After some seven months, the U.S. military has publicly detailed the results of its investigation into the circumstances surrounding an ambush in the West African country of Niger that left four Americans dead, focusing heavily on failures in the mission planning and approval processes. Not only are many of conclusions presumptive and otherwise difficult to believe, they seem aimed, at least in part, in obscuring how much combat the regional counter-terrorism mission actually involves as a whole.

U.S. Marine Corps General Thomas Waldhauser, head of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), briefed the press on the findings on May 10, 2018. U.S. Army Major General Roger Cloutier, the command’s chief of staff and the individual who lead the investigation, and Robert Karem, Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, joined him. The inciting incident occurred on Oct. 4, 2017, when Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) terrorists attacked a combined force of American and Nigerien personnel near the village of Tongo Tongo, but resulted from activities that began days before.

“The team inaccurately portrayed the concept of operations for the first of three total missions on three and four October [2017],” Waldhauser said in his opening remarks. “Although the evidence from the investigation indicated that this event was neither a standard practice nor commonly accepted, it underscores the confusion at the time over understanding the special operations component CONOP [concept of operations] approval process.”

The general also identified other key findings regarding the force, also known as Team Ouallam after its primary base of operations, a location that The War Zone was first to publicly report the existence of after the ambush. The element, which included members of the U.S. Army’s 3rd Special Forces Group and attached personnel from other U.S. Army units, was improperly prepared for its deployment to Niger before leaving the United States, failed to adequately engage with Nigerien partners ahead of its initial operation, and did not conduct its own internal pre-mission rehearsals.

The Official Narrative

“Taken collectively, these items dealing with Team Ouallam’s preparedness call into question the oversight and supervision provision responsibilities at various levels within the SOCAFRICA chain of command,” Waldhauser added. He said that punishments, as well as awards for valor during the ambush, will follow the investigation, though the public summary of the report assigns no direct blame for the incident.

The general added that he had already made changes to the approved equipment for units in Niger and elsewhere in Africa, including what vehicles that could have available to them. That the team had been riding in unarmored trucks at the time had quickly captured the public’s attention in the aftermath of the incident.

He had also initiated a review of the mission planning and approval processes, as well as the requirements for units before and during deployments to the continent. Other commands, including Special Operations Command, will initiate their own reviews based on the findings to identify any relevant shortfalls in readiness, training, and other policies and report those to Secretary of Defense James Mattis.

Major General Cloutier and his team reportedly traveled to six different countries, interviewed more than 140 individuals – including a Nigerien survivor of the attack and locals in Tongo – collected physical evidence and reviewed reams of other information before producing a report some 6,000 pages long. The official overarching conclusion was that “no single failure” led to the events that occurred near Tongo Tongo.

The summary of the investigation and the remarks at the formal briefing can only be seen as highly critical of Team Ouallam’s actions. It accuses the team leader of hastily copying and pasting details about the newly proposed mission into an existing template, which gave a false sense of plan’s scope.

According to the official narrative, the initial CONOP document implied that the team’s main objective was to meet and engage with local Nigerien leaders, a common practice to form relationships and gather intelligence. In reality, it was a mission to kill or capture a senior member of ISGS, Doundou Chefou, also known by the code name Naylor Road.

