As part of a slew of new small arms developments, the U.S. Army wants contractors to submit designs for a possible replacement for the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) called the Next Generation Squad Automatic Rifle (NGSAR). Now, the service has confirmed what it really wants, if possible, is a universal system that can replace a variety of different guns, an ambitious idea that has failed to produce results in the past.

On May 31, 2017, the Army posted a special notice on FedBizOpps, the federal government’s main contracting website, announcing plans to hold classified meetings with defense contractors about the NGSAR and solicit proposed designs for the gun. At one of those gatherings, someone asked whether the final weapon would only end up replacing the M249 or if it might end up taking up other roles.

The Army posted its answer online, along with responses to other questions from industry representatives, on Aug. 10, 2017. “The Government has a decision point in [Fiscal Year 2019] to determine if the NGSAR will be able to fulfill additional roles such as that of the squad designated marksman, medium machine gun, and the carbine,” it explained.

This means, the final gun, or specific versions thereof, could ultimately supplant the standard M4 carbine, precision rifles like the M110 or its own near-term replacements, and even some members of the M240 general purpose machine gun family, including the lightweight M240L.

This is a significant change from basic description in the original announcement, which only made reference to replacing the M249. At present, there are two of the belt-fed SAWs in each of the Army’s infantry squads, which allow them to lay down a high volume of fire in both offensive and defensive operations.

In its initial posting, the Army said it wanted the notional NGSAR to be able to hit and kill stationary targets or suppress moving targets at ranges of at least nearly 1,970 feet and possibly more than 3,900 feet. The specific accuracy requirements were classified.

The proposed guns couldn’t be any more than 12 pounds, unloaded, with a desired weight, if possible, of approximately 8 pounds. With a full-length barrel and standard fixed buttstock, the M249 weighs in at approximately 17 pounds. The Army has already issued shorter barrels and lighter stocks to help lighten the gun.

Submitted designs had to be 38 inches long, or less, and feature a folding buttstock that would shorten the gun down to at least 35 inches. There was a goal of eventually getting those dimensions down to 35 inches long overall and 32 inches with the stock stowed away. The full-sized M249 is nearly 41 inches from end to end.

Most notably, the Army’s main ammunition requirement was that the load be at least 20 percent and possibly up to 50 percent lighter than the “tactical brass equivalent” of whatever caliber the submission was set up for. “Note the NGSAR ammunition could be a caliber not currently in use by the U.S. Army,” the notice said.

This opened up the possibility that the weapon could use a so-called “intermediate round,” generally understood to have characteristics that fall somewhere in between those of the 5.56x45mm cartridge that the M249 uses and larger rounds, such as the 7.62x51mm. When the NGSAR announcement came out, the Army was already in the process of developing just such a projectile as part of a separate project to find a replacement for the M4, which is also chambered for the 5.56x45mm cartridge.

Beyond that, the new squad automatic rifle would need a sound suppressor and the ability to accept a host of standard Army accessories, such as optical sights and laser aiming devices. The service stipulated a variety of basic cost and reliability parameters, as well.

Though the service made clear it was still in the process of gathering information and had no formal plans to buy any weapons as yet, it said it wanted to begin phasing out the M249s in infantry units sometime in the 2020s. This was apparently a stepped up time frame from the initial development plan.

According to Military.com, the Army originally categorized the NGSAR as a “mid-term goal,” which would enter service sometime between 2026 and 2035. “That may be accelerated into the near term as we plan on fielding that first unit equipped in by 2025,” U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Loyd Beal III, the Product Manager for Crew Served Weapons, told the outlet in May 2017 before the release of the NGSAR notice.

But there were already hints in the original announcement that the proposed gun might be more than just an M249 substitute, which may have been what provoked the contractor’s question in the first place. The NGSAR “will combine the firepower and range of a machine gun with the precision and ergonomics of a carbine, yielding capability improvements in accuracy, range, and lethality,” the notice on FedBizOpps read.

The idea of using one gun for a variety of functions makes perfect sense, at least in theory. Having soldiers using the same weapons and ammunition reduces maintenance, logistics, and training requirements. A single family of carbines, automatic rifles, and machine guns that share a significant number of common parts would have similar benefits.

But this has proved to be an overly ambition goal in the past. During the development of what became the M60 light machine gun in the 1950, the Army’s plan was to craft a weapon to replace squad’s existing automatic rifles, aging submachine guns, and a host of World War II-era light and medium machine guns. This didn’t work out and the gun served alongside a variety of weapons in infantry units well into the 1980s.

The Army similarly thought that it could use the original M16A1 as both an infantry rifle and squad automatic rifle. Individuals designated for the latter role received a clip-on bipod. The volume of fire from a 5.56mm rifle with a 20 round magazine turned out to be less than impressive.

The M249 itself was, in many ways, an attempt to make up for these previous failures. Hoping to take advantage of a common weapon, the Army wanted the SAW to give automatic rifleman significantly more firepower and replace the M60 with a gun that used the same ammunition as its standard infantry weapons. Unfortunately, the 5.56mm cartridge simply didn’t have the range or terminal ballistics to meet the requirements of a true light machine gun and the service bought 7.62mm M240s instead.

