The Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, or CISA, recently published a report titled “Protecting Against the Threat of Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS).” The report comes nearly a year after a string of bizarre “mystery drone” sightings across the American Midwest which remain unexplained to this day. While it does not mention any specific incidents, this new CISA report provides an overview of the growing UAS threat and offers vulnerability assessments and recommendations on how critical infrastructure can be defended against unmanned threats from above.

Unlike many discussions of counter-UAS (C-UAS) approaches, the document does not describe any technologies or methods for jamming or disabling drones, but instead focuses on ways to mitigate the risk of drone attacks without specialized equipment. Recent incidents, such as last year’s mysterious drone incursions over the Palo Verde nuclear power plant in Arizona, underscore just how serious this threat can be and why security forces at sensitive sites need to take heed.

Aside from identifying and protecting against cybersecurity threats, CISA is tasked with “security and resilience efforts using trusted partnerships across the private and public sectors,” and delivers “technical assistance and assessments to federal stakeholders as well as to infrastructure owners and operators nationwide.” One of CISA’s duties is to assess threat capabilities and security gaps through examining emerging technologies both in the near term and long term.

In the document’s introduction, Daryle Hernandez, Director the CISA-led Interagency Security Committee, writes that “Although most agencies do not have the authority to disable, disrupt, or seize control of an unmanned aircraft, there are other effective risk reduction measures they may implement.” Aside from offering a list of potential counter-UAS technologies that could be used to defend against UAS threats, the document provides guidance to security professionals responsible for “facilities in the United States occupied by federal employees for non-military activities.”

While the report notes that many UAS threat events are accidental, it also states that potential adversaries can employ UAS for hostile surveillance, smuggling operations, disrupting governmental operations, or even weaponization. Small munitions or explosives have been employed in drone attacks in recent years, as have suicide drones, and the chance that a UAV attack could include the deployment of biological or chemical agents, even on a small scale, remains a terrifying possibility. One sign of the changing realities in regards to the threat posed by drones occurred in October 2020, when the U.S. State Department issued a warning and reactionary guidance to U.S. personnel in Riyadh about potentially imminent drone attacks.