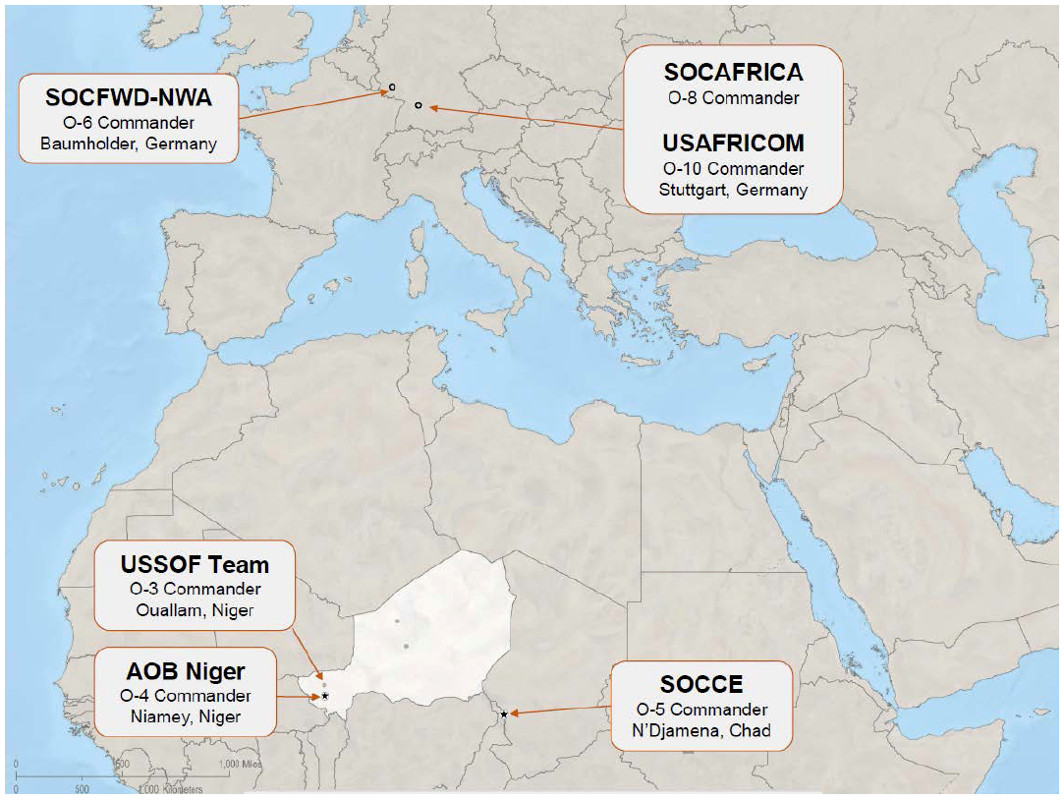

The acting commander of special operations forces in Niger, situated in the country’s capital Niamey, approved this mission, despite knowing its true intention and not having the authority to do so. Yet another special operations headquarters, in neighboring Chad – an element known as a Special Operations Command and control element, or SOCCE – has to approve raids on known terrorists in the region and may end up sending those requests higher up the chain of command to its own superior units, situated in Germany, according the Pentagon’s public summary and the remarks at the briefing.

With the inappropriate orders in hand, on Oct. 3, 2017, the complete force – consisting of 10 Americans, 34 Nigeriens, one U.S. “intelligence contractor,” and an interpreter, according to a separate report from ABC News – moved out to investigate a site to the north near the village of Tiloa, where they thought Chefou was staying. After failing to find any terrorists in the area, they moved to a nearby Nigerien outpost to meet with a local commander, receiving new information about the situation.

At this point, the commander in Niamey briefed his superiors in Chad about the mission. Those officials subsequently ordered a second, larger mission with Team Ouallam acting as a backup force for a heliborne element that would depart from Arlit, which sits hundreds of miles to the northeast.

Weather forced that second team to abort their mission and Team Ouallam proceeded alone, again failing to locate Chefou. It was on the return from that second mission that the group stopped near Tongo Tongo to meet again with other local leaders. The ambush occurred after that so-called “key leader engagement” on Oct 4, 2017.

During that multi-hour firefight, terrorists overwhelmed the Americans and their Nigerien partners, killing Sergeant First Class Jeremiah Johnson, Staff Sergeant Bryan Black, Staff Sergeant Dustin Wright, and Sergeant LaDavid Johnson, all members of the U.S. Army. Two more U.S. personnel suffered wounds and a number of Nigeriens died or were wounded in the incident.

A mix of American, Nigerien, and French forces subsequently arrived in the area. French Mirage 2000 multi-role combat jets and gunship and transport helicopters were particularly instrumental in driving off the ambushers and evacuating the surviving members of the combined force.

During the fighting, Sergeant Johnson got separated from the main group, but he was not captured, as earlier reports had suggested. His body remained missing for two days. You can read more about the exact timeline and particulars of the ambush itself here.

Changing missions or stories?

The investigation’s timeline and conclusion of the events leading up to the ambush are certainly plausible. Special operators in Niger, eager to locate Chefou, who is linked to the kidnapping of American aid worker Jeffery Woodke, may well have wanted to jump on actionable intelligence without having to wait for approval.

