U.S. President Donald Trump issued a memorandum on Arctic and Antarctic security today that called on the U.S. Coast Guard to explore the possibility of buying nuclear-powered icebreakers, a type of ship that only Russia operates. The same document orders an assessment of what kind of defensive weapons any future icebreakers might carry, specifically to defend against possible threats from “near-peer competitors,” such as Russia or China. The Coast Guard’s tiny existing icebreaking fleets have been in increasingly desperate need of replacement for years now and the service finally awarded a contract for its first new heavy icebreaker, a conventionally-powered design, in decades just over a year ago.

Trump issued the new Memorandum on Safeguarding U.S. National Interests in the Arctic and Antarctic Regions on June 9, 2020. Despite its more general name, the document is centered entirely on buying icebreakers and related issues. The memo directs the Department of Homeland Security, by way of the Commandant of the Coast Guard, and in cooperation with the Secretary of Defense, Secretary of the Navy, and the Secretary of Energy, to conduct a study of the “benefits and risks of a polar security icebreaking fleet mix that … are appropriately outfitted to meet the objectives of this memorandum.” This is part of a larger assessment of icebreaking requirements that the Secretary of Homeland Security, with help from the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Commerce, and the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, is now also instructed to conduct.

The study that the Coast Guard will now conduct will include an assessment of “expanded operational capabilities, with estimated associated costs, for both heavy and medium PSCs [Polar Security Cutters] not yet contracted for,” according to the memo. “This assessment shall also evaluate defensive armament adequate to defend against threats by near-peer competitors and the potential for nuclear-powered propulsion.”