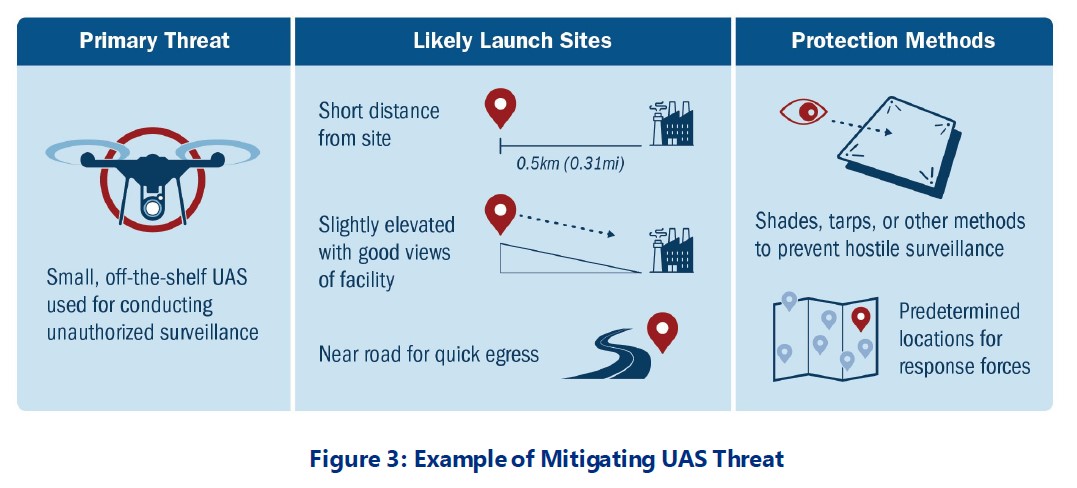

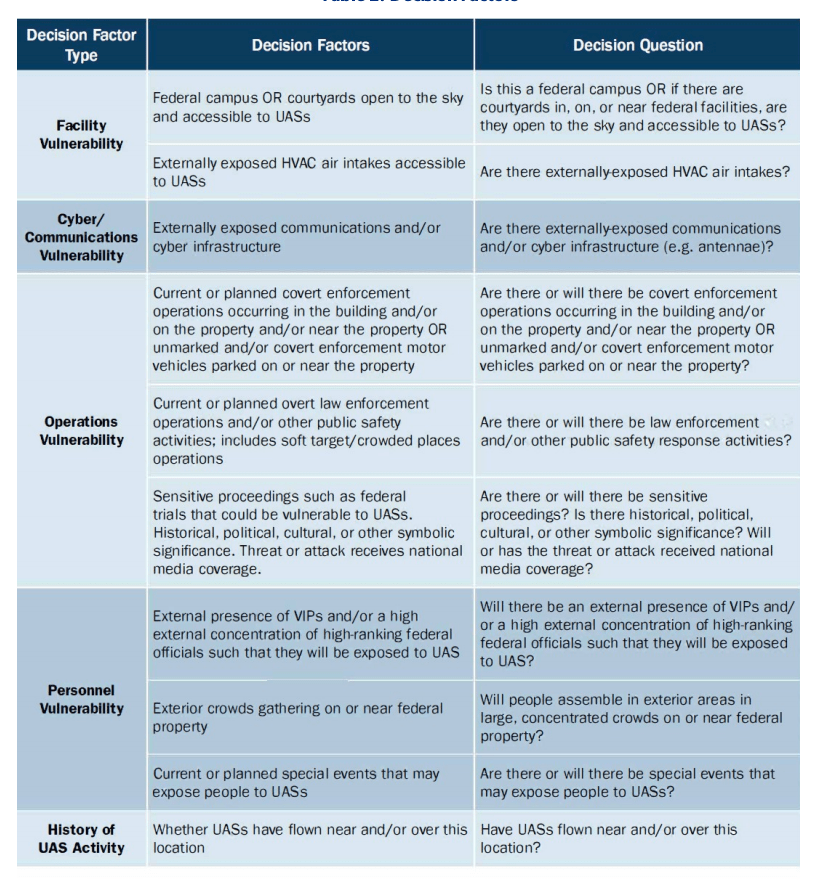

“When considering the likelihood of an adversary using UAS, it is important to consider both the intent and the capability of the adversary, including their desired effect,” the report notes. To that end, CISA recommends facilities conduct site-specific UAS vulnerability assessments to identify what likely target points may be, which critical assets might be targeted first, and how geographical boundaries or terrain features might be used for likely launch or operating points. The report even recommends that facilities become familiar with “nearby UAS clubs” and their associated Launch, Land, and Operate (LLO) sites.

The document addresses the need for sites to be aware that VIPs or crowds can be specific targets of drone attacks, a concern illustrated by last year’s apparent attempted drone assassination of Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro. The report also identifies specific infrastructure that could be targeted specifically by UAS such as HVAC systems, antennas, and cyber infrastructure. CISA even writes that “sensitive proceedings such as federal trials” could be likely targets of UAS attacks, as could any other special events where people are gathered.