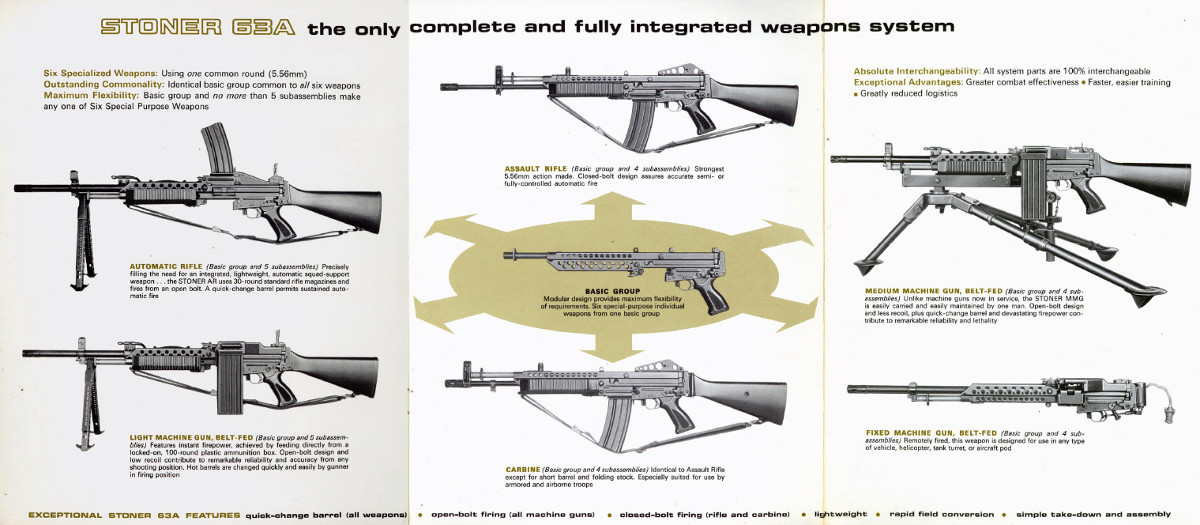

In search of this universal gun, the Army, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps, both experimented with the modular Stoner 63A family of weapons during the 1960s. With a design based around a common central frame, armorers could readily reconfigure this 5.56mm gun into a rifle, carbine, magazine-fed squad automatic rifle, belt-fed light machine gun, and even a fixed version for use on armored vehicles and aircraft.

Both services were pleased with how the guns performed in field tests, but couldn’t justify the cost of replacing thousands of existing 5.56mm M16s so soon after their own introduction with another weapon in the same caliber. Soldiers and Marines weren’t going to be reconfiguring their guns in the field anyways, so the extreme modularity was impressive, but of debatable functional utility.

The U.S. Navy SEALs became the most prolific users of the system, with a hybrid configuration that combined the belt-feeding system with a special short, heavy barrel. In many ways the resulting Mk 23 Mod 0 machine gun can be seen as a predecessor to the M249. The Navy’s Special Warfare community began replacing these aging guns in the late 1980s with a mixture of specially configured derivatives of the M60 and M249.

The Army tried to develop a similar universal infantry weapon system yet again 1990s. As part of a project primarily aimed at replacing the M16 rifle and M4 carbine, Heckler and Koch proposed additional versions of its XM8 rifle for designated marksman and light support roles. This plan too fell through after the service decided that the new guns didn’t offer substantial enough benefits over the existing M16-pattern weapons.

A new system firing an intermediate cartridge would get past the most glaring hurdle of a weapon chambered 5.56mm simply not having the range or terminal effects to act as a true light or medium machine gun. However, the next question becomes whether the resulting system would still be small and light enough to be suitable for basic infantry roles, especially in a compact carbine format.

Interchangeable barrel lengths, as found on the FN SCAR rifle, would be one relatively simple option. Using a drum magazine or similar readily detachable, high capacity feeding mechanism might work for quickly moving from a basic rifle or carbine to a squad automatic weapon or light machine gun role.

The Army could easily look at what the Marine Corps’ is doing with the aforementioned M27 IAR, a design that in many ways already seems to fit very well with many of the NGSAR’s basic requirements. Heckler and Koch’s take on the AR-15/M16 platform, the M27 most notably uses a gas-piston to function rather than the original direct-impingement system, which bleeds off propellant gas to cycle the mechanism introducing potentially problematic particulate matter straight into the gun’s inner workings.

Originally purchased as a substitute for the M249, in 2016, the Marines began looking at expanding the M27’s role, with the possibility of using it as a standard infantry rifle. On top of that, the service has been testing quad-stack 40-round box magazines and 60-round drums to give the IAR more sustained firepower than it presently has with the standard 30-round magazine for the M4.

Advances in lightweight ammunition, such as caseless or cased-telescoped ammunition could help keep the weapons overall length and weight down, while still providing improved capabilities over a standard 5.56mm cartridge, as well. However, these developments have long proved troublesome themselves and, as it stands now, the Army is focused primarily on just lightening ammunition weight with polymer or metal alloy cartridge cases.

The big question at the end of the day will be just how much modularity the Army decides it really needs. Troops are unlikely to be swapping configurations in the field. It might not make sense to try again to craft this so far elusive single universal weapon system if the service can find appreciable amount of cost-saving commonality elsewhere in the maintenance and logistics pipelines.

With this potential requirement in mind, however, it will be very interesting to see what gun makers put forward in their submissions for the NGSAR project.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com