As the U.S. military works to implement a new strategy in Afghanistan and counter resurgent Taliban insurgents and various terrorist groups, much of the focus has been on a surge of American air power into the fight and talk of thousands more troops heading to the region. In the latter case, any newly arrived U.S. Army personnel, as well as those already in the country, along with U.S. soldiers elsewhere in the world, such as those holding the line in Europe, will likely be making use of something of a forgotten weapon in the service, the recoilless rifle.

In September 2017, the Army revealed it was in the process of signing a deal with Swedish defense contractor Saab Bofors Dynamics for more than 1,100 M3E1 recoilless rifles, also known as the Carl Gustaf. In addition, the service was working on making sure that the weapons would get to units as quickly as possible thereafter.

“The current system that the Army uses is the AT4, which only allows soldiers to fire one shot, and then they have to throw the system away,” Randy Everett, the project manager for Foreign Comparative Testing (FCT) at the U.S. Army Research, Development and Engineering Command, said at the time. “With the M3E1, soldiers can use different types of ammunition which gives them an increased capability on the battlefield.”

The M3E1 is an 84mm recoilless rifle, meaning that the weapon allows some of the propelling gasses to escape out of the rear as it fires. These counteracting forces reduce recoil normally associated with bigger guns, though these weapons aren’t truly “recoilless.” They also have a significant and dangerous back-blast, which means troops can’t fire them indoors without specialized ammunition. At present, there is only one special “confined space” round available for the weapon, which is an anti-tank type.

The weapon, which Saab also calls the M4, uses titanium and other lightweight materials to keep its overall weight at just more than 15 pounds. It’s approximately 6 pounds lighter than the old M3 model. It’s also more compact than the previous version at nearly 3.3 feet in length.

The Army’s M3E1 will use a standard telescopic sight, but could accommodate a computerized sighting system in the future. Existing units, which incorporate laser range finders and ballistic calculators, could help troops engage the enemy faster and more accurately, especially when unit different ammunition with different flight characteristics.

The forward grip is wired up so troops can change the settings on certain ammunition, such as changing between an impact and delay fuze, before deciding to fire. Most importantly, the launcher is reloadable and Saab offers a wide variety of different ammunition types so that troops can quickly take on various targets with the weapon.

There are anti-tank rounds with shaped-charge warheads, as well as standard high explosive projectiles, white phosphorus smoke shells, and illuminating flares. The Swedish company also makes a round specifically for busting through concrete walls and other hardened structures, as well as a “close in protection” type that fires 1,100 small metal darts, called flechettes. There’s even a thermobaric round that can be especially deadly against enemies in tight spaces, such as caves, with its large over-pressure blast.

Some rounds have programmable settings, allowing certain types to explode above enemy personnel, showering them with deadly shrapnel, or delay their detonation until after the projectile has broken through a wall or other obstacle. Saab Bofors Dynamics, in cooperation with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), is also looking at the possibility of developing a precision-guided round.

In service with dozens of countries already, including many NATO members such as the United Kingdom, it will also make it easier for Army units to train together with allies and partners. American forces may even be able to better share logistical resources if necessary.

But despite the clear utility of such a weapon, especially for troops in Afghanistan where insurgents have long been employing marksman rifles, mortars, and their own recoilless rifles to out-range American and other coalition forces, the Army has dragged its feet on the idea of buying the M3E1 in any substantial numbers for years. Much of the rest of the world, including various American allies, would probably find the idea of calling the weapon “new” almost absurd.

The M3E1 is one of the latest versions of a design that dates back to the late 1940s. A Swedish state-run arsenal, Carl Gustafs Stads Gevärsfaktori – literally “Rifle Factory of Carl Gustaf’s town” – made the first versions, leading many to nickname the weapon the Carl Gustaf or Carl G, a moniker that persists to this day. In 1991, Bofors bought and privatized the national company, which had existed in one form or another since 1812. In 1999, Saab bought Bofors’ parent company Celsius Group and renamed the firm Saab Bofors Dynamics, which continued to build and improve on the recoilless rifles.

There are a number of good reasons why the Carl G has stood the test of time, mainly its durability, reliability, and versatility. Though the Swedish developed the man-portable weapon initially to take out tanks, it quickly became apparent that it could blast bunkers, buildings, and enemy forces hunkered down behind other hard cover. A standard high explosive round was effective against light vehicle and troops in the open, too.