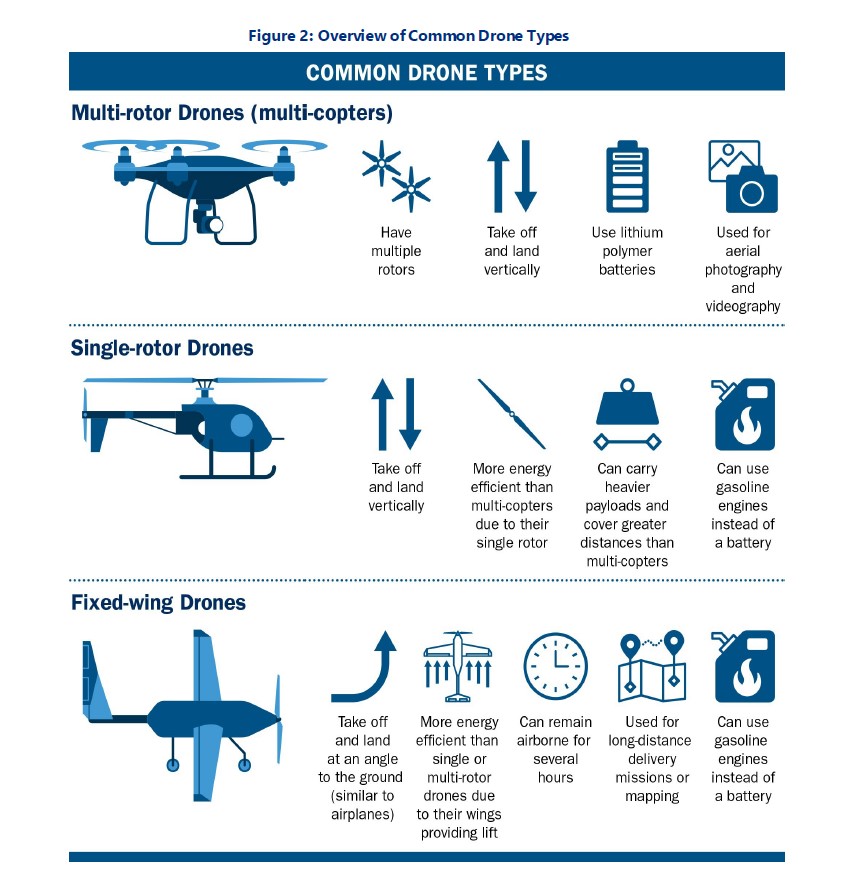

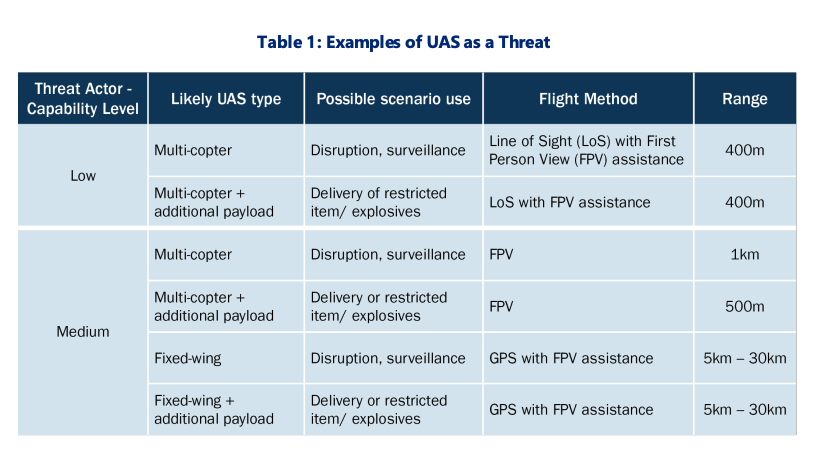

In addition, the report recommends assessing threats based on historical reports of UAV flights near facilities and how the capabilities of existing UAS platforms (such as payload capacities, flight times, speeds, and ranges) should be considered when planning a UAS protection plan. A wide variety of scenarios using various types of UAS are presented along with the capability level various “threat actors” would require to obtain to carry out those scenarios. Off-the-shelf, small multi-copters with first-person view are among the lowest capability levels presented, but these small, inexpensive drones could still be used in surveillance roles and even attacks. This mirrors what we have seen on overseas battlefields and even with the adaptation of specific types of drones that are now being produced formally as weapons.

