The U.S. Navy has announced that its Boeing MQ-25 Stingray unmanned aerial vehicles, which will provide aerial refueling from its aircraft carriers, will be operated by warrant officer with a new specialty designation — the Aerial Vehicle Operator. This comes as the flight-test program for the drone continues to make progress, with a first sortie recently flown with the refueling pod attached.

The establishment of the new Air Vehicle Operator designator for Navy warrant officers was approved by Secretary of the Navy Kenneth J. Braithwaite on Dec. 9, 2020. The service says it plans to train around 450 warrants officers in the new AVO role over the next six to 10 years, across the W-1 through W-5 grades, and send them to the fleet. In the Navy, W-1 is the base Warrant Officer (WO) rank, while W-2 through W-5 are Chief Warrant Officer (CWO) ranks.

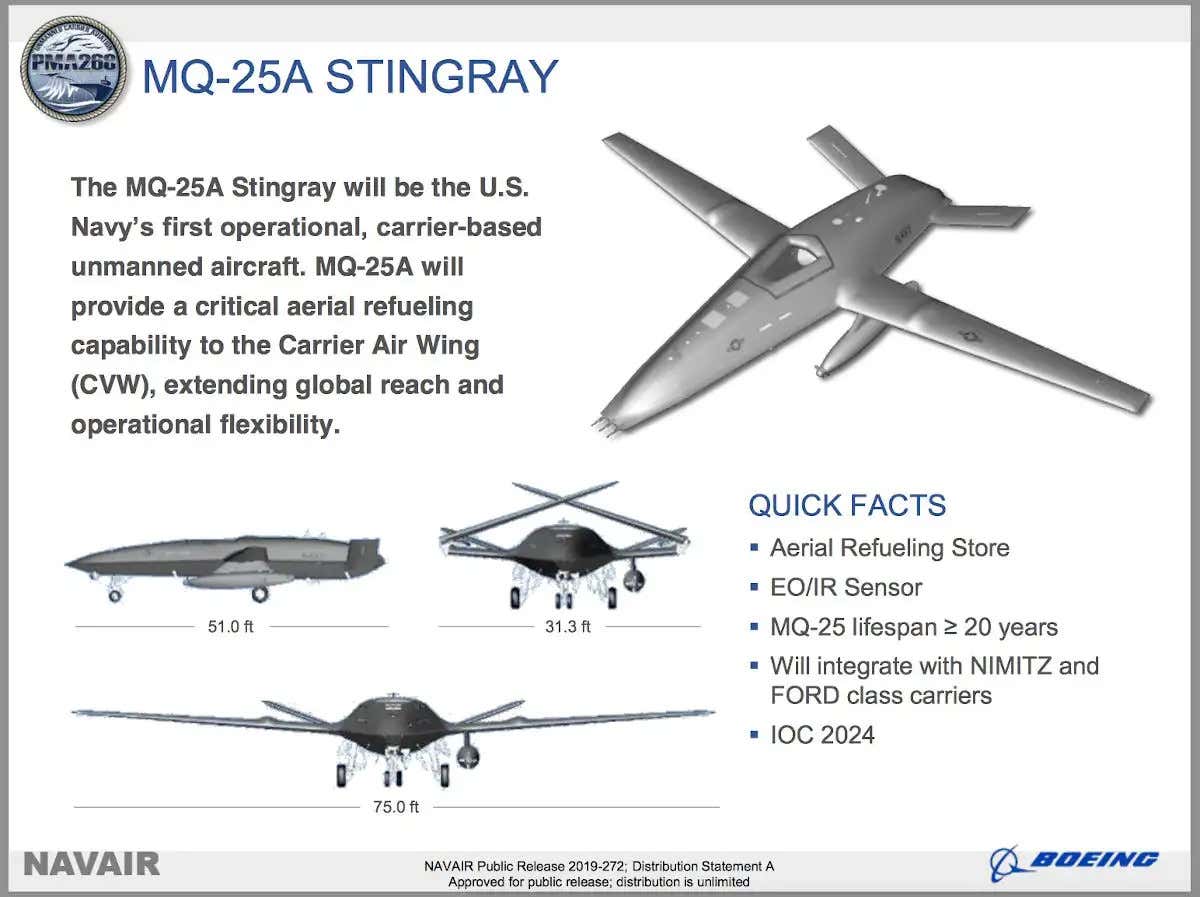

“AVOs will start out operating the MQ-25 Stingray, the Navy’s first carrier-based unmanned aerial vehicle, which is expected to join the fleet with an initial operating capability in 2024,” explained Captain Christopher Wood, aviation officer community manager at the Bureau of Naval Personnel in Millington, Tennessee, in a Navy press release.

“Unlike traditional Navy Chief Warrant Officers, the majority of these officers will be accessed much younger and trained along the lines of current Naval Aviators and Naval Flight Officers in the unrestricted designators,” Wood continued. “However, Naval Aviators and Naval Flight Officers require assignments that progress in tactical and leadership scope to be competitive for promotion, while warrant officer AVOs will be technical specialists and spend their careers as operators.”