However, for this story to hold up, it requires a number of implicit assumptions. Many of the core conclusions from the investigations are simply hard to understand given the overall context.

If the CONOP that Team Ouallam had submitted was misleading, how, as the Pentagon claims, was their commanding officer in Niamey aware of the true nature of the mission? The only explanation here is that this second officer was engaged in a conspiratorial plan to launch an unapproved kill-or-capture mission without seeking approval from his own superiors – something Major General Cloutier made clear his investigators had determined was not the case.

And if the team knew it was heading out on a raid to capture a known and dangerous terrorist from the beginning, why did they appear to only be prepared for the more limited key leader engagements outlined in the CONOP? By all accounts, including a captured helmet camera video that later became public, the American personnel were lightly equipped and in unarmored vehicles without any heavy weapons throughout the entire course of events. The Pentagon investigation showed that some were not even wearing body armor at the time of the ambush.

In addition, the investigation clearly insinuates that if an accurate CONOP had made it to the headquarters in Chad, officials there would have rejected the plan. There is no publicly available evidence to support this conclusion. During the briefing, Waldhauser acknowledged that while this was the first time this particular team had conducted a kill-or-capture mission of any kind, the unit they had replaced had done so in the past.

On top of that, after the team arrived at the initial location near Tiloa and did not find Chefou, the commander in Niamey willingly decided to inform his superiors about a mission he had apparently authorized under false pretenses instead of just ordering the force to return to base without incident. And when officials in Chad became aware of what was actually happening, instead of putting a stop to what would have appeared to be a “rogue” mission, they immediately ordered additional forces into the area. Those individuals also informed their superiors in Germany, who made no attempt to stop the mission.

All told, the Pentagon’s official narrative is the following. An improperly equipped and ill-prepared team of Americans and Nigeriens set out on an inappropriately approved mission. When their superiors discovered the operation already in progress, not only did they not order the unit to stand down, they immediately moved to send additional forces into the area. When that plan fell through, those commanders, who were in regular contact with their own superiors, ordered the original team, poorly suited to the task as it was, to continue with the mission anyway.

This chain of events, if accurate, would seem to imply gross negligence at every part of the chain of command. The alternative, that these decisions somehow occurred without mutual agreement at all levels that the mission was valid or was at least worth pursuing in spite of the initial inaccurate CONOP, strains credulity.

At the same time, if there was a mutual agreement up and down the chain of command, this would strongly seem to contradict the idea that the original CONOP was misleading. If nothing else, it would indicate that these types of mission planning problems were, at least to some degree, a routine occurrence and that commanders would be inclined to take them in stride, regardless of how Waldhauser characterized this particular incident.

Furthermore, reporters at the press conference rightly questioned how it would have been possible to employ limited aerial intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance resources to cover a particular site, as the Pentagon itself says occurred on Oct. 3, 2017, over Tiloa, within the context of key leader engagements and not prompt questions about the true focus of the mission. Waldhauser said that the commander in Niamey had direct control over the still unspecified aircraft at the time, but offered no further details as to how the request for that support had proceeded initially.

The official review of the incident also presents a key detail in the reverse order compared to how it appeared in press reports that emerged in the months following the ambush. The initial indication was that the second team in Arlit had asked for support in its kill-or-capture mission, nicknamed Operation Obsidian Nomad, and that American commanders at some level had decided to retask Team Ouallam with that mission. After that, most of the press coverage seems to align with the Pentagon’s narrative.

A broader operation

Again, it’s not impossible that Team Ouallam went out initially on a mission that the appropriate authorities would have rejected had the known about it in advance or that various details leaked out to the press backward. But in concluding that this incident was somehow a unique confluence of events initiated solely by the actions of one small unit, intentionally or not, the Pentagon has not had to publicly address whether the picture it paints publicly of operations Niger aligns with the reality on the ground or acknowledge any potentially covert components in the country.