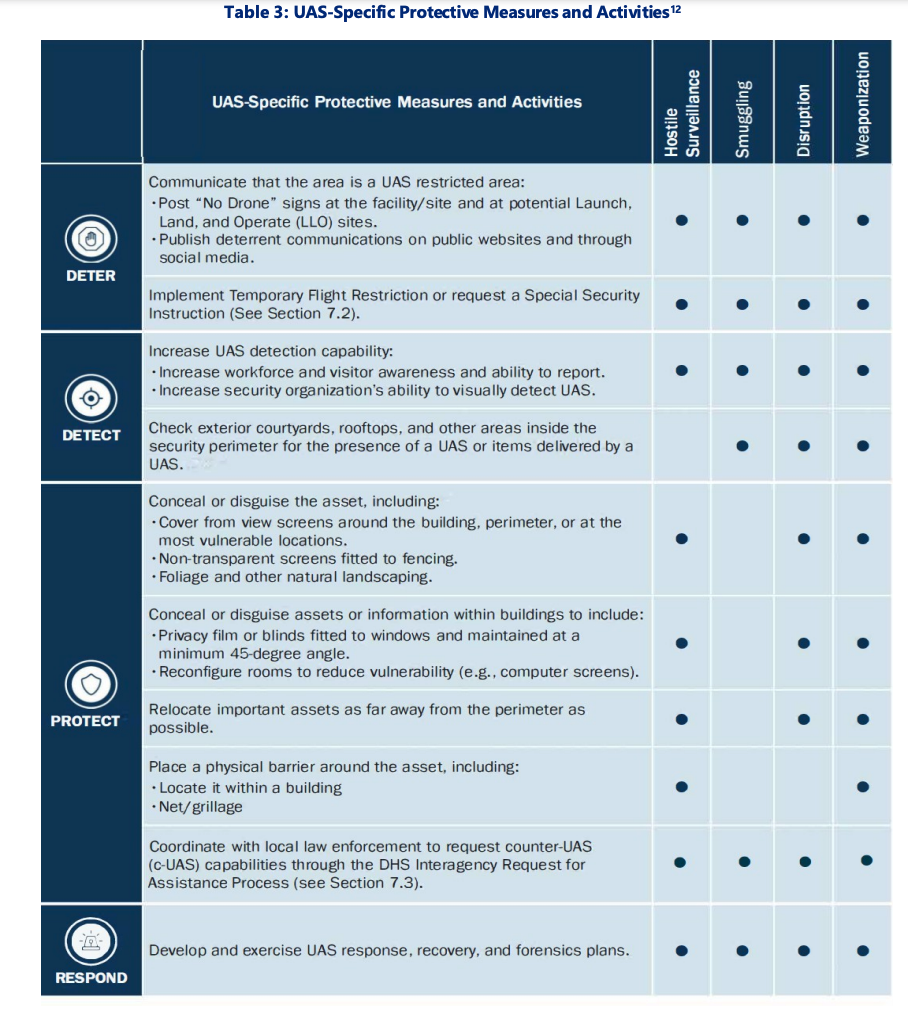

Once assessments are completed, the CISA report offers a variety of strategies that facilities can employ in an attempt to mitigate the UAS threat. As the report notes, “many protective measures designed to mitigate the risks from other threat vectors can also help mitigate the UAS risk. For instance, measures designed to mitigate hostile surveillance, unauthorized access, ballistic attack, and explosive attack will also help to mitigate UAS-specific threats.” These can be as simple as placing signs near sensitive sites, or as complicated as installing specialized netting over sensitive areas.

Some of the strategies the UAS report mentions include:

- Posting “No Drone” signage at facilities and potential LLO sites

- Publishing “deterrent communications” on social media and public websites

- Implementing Temporary Flight Restrictions or Special Security Instructions

- Increasing workforce awareness of UAS

- Checking facilities for UAS or items delivered by a UAS

- Concealing or disguising assets including using non-transparent screens, exterior foliage, and covering any exterior screens

- Using privacy films and blinds at a minimum 45-degree angle

- Reconfiguring rooms to reduce surveillance vulnerabilities

- Relocating important assets as far away from perimeters as possible

- Using nets or grilles as physical barriers around important assets

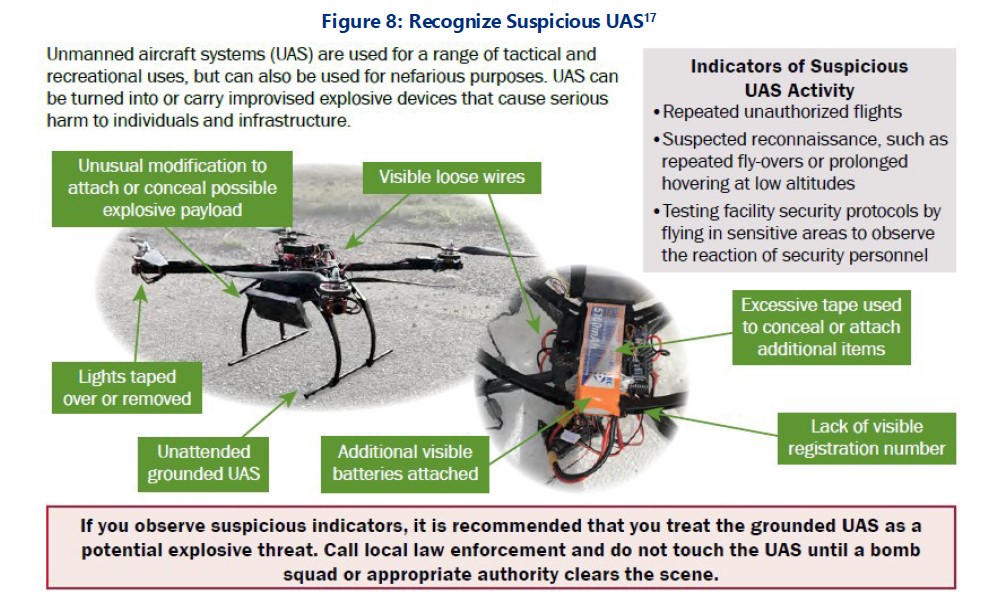

CISA included an infographic in their guidelines that instructs personnel on how to recognize if a drone may have been specifically modified or tampered with for use in attacks. The authors write that visible wiring, concealed or missing lights, or the presence of tape or additional batteries are all warning signs of suspicious UAS activity, as are repeated incursions or prolonged low-altitude hovering.