And while inspired in part by the appearance of the American M1 and M9 Bazookas and the German Panzerschreck shoulder-fired rocket launchers during World War II, the Carl Gustaf used the older recoilless principle. This meant that the weapon could send relatively large projectiles flying at far faster speeds than a rocket launcher, but still be safe for an individual to shoot, even standing up. The Korean War and Vietnam-era U.S. military M20 Super Bazooka fired rockets that had a top speed of approximately 340 feet per second. By comparison, depending on the type of ammunition, the Swedish weapon can fire rounds that travel at over 800 feet per second.

Unfortunately, this power came at the price of weight. The Super Bazooka weighed approximately 15 pounds, less than a contemporary M60 light machine gun. The M3 Carl G, which entered production in 1991, was still 22 pounds after decades of work to trim down its weight. American troops had also recognized the relative benefits and many infantry units began using a recoilless rifle, the 90mm M67, in the early 1960s. This weapon tipped the scales at more than 37 pounds.

Man portable guided anti-tank missiles were supposed to settle the argument once and for all and by the early 1990s, most U.S. Army units had finally retired the M67. The service’s infantry units also had single-shot M72 Light Anti-tank Weapon (LAW) rocket launchers, until the 1980s, when the aforementioned AT4 entered service. The AT4, also known as the M136, is a recoilless rifle and is essentially a single-shot Carl G.

The Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment had kept its M67s, understanding their value as an alternative to disposable anti-tank weapons and missiles. In 1988, the Rangers had finally decided to replace these bulky weapons with the lighter weight Carl Gustav M3, dubbing it the Ranger Anti-Armor/Anti-Personnel Weapon System, or RAAWS. Other special operations forces saw how useful the recoilless rifles could be and it spread rapidly to Army Special Forces and U.S. Navy SEAL elements, ending up known as the Multi-Role Anti-Armor/Anti-Personnel Weapon System, or MAAWS.

In conventional units, though, the combination of missiles and AT4s continued for more than a decade. It’s what Army soldiers had when they deployed to Afghanistan for the first decade of that seemingly never ending conflict. Most American troops also had 5.56mm M16 rifles, M4 carbines, and M249 squad automatic weapons.

The 5.56mm’s limited range and stopping power at long distance is something we at The War Zone have discussed in depth before. In May 2017, I wrote:

“In Afghanistan more so than Iraq, insurgents employed Soviet-era 7.62x54mm SVD rifles, RPGs, recoilless rifles, and mortars and seemed to routinely out-range American squads armed primarily first with M16s and then the shorter M4 carbine. Though handier for close-quarters combat and when getting in and out of vehicles, the M4’s 14.5-inch barrel only reduced the terminal impact and effective range of the 5.56mm bullet.

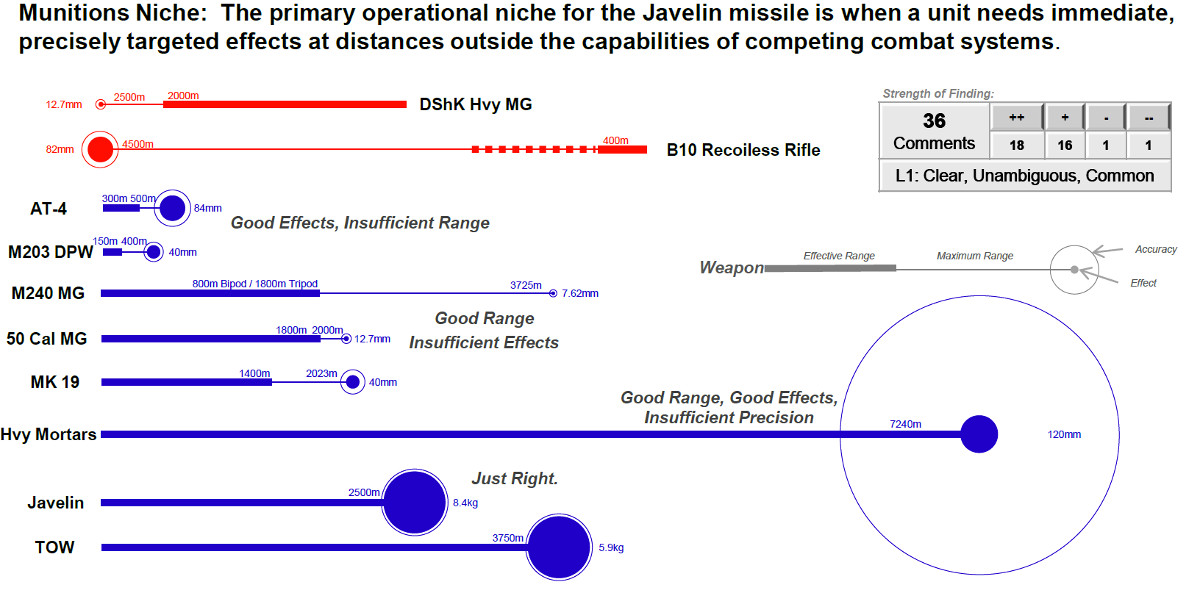

“Things were bad enough that troops had taken to firing expensive Javelin anti-tank missiles at enemy fighters in order to hit them from a safe distance and get at them behind hard cover, such as rock outcroppings and earthen barriers.”

