Russia reportedly included a system to distinguish between friendly and hostile aircraft that it built to NATO standards with the S-400 surface-to-air missile systems it has sold to Turkey. The same report claims that the actual coded waveforms that this identification friend-or-foe system, or IFF, uses are kept secure within an attached, but separate Turkish-made cryptologic system that the Russians do not have direct access to.

The U.S. government and other NATO allies have repeatedly raised concerns that Turkey’s S-400s will not be able to work in concert with other alliance air defenses during a crisis and could give the Kremlin access to sensitive information, including details about the stealthy signature of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. The United States kicked Turkey out of the F-35 program earlier this year over its purchase of the Russian air defense systems.

Russia’s Gazeta newspaper published the report about Turkey’s S-400s, which is clearly meant to challenge the concerns that the country won’t be able to integrate surface-to-air missile systems with other allied air defenses, on Dec. 5, 2019. The story says that Turkey successfully tested the IFF system during an initial evaluation of one of its S-400s last month.

Those tests also involved checking the function of the S-400’s radars. The complete systems that Turkey acquired include the 91N6E Big Bird surveillance and acquisition radar, the 96L6E Cheese Board air search and acquisition radar, and the 92N6E Grave Stone fire control radar. Only the 91N6E and the 96L6E, the latter of which was mounted on a 40V6M elevated mast, were visible in pictures and video from the testing, but Gazeta‘s sources said that the 92N6E was also present and active.

Those same sources said that the aircraft flew around the S-400 site at Murted Air Base, located near the Turkish capital Ankara, for approximately eight hours in total. Two of the Turkish Air Force’s American-made F-16 Viper fighter jets, an older F-4E Phantom II combat jet, and an unspecified helicopter, according to Gazeta.

They flew at the radars from various directions and altitudes, including extremely low altitudes and in “dead crater” blind spots, likely a reference to a phenomenon known as the “doppler notch,” which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece. The testing reportedly culminated with a successful simulated engagement of an unspecified target.

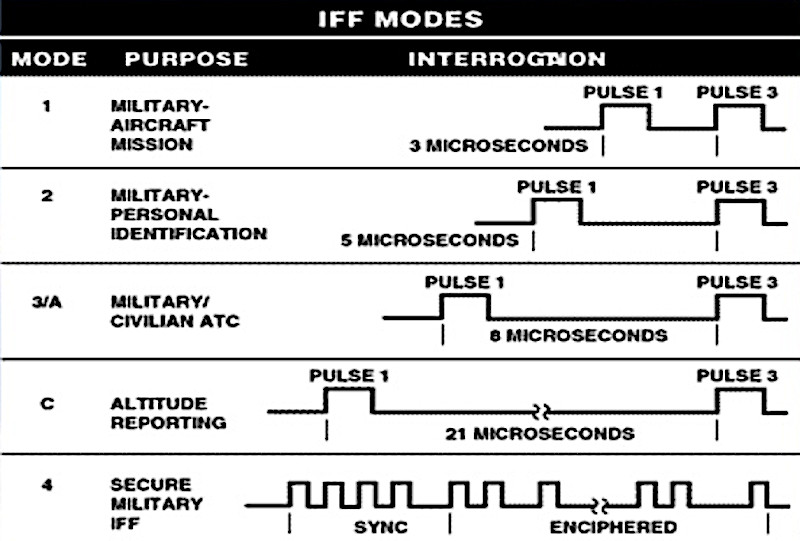

The War Zone had surmised that these tests would also include an evaluation of some kind of IFF capability when they were first announced, but that Turkey’s S-400s are using a Russian made system, known as an interrogator, is particularly notable. The interrogator sends and receives coded signals from friendly aircraft flying above that identify them as non-threatening.

Gazeta‘s story says that the interrogator that Russia built for Turkey’s S-400s conforms to NATO’s Mk-XII IFF system requirement as defined by a set of standards known as Standardization Agreement (STANAG) 4193. This Russian-made system is capable of sending out signals using the current IFF waveform the Alliance uses, also known as Mode 4. Improved Mk-XIIA systems using an updated and more secure Mode 5 waveform are supposed to begin entering service in the U.S. military and other NATO members in 2020.

The Turkish government only reportedly acquired this Russian system in the first place due to delays in an entirely domestically produced alternative from defense contractor Aselsan. Turkey plans to refit its S-400s with its own equipment as soon it’s ready. The clear implication from Gazeta‘s report is that NATO’s interoperability and operational security concerns, at least with regards to IFF codes, are misplaced since the interrogator doesn’t store the codes or have the ability to directly transmit them to a third party.

It’s worth noting that STANAG 4193 is not classified, but NATO itself does not allow its release to the general public, though various websites claim to have copies available for purchase. Russia is also reportedly not working directly with the encrypted waveforms. At the same time, that the Russians were able to build an interrogator to what they feel are NATO specifications does raise questions and concerns about just how closely they worked with Turkish personnel or contractors and the full extent of information that changed hands as a result.

It’s still not clear, however, if the hybrid Russian-Turkish system actually meets the full array of applicable NATO standards, even if it is technically STANAG 4193 compliant. It’s not clear if other members of the alliance would be willing to trust the safety of their aircraft during combined operations to a Russian-built system, regardless. Beyond that, NATO has many more standardization requirements that deal with specific physical elements, including basic and military-specific safety features, and radio and networking compatibilities well beyond IFF systems that Turkey’s S-400 systems may not meet.

Even if the interoperability issues turn out to be relatively minor, it is unlikely that this will address other operational security concerns, especially those that the United States has about the S-400’s radars ability to collect data on the F-35 and whether the Russian might be able to gain access to that information. The U.S. government’s position has been and remains categorically that Turkey can have either the F-35 or the S-400, but not both.

These technical considerations are also moot when it comes to the potential for the United States to hit Turkey with additional sanctions over the S-400 purchase, as well, particularly under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, or CAASTA. Absent the Turkish government receiving a waiver, CAASTA requires the U.S. government to take action, which could include things such as preventing Turkish banks and other business entities from doing business with their American counterparts and blocking the Turkish government from receiving U.S. loans.

President Donald Trump and his Administration, as well as members of some members of Congress, had been holding out hope that there might be some sort of negotiated solution, saying that Turkey could potentially avoid sanctions if it did not “activate” the S-400 radars. The November 2019 testing crossed that red line and now legislators are increasingly calling for the Trump Administration to act. On Dec. 2, 2019, Senator Chris Van Hollen, a Democrat from Maryland, and Senator Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican and staunch Trump ally, sent a joint letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo demanding the implementation of CAASTA sanctions on Turkey.

“Both the Administration and the Congress have repeatedly warned [Turkish] President [Recep Tayyip] Erdogan that his decision to move forward with the S-400 requires the imposition of American sanctions,” the letter stated. “Despite President Erdogan’s recent visit to the White House, he has given no public indications that he is going to change course.”

“The time for patience has long expired. It is time you applied the law,” it said in closing. “Failure to do so is sending a terrible signal to other countries that they can flout U.S. laws without consequence.”

Turkey, for its part, has remained defiant and there are reports that it is now looking to buy even more S-400s. The Turkish government has also expressed interest in other advanced Russian military systems, including Su-35 Flanker-E and Su-57 combat jets and the new S-500 air defense system.

All told, whether or not Turkey’s S-400s have a NATO-compliant IFF system, seems unlikely to protect the country from more American sanctions and further eroding relations with the United States and its other allies.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com