“Today, approximately 800 DOD [Department of Defense] personnel are in Niger, a country that is nearly twice the size of Texas, in support of a region-wide, multi-national effort, largely focused on building the capacity of local security forces,” Assistant Secretary of Defense Karem said during the May 10, 2018 briefing. “Of the 800 personnel, only a small fraction are special operations forces engaged in efforts to train and equip our partner forces or provide advise, assist, and accompany support for Nigerien forces.”

Niger hosts the second largest number of American military personnel anywhere in Africa. The bulk of U.S. forces in the country do appear to be dedicated to running drone surveillance missions, and now strikes, from the base in Niamey, as well as working to establish a larger facility in the city of Agadez further to the northeast.

“None of these special operations forces are intended to be engaged in direct combat operations,” he added. “U.S. military activities in Niger are conducted at the request of the host nation.”

This is, almost certainly, a technically accurate description of the overarching regional counter-terrorism mission, nicknamed Operation Juniper Shield. Karem, along with General Waldhauser and Major General Cloutier, emphasized the so-called “by-with-through” approach that is supposed to emphasize training and working with local forces rather than taking direct action.

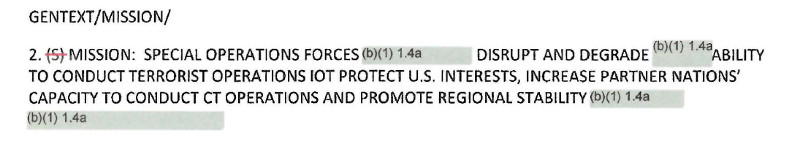

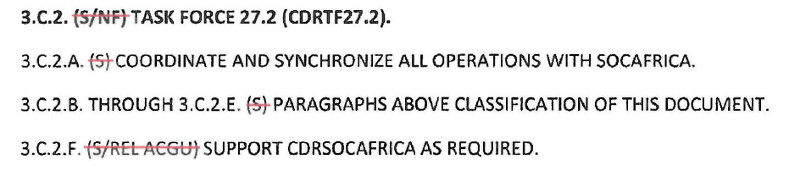

But we at The War Zone know, having obtained a heavily redacted copy of the Execute Order, or EXORD, of that operation via the Freedom of Information Act, that it might not be an entirely honest depiction of the mission at hand. This order, dated 2012, which Karem also cited in his remarks as providing much of the present underlying guidance and authority for counter-terrorism efforts throughout North and West Africa, provides no-nonsense descriptions of the overall mission objective and the responsibilities of key forces.

Special Operations Command Africa (SOCAFRICA) is specifically responsible for “operations, exercises, security cooperation and engagements” in support of the broader campaign plan. This list includes “operations” as distinct from “exercises” and “security cooperation,” which makes it clear that from the very beginning that there was the possibility for American personnel to find themselves on active missions, with or without partner forces. It also says that one of special operators’ main objectives in the region is simply to “disrupt and degrade” terrorists and the unredacted portions make no specific mention of having to do so in cooperation with partner forces.

Even if this were the case, other examples of “advise, assist, and accompany” missions show that this can effectively put American personnel in a combat situation, regardless of the official terminology. In turn, U.S. military forces have in many cases suddenly found it necessary to engage in “collective self-defense” due to their proximity to the action.

Waldhauser emphasized that what happened near Tongo Tongo was a matter of self-defense, as well. He also insisted that appropriate CONOPs make sure to keep American personnel as isolated from potential combat as possible.

“So in other words, if there was a target to go to, our U.S. forces don’t go to that target. they stay – they stay behind, they – it’s a little bit of an art, not necessarily a science,” the general explained, letting slip the inherent flaw in this operating concept. “You can’t really say ‘You’ve got to stay back 500 yards,’ or ‘you can only go this close.'”

A separate task force

In addition, the order names the previously unreported Task Force 27.2 as being a separate force that needs to “coordinate and synchronize” its activities with SOCAFRICA and support that command “as required.” This unit nomenclature is typically associated with elements of the secretive Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), who are almost entirely focused on direct action missions and typically take the lead in doing so even when working with local forces.

As we at The War Zone have previously reported, the operational nickname Obsidian Nomad strongly points to a JSOC mission, as well, based on previous information obtained via the FOIA. Publicly available information suggests that the command is also the entity responsible for operations at the American base in Arlit. That site does not appear in public documents that mention Ouallam and a half dozen other sites in Niger, including four more linked to SOCAFRICA.