The use of Javelin in particular had become so pronounced by 2012, that Jerry Schlabach, who performed operations research, modeling, simulation, and analysis for the manufacturer Raytheon, briefed the National Defense Industry Association’s annual Joint Armaments Conference on the topic. The powerpoint slides included quotes from troops who had fought in Afghanistan lauding the missile’s ability to break up ambushes, get at insurgents hiding in caves and behind hard cover, and even perform a limited surveillance function thanks to the launch control unit’s infrared optic.

“They [the Taliban] got an 82 [mm recoilless rifle], and they like using it because they can be like, a frickin’ thousand meters away and hit almost every time, what they’re aiming at,” one individual said according to the presentation “It’s a very simple point, click heavy weapon that we have no answer to, except for the Javelin. You know what I mean?”

“Once you get them backed into a cave, … you can drop 120s [120mm mortar rounds] right on top of these things, … but these dudes will come out of that just fine, later on,” another explained. “So we found out that the Javelins, you could fire straight into the mouth of a cave, …it would just blast out the inside of that cave. … and it was perfect.”

It wasn’t perfect, though. Far from it. There was no question that the Javelin could take out insurgents behind cover or inside caves, but every shot was costing the Army $80,000. The most expensive 84mm rounds for the Carl Gustaf cost approximately $3,000 each.

The service was well aware of the situation, the need for a cost-effective solution, and its readily available options. In 2011, someone managed to dig out a number of old M67s and 90mm ammunition from storage somewhere and send it all to Afghanistan along with members of the 4th Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division.

In what should have been a surprise to no one, troops were thrilled even with the dated weapons. They offered small infantry unit both added range and flexibility against a wide variety of targets thanks to an array of different rounds and that they weren’t single use like the AT4. Soldiers were particularly impressed with M67’s own flechette anti-personnel round.

Conflicting budget priorities and cuts, thanks to a process known as sequestration that came into effect after Congress passed the Budget Control Act in 2011, continued to slow the process of picking the most obvious solution, the Carl Gustav. The steady drawdown of American troops in Afghanistan, the main theater where there was an identified and immediate need for such weapons, didn’t help matters any.

To give a sense of how long the Army has been considering fielding the weapon on a broad scale, in December 2011, it piggy-backed on a U.S. Special Operations Command contract to buy less than 60 of the recoilless rifles for field tests. What’s changed actually has more to do with events halfway around the world from Afghanistan.

In 2014, Russian troops seized control of Ukraine’s Crimea region and began lending direct support to separatists in that country’s eastern regions. The Kremlin began to adopt a more revanchist foreign policy in general and NATO responded by increasing its posture along the alliance’s borders with Russia.

Since then, the Army has become increasingly concerned about its ability, or potential lack thereof, to fight a so-called near-peer opponent with a large conventional military. Modernizing the service’s anti-armor capabilities in particular, something almost entirely unnecessary for operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, soon became a priority.

By 2016, the Army had made clear it was finally moving ahead with the plans to field the Carl Gustav to conventional forces. But at the same time, the conflict in Afghanistan had gone in a new and worrisome direction and needs of American troops there gained renewed attention.

“Our original investment of $3 million has led to an approximate $40 million procurement for the Army, which is a great return on investment,” Everett, the FCT project manager, explained in September 2017. “But, most importantly, the M3E1 can be reused so it gives Soldiers increased flexibility and capability on the battlefield.”

The Army isn’t the only service that is seeing potential in the weapon, either. The U.S. Marine Corps, which has employed a reloaded rocket launcher, the Mk 153 Shoulder-Launched Multipurpose Assault Weapon (SMAW), since 1984, is looking to replace some or all of those weapons with the M3E1, too. Earlier in October 2017, Marines trained in Japan on the weapon system.

Now the weapon finally appears to be gaining traction within the U.S. military, especially with the large, urgent Army purchase, it seems that the Carl Gustaf is set to become an increasingly important part of American infantry operations for years to come.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com