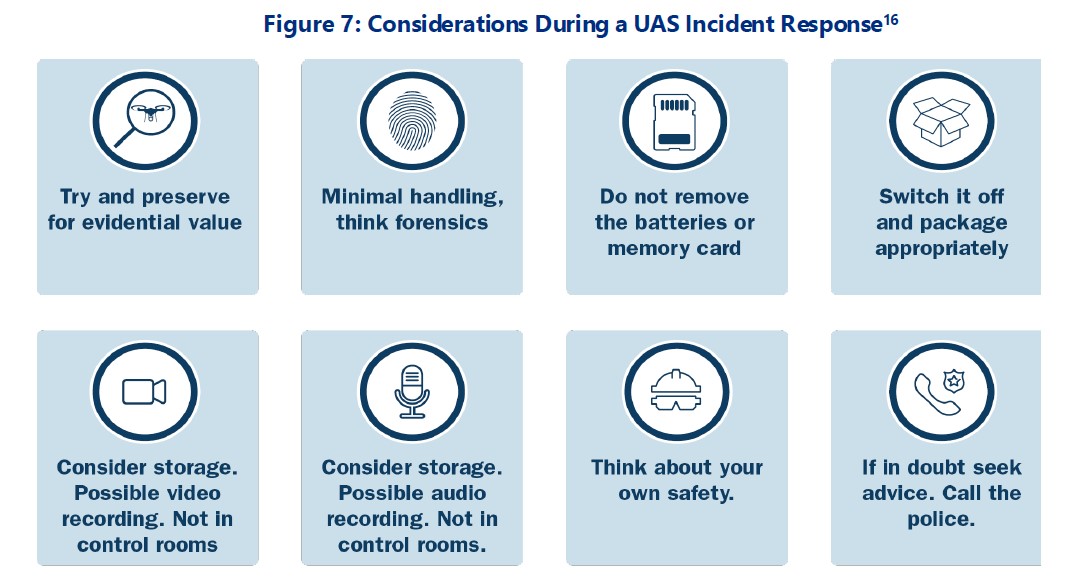

Finally, the report recommends that federal agencies coordinate with local law enforcement to request counter-UAS capabilities through the DHS interagency Request for Assistance Process, and ensure that personnel develop and exercise UAS response plans. In the event there is a UAS incident, CISA offers an infographic on what personnel can do in the aftermath to ensure they do not destroy evidence or harm themselves.

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees CISA. has previously published UAS fact sheets for local law enforcement agencies and critical infrastructure sites, but the depth and breadth of recommendations in the new report underscore just how pressing the UAS threat is becoming. “The ISC details the threat of adversarial use of UAS as an increasing concern in The Design-Basis Threat (DBT) Report,” the document also says.

This latter point about drones being a growing concern with regards to the assessment of Design-Basis Threats, which are “a profile of the type, composition, and capabilities of an adversary” and are “a basis for designing safeguards systems,” is particularly notable. In 2019, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, another agency that is part of the ISC, issued a controversial decision not to require owners of nuclear power plants, such as Palo Verde, and waste storage facilities to defend against drones.

This was based in part on the fact that “[NRC] staff has determined that information gained from UAV video surveillance of an NRC-licensed facility is bounded by the type of information that could be provided by the knowledgeable insider currently permitted in the DBTs.” This new CISA report takes a distinctly opposing viewpoint to the potential threat posed to critical infrastructure by drones.

As unmanned aerial systems become more capable and available, the possibility of rogue operators, terrorist groups, or criminal actors causing immense damage or disruption is growing. Assassination by drone is already a major issue in some areas of the world, and 2019’s drone attacks on Saudi oil fields show just how dangerous and disruptive these types of attacks can be. Even some of America’s most sensitive and critical defensive sites like the U.S. Army’s Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) installations in Guam have had their share of drone incursions in recent years, but luckily, none has resulted in damage.

So far, neither UAS defenses nor law enforcement protocols have caught up with the rapid expansion in drone availability and capability. As our investigation into the “mystery drones” of Colorado and Nebraska showed, even the highest federal government agencies tasked with regulating America’s skies have a difficult time investigating, and even quantifying, let alone responding to reported drone activity. Hopefully, it won’t take a major drone attack on U.S. soil for policymakers to recognize and respond to the rapidly evolving threat accordingly.

Contact the author: Brett@thedrive.com