There are also unconfirmed reports of the Central Intelligence Agency’s involvement in the operation, which the Pentagon denies. The Juniper Shield EXORD cites a 2005 memorandum of agreement between the Department of Defense and the CIA among its references, but it is unclear how that factors into the operation itself.

It almost certain, though, that the CIA maintains strong relationships with the Nigerien intelligence apparatus. The agency’s activities in the country were central to a controversy in 2003 over reports that then Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had actively attempted to purchase refined, yellowcake uranium, from the country, intelligence that turned out to be fraudulent.

The U.S.-trained Bataillon Sécurité et Renseignement (BSR), or Security and Intelligence Battalion, the Nigerien unit involved in the incident, appears to be akin to similar elite special operations unit the CIA and special operations forces have formed in other countries, such as Afghanistan and Somalia, specifically to provide local support for more active operations. “Intelligence contractor” – the only title we have for another American who was present during the ambush – is a common euphemism for U.S. intelligence personnel, though they could have also been under contract with the U.S. military in the country.

How Task Force 27.2, or the CIA’s paramilitary elements, fits into the chain of command and how its operations intersect with other special operations forces missions in Niger remains unclear. There is a strong indication that it is not uncommon at least for JSOC to work with the publicly acknowledged special operators in the country.

That the so-called “white” and “black” sides of the mission can so easily find themselves in the same operational space raises serious questions about whether the U.S. military has adequate forces and other resources to conduct its riskier missions in Niger or elsewhere in the region – something we have already questioned given the reliance on contractor-operated planes and helicopters for casualty evacuation and personnel recovery missions. It also suggests that units ostensibly tasked with non-combat training and advisory activities can quickly find themselves in combat, regardless of their stated mission with little in the way of outside oversight.

Is anyone paying attention?

U.S. lawmakers got their own closed-door briefing on the investigation into the ambush on May 8, 2018. Many of their responses only further support the idea that the actual scope of Operation Juniper Shield, and activities in Niger specifically, is or was broader than publicly understood.

“That was a very explosive briefing,” Tim Kaine, a Democrat Senator from Virginia said afterward. “I have deep questions on whether the military is following instructions and limitations that Congress has laid down about the mission of these troops in Africa, and I’ve had those questions, and I think this hearing raised a lot more in a pretty explosive way.”

Kaine also suggested that the public face of the mission in Niger was “a fig leaf” that “raises questions about why people are hiding from us what they’re doing.” There is, so far, no evidence that the Pentagon has been concealing the true nature of operations in North and West Africa from members of Congress, including those was the mandate to oversee such activities and who can request classified updates at any time.

What the situation does highlight is the still amazingly broad latitude the U.S. military has to conduct operations around the world under the authority granted in the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force, or AUMF. Congress hastily passed that law in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which allows the Pentagon to launch missions anywhere against the Al Qaeda terrorist network, as well as largely undefined “associated groups.”

ISGS is composed of individuals who had been part of Al Qaeda’s franchise in North and West Africa, went independent for a time, and then refused to join their brothers in arms who re-pledged their allegiance to that global terrorist network. The Pentagon has already cited the AUMF as the legal basis for operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria and its franchise in Libya and almost certainly applies that same logic to operations against the group in and around Niger.

Niger is under threat from or otherwise situated near areas where various other groups operate, as well, making the situation even more complex. The high fluid nature of those organizations and their allegiances call into question whether their motivations are at all global rather than local, as well as whether the U.S. military’s broad counter-terrorism strategy is truly applicable in containing them or addressing the underlying grievances that keep them in business.

Within the halls of Congress, it is much more likely that lawmakers are just now waking up to what’s been going on across Africa for nearly two decades as a result of that law, if they weren’t actually aware already, and are beginning to question the basic logic of the operation. After the ambush, Senator Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican, stated that he had no idea that there were nearly 1,000 American troops in Niger, despite being among those legislators most specifically charged with knowing these details as a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Critics have long questioned whether the AUMF is too broad, effectively giving the U.S. military a blank check to make connections between Al Qaeda and virtually any other terrorist group in the world based on even the most tangential connections. Congress is now set to debate a new AUMF to give proper legal authorization to various counter-terrorism activities around the world.