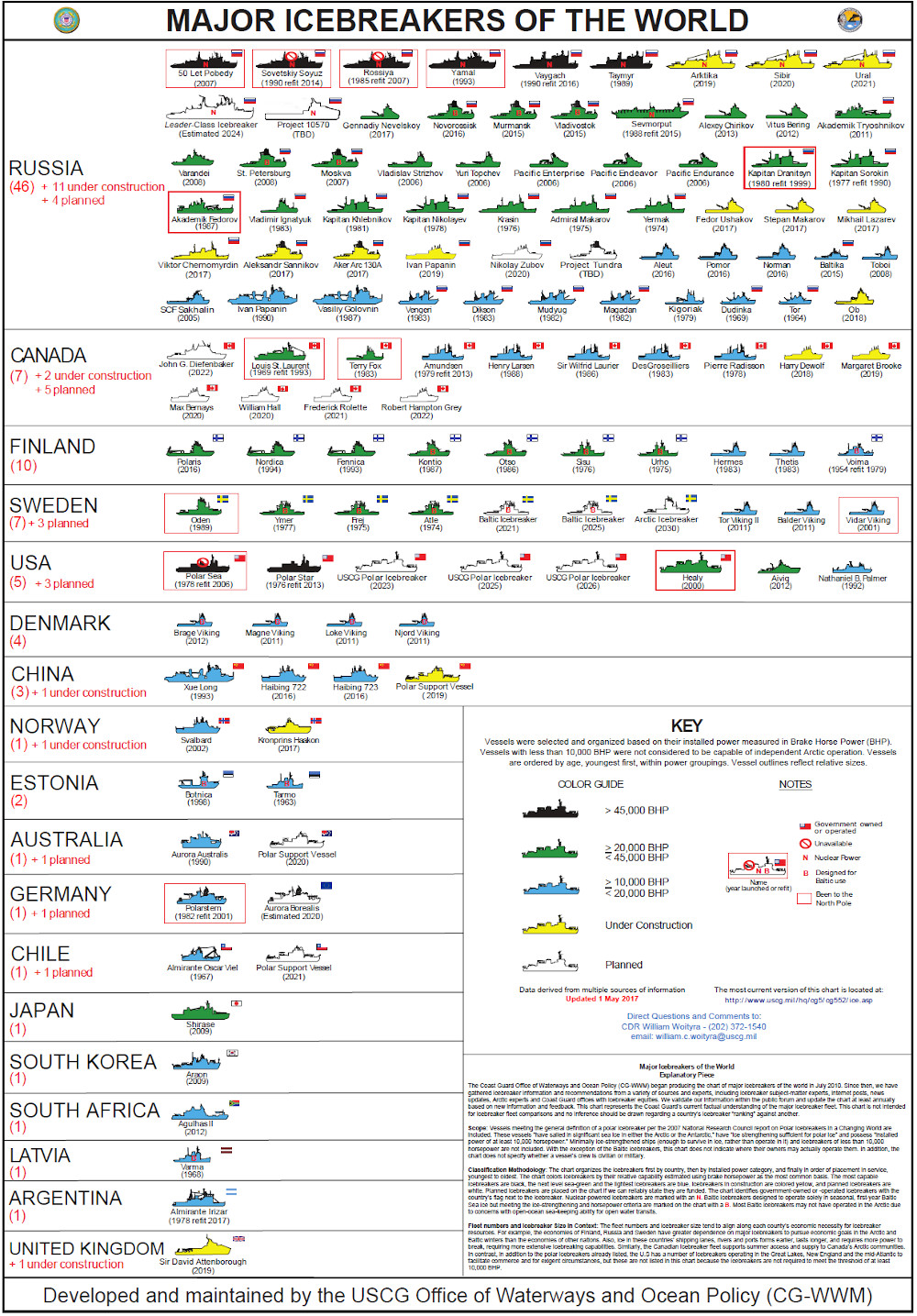

This requirement to explore nuclear-powered icebreakers, almost certainly the reason why the Secretary of Energy will be involved in the study, is unprecedented. Neither the Coast Guard nor the U.S. Navy has ever operated a nuclear-powered icebreaker of any kind. In fact, the only country to do so to date is Russia, which operates four such ships, including the massive 21,000 ton-displacement Taymyr, and is looking to build at least five more, on top of dozens of other conventionally-powered icebreakers and other ice-capable ships. China is now in the process of building its own nuclear-powered heavy icebreaker, as well.

Nuclear-powered ships, of course, have the benefit of not needing regular refueling as is the case with conventionally-powered vessels. A ship with nuclear propulsion could effectively operate for long stretches of time with at-sea replenishment of other supplies and onboard freshwater generation capabilities.

This could enable more persistent patrolling of Arctic and Antarctic areas, which, in turn, could be valuable for maintaining an American presence in those regions. The Arctic, in particular, has emerged as a major area of geopolitical competition as the polar ice cap continues to recede amid global climate change, allowing for new trade routes and the increased exploitation of underwater resources.

At the same time, nuclear propulsion is costly and complex, and employing it on icebreakers could raise concerns about potential operational and environmental risks for ships that will be primarily operating in regions well known for experiencing extreme weather. Environmental activists have long expressed these concerns with regard to Russia’s nuclear icebreaking fleets, as well as its new floating nuclear powerplants. Taymyr alone has suffered a number of radiation leaks over the years.

There is also the possibility that future nuclear-powered Coast Guard icebreakers could find themselves in aggressive confrontations with Russian or other countries’ ships, especially in the Arctic region. This is what is certainly driving the demand to explore potential defensive armament for America’s next icebreakers.

Trump’s memorandum doesn’t mention any specific armament options for the Coast Guard to consider, but its own requirements for its latest heavy icebreaker have included keeping space available for the possible inclusion of weapons of some kind in the future. In 2017, Admiral Paul Zukunft, then-Commandant of the Coast Guard, also told members of Congress that his service was looking at adding both defensive and offensive armament, including anti-ship cruise missiles, onto future icebreakers.

While talk of Coast Guard cutters of any kind, icebreaking or not, armed with anti-ship missiles might seem unusual, the service did upgrade at least three Hamilton class cutters in the 1980s to be able to fire RGM-84 Harpoons. By the mid-1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, these ships had lost this capability, which you can read more about in this past War Zone piece. The entire class, of which two remain in U.S. service, also received additional defenses in the form of 20mm Mk 15 Phalanx Close-in Weapon Systems (CIWS) and Mk 38 25mm automatic cannon mounts.

Much of the rest of Trump’s memorandum covers things the Coast Guard already appears to be doing or has done. The required assessments will examine fleet mixes to include at least three heavy icebreakers. The service has long said that it wants to acquire three medium icebreakers after it gets its trio of heavy types. The difference between the two categories is the thickness of ice they can plow through, with heavy designs being able to get through ice up to 10 feet thick, while the fulls of medium types can manage up to eight feet of ice.

“Use cases in the Arctic that span the full range of national and economic security missions (including the facilitation of resource exploration and exploitation and undersea cable laying and maintenance) that may be executed by a class of medium PSCs [Polar Security Cutters], as well as analysis of how these use cases differ with respect to the anticipated use of heavy PSCs for these same activities,” the memo notes. “These use cases shall identify the optimal number and type of polar security icebreakers for ensuring a persistent presence in both the Arctic and, as appropriate, the Antarctic regions.”

The Coast Guard, at present, only has one operational heavy icebreaker, the USCGC Polar Star, which is aging and prone to major breakdowns, and one newer medium one, the USCGC Healy, that is still decades-old now.

“Based on the determined fleet size and composition, an identification and assessment of at least two optimal United States basing locations and at least two international basing locations,” the memo adds. “The basing location assessment shall include the costs, benefits, risks, and challenges related to infrastructure, crewing, and logistics and maintenance support for PSCs at these locations. In addition, this assessment shall account for potential burden-sharing opportunities for basing with the Department of Defense and allies and partners, as appropriate.”

The Coast Guard’s plan, as it stands now, is to hopefully have taken delivery of all three conventionally-powered heavy icebreakers by 2026. Polar Star could also undergo a service life extension upgrade to keep it in service through at least 2025. There is no firm schedule yet for acquiring the additional medium icebreakers. Trump’s memo says there needs to be “a ready, capable, and available fleet of polar security icebreakers that is operationally tested and fully deployable by Fiscal Year 2029,” by which time Polar Star and Healy are both expected to be retired.

Trump’s memorandum requires the Department of Homeland Security and the Coast Guard to submit their respective reports to the President, by way of the Director of OMB and the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, within the next 60 days. So, it may not be long before we learn whether America’s icebreaker plans have changed to include the purchase of its first-ever nuclear-powered types.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com