. This can leave them vulnerable, at least to some degree, during that time. A faster-flying missile could also be more capable of defeating emerging active protection systems, as well.

A fire-and-forget TOW variant with an imaging infrared seeker was under development, starting in the 1990s, but was canceled in 2002, ostensibly due to shifting budget priorities. The Army is interested in its future anti-tank missile having some kind of active seeker, as well as two-way datalink and lock-on-after-launch capability. This would allow launch platforms to remain much more concealed, before and after launch, especially if the missiles could be cued to their targets via offboard sensors.

“An adjacent vehicle could take your targeting data and you could pass it to them,” Andrews said. “They could fire the missile because they are best postured to fire that missile.”

Andrews also said that the Army wanted the missile to be more maneuverable than TOW, giving it improved capabilities when engaging threats concealed behind hard cover. This could help simplify the requirements for the warhead, as well.

To be able hit the top of tanks and other heavy armored vehicles, typically an area where they are most vulnerable, the TOW 2B variant notably has a tandem, downward-firing warhead that detonates as the missile flies overhead. However, this precludes it from being used effectively in a direct fire mode against other kinds of targets, which is the reason why other TOW variants with more traditional warheads also remain in service.

It’s interesting to note that the Army, as well as other branches of the U.S. military, spent decades working on faster-flying anti-tank missiles, including designs without warheads that relied instead on the sheer force of their impact to damage and destroy targets. The last publicly known of these projects, the Compact Kinetic Energy Missile (CKEM), which Lockheed Martin was developing, was canceled along with the rest of the Future Combat Systems (FCS) program in 2009. You can read more about CKEM, and other similar developments over the past 40 years, in more detail here.

However, CKEM, and other similar weapons the Army explored in the three decades or so leading up to the end of FCS, were significantly larger than TOW. Combat Capabilities Branch head Andrews made it clear that what the service wants now is something that has the same form factor as the BGM-71-series.

“We have thousands of launchers out there that we just don’t want to have to replace,” he said. Some of those launchers are built into vehicles, such as the Bradley family and ATGM Vehicle variant of the Stryker, and replacing them would require even more substantial changes, too. This could also make it attractive to the Marine Corps, as well as foreign TOW operators, many of which also have specialized vehicle-mounted launchers.

If it works with any existing TOW architecture, the new missile could conceivable also be employed in an air-launched mode, as well. However, Army and the Marine Corps attack helicopters no longer carry BGM-71s, having transitioned completely to the AGM-114 Hellfire.

It’s also worth pointing out that the latest versions of the TOW launcher have powerful electro-optical and infrared optics and offer valuable secondary surveillance and battlefield situational awareness capabilities. Even if the new missile has a fire-and-forget mode, the Army might not be eager to give up these core components of the existing targeting system.

It’s not immediately clear how it might be possible to fit a missile with a range of over six miles into a package similar in size to the existing TOW missile. However, advanced high-grain propellant rocket motor technology has been used in the development of other extended-range missiles, such as the AGM-88G Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range (AARGM-ER), where there is also a demand for the new weapon to be at least close in size to the weapon being replaced.

Whatever the final shape of a future TOW replacement might be, the Army’s renewed interest in this kind of weapon underscores a general interest in new anti-tank capabilities that had emerged across the U.S. military in recent years. The was initially driven primarily by concerns about a potential conflict with Russia following that country’s seizure of Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014. This is actually an area of the world that may be facing an all-new crisis right now. The Army has more recently talked about the general significance of heavy armor, friendly and hostile, in the context of being better prepared for a possible future conflict with China. The ground forces of both Russia and China are already heavily mechanized and both countries have been working on improved armored vehicles of various types.

In addition, anti-tank missiles of various types have conclusively demonstrated their value against a wide range of targets, including helicopters on or near the ground, in a number of recent conflicts. TOW missiles, among other ATGMs, supplied to rebel groups in Syria by various countries, including the United States, were an iconic and often decisive feature of the fighting in that country for years.

As it stands now, the Army’s goal is to at least begin replacing the venerable TOW with this much more capable future missile sometime between 2028 and 2032, at which time BGM-71-series will have been in service for around six decades.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com