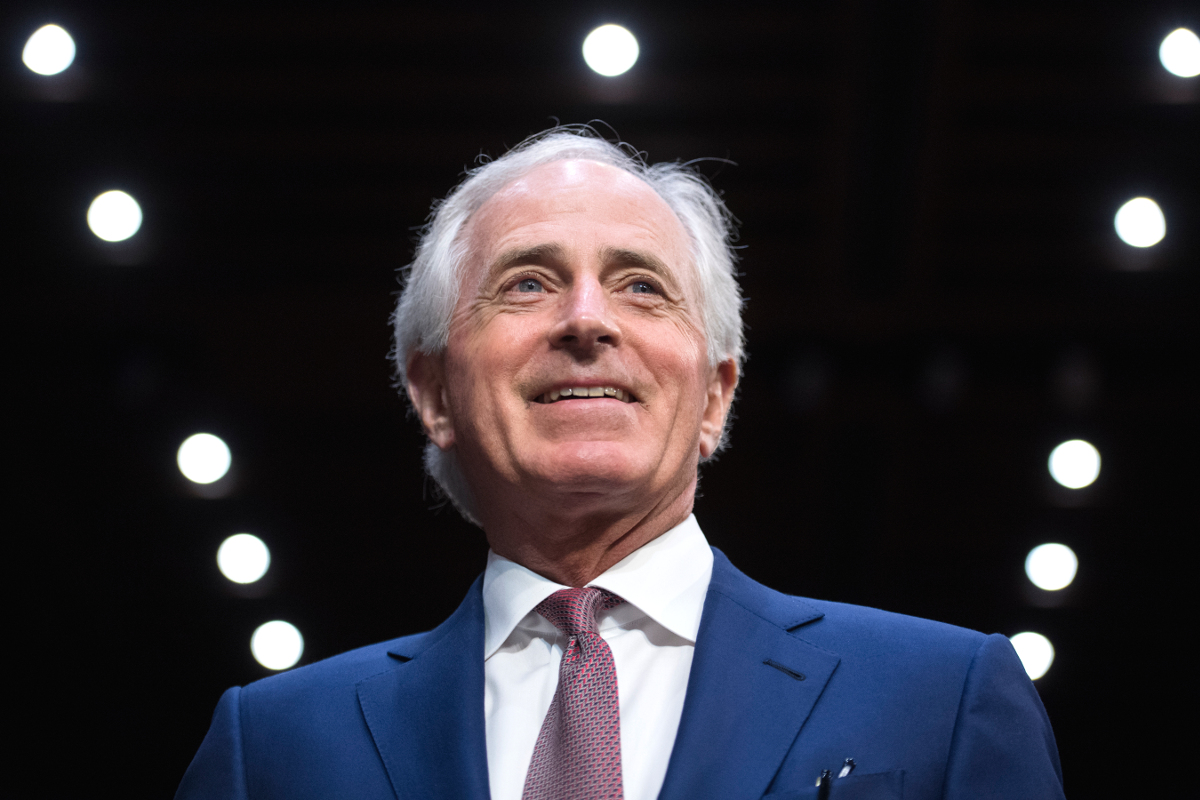

The growing concern, however, is that this will only enshrine the existing status quo and reduce the ability for Congress, and by extension their constituents, to challenge the validity of those operations. The proposed legislation authored by Tim Kaine and Republic Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee does not fundamentally change the underlying language of the AUMF and only expands the number of groups the Pentagon can legally target anywhere. It’s not clear if this legislation will survive the latest revelations about Niger.

“After the hearing yesterday we had huddled,” Kaine added after the classified briefing. “We are going to figure out a way that the story will be told and that people will be held accountable.”

In the meantime, though, American military personnel continue their activities in Niger. Waldhauser says he has already initiated processes to improve the mission approval process and issues guidance to emphasize the “by-with-through” approach.

But it’s not clear whether this will truly change the operational environment or just place a new emphasis on avoiding future situations that could drag U.S. military activities in Africa back out into the public eye.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com