The move to designate drone operators as warrant officers was prompted by the fact that, as they progress along their career path, and move up the ranks, they will nevertheless remain technical specialists, undertaking continuous tours. The designator “fits the Navy’s model on how warrant grades are utilized,” the service confirmed. The warrant officer designator is normally used for highly skilled, single-track specialty officers.

Over the next four to five years of this new training program, at least some MQ-25-qualified AVOs will be transferred from other air vehicle types, helping to build up the required knowledge base. Wood confirmed that the “first three to four deployments [will have] a mix of existing unrestricted line and new warrants making up the ready room.”

The path for individuals to operating a Stingray from one of the Navy’s flattops will begin with Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island, where successful candidates will graduate as Warrant Officer Ones. At that point, they start basic flight training followed by advanced training on the MQ-25. They will receive the Navy’s prized “wings of gold” and the 737X designator after they complete basic training.

Beginning in Fiscal Year 2022, the new AVO career will be open to “street-to-fleet” applicants as well as enlisted Sailors, who will then go through the selection process for Officer Candidate School.

While AVOs will be responsible for the day-to-day flying operations of the Stingray fleet, their squadron bosses — commanding and executive officers, as well as department heads of MQ-25 squadrons — will consist of aviators and flight officers.

The creation of the AVO also opens the way to a reconfiguring of other Navy drone-operating communities. The Navy has stated that, in the future, warrant officer AVOs may also operate the MQ-4C Triton drones from shore bases after an initial sea tour with the Stingray. “As the Navy’s footprint in unmanned aerial vehicles increases, so could the scope of the AVO community,” the service says. It is noteworthy that the initial MQ-25 squadron will be based alongside a detachment of Unmanned Patrol Squadron 19 (VUP-19), the Navy’s first MQ-4C Triton maritime surveillance drone unit, at Naval Base Ventura County in California, which includes Naval Air Station Point Mugu.

Last summer, the Navy began the formal process of standing up Unmanned Carrier Launched Multi-Role Squadron 10 (VUQ-10), which will be the first MQ-25 squadron. Plans call for its official establishment date to be October 2021, and that the unit will be located at Naval Base Ventura County. You can read more about these developments here.

There are also tentative Navy plans for MQ-25s to be attached to squadrons flying the E-2C/D Hawkeye airborne command and control aircraft, once integrated within the Carrier Air Wing. It’s not presently clear if, or how, the new AVO designator might affect that.

On the hardware side, too, the MQ-25 is making progress. The existing Stingray demonstrator drone, also known as T1, now looks a whole lot more like the Navy’s future carrier-based tanker after it began land-based trials with an aerial refueling pod carried under its wing.

T1’s 2.5-hour first flight with the aerial refueling store (ARS) installed was conducted on December 9 by Boeing test pilots that operated the drone from a ground control station at MidAmerica St. Louis Airport in Mascoutah, Illinois, where it performed its maiden flight in September 2019. The MQ-25 demonstrator had already completed around 30 hours in the air before it was outfitted with the refueling pod.

The ARS, developed and produced by Cobham, is the same store that’s carried by U.S. Navy F/A-18 Super Hornets that presently fulfill the carrier-based tanker mission.

“Having a test asset flying with an ARS gets us one big step closer in our evaluation of how [the] MQ-25 will fulfill its primary mission in the fleet — aerial refueling,” said Captain Chad Reed, the U.S. Navy’s Unmanned Carrier Aviation program manager. “T1 will continue to yield valuable early insights as we begin flying with F/A-18s and conduct deck-handling testing aboard a carrier.”

The MQ-25’s first flight in tanker configuration is intended to test the drone’s aerodynamics with the ARS under the wing. It’s the first step towards validating the Stingray as an airborne tanker, which will involve further aerodynamics tests throughout its flight envelope, as well as extension and retraction of the hose and drogue assembly to which the receiver aircraft “plugs in” to take on fuel.

“To see T1 fly with the hardware and software that makes MQ-25 an aerial refueler this early in the program is a visible reminder of the capability we’re bringing to the carrier deck,” explained Dave Bujold, Boeing’s MQ-25 program director. “We’re ensuring the ARS and the software operating it will be ready to help MQ-25 extend the range of the carrier air wing.”

Owned by Boeing, T1 was first flown last year and is intended for preliminary test work. It will be followed by full engineering development prototypes that are being completed under a 2018 contract award.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Navy awarded Boeing a contract modification for three additional MQ-25s, bringing the total number of aircraft on order to seven.

Ultimately, however, the Navy intends to procure more than 70 Stingrays, to take on the tanking role from the F/A-18s and more. If all goes to plan, these drones will start to deploy with the fleet in 2024, flown by a new class of Aerial Vehicle Operators.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com