Members of the U.S. Senate want to add more than billion dollars to the annual defense budget for a fleet of light attack aircraft, most likely for the U.S. Air Force. The proposal could push the service to finally buy a type of plane it desperately needs, which might spur action in other branches, as well.

After a long day of deliberations on June 28, 2017, the Senate Armed Services Committee passed an initial vote on their proposed defense budget, clearing one of the first hurdles toward the bill becoming law. An executive summary gave basic details on its contents, which included an authorization of $1.2 billion for “a fleet of Light Attack/Observation aircraft.”

The statement did not provide an estimate of how many airframes the budget would pay for or offer any details about the aircraft requirements or the intended recipients. This funding is not readily apparent in any part President Donald Trump’s original U.S. military spending request, which the Pentagon unveiled in detail in May 2017, but the Senators did not say this item was in addition to those plans. The Senate Committee’s overview included a note in all other instances where it added money over the Trump Administration’s plans. A similar requirement is not present in any of the services’ unfunded priorities “wish lists,” either.

The most obvious answer is that this budget line creates a funding stream for whatever aircraft comes out on top of the Air Force’s light attack aircraft experiment, more commonly known as OA-X. In July 2017, the service expects to begin evaluating at least three different planes – Sierra Nevada Corporation’s (SNC) and Embraer Defense & Security’s A-29 Super Tucano and Textron Aviation’s AT-6 Wolverine and Scorpion – at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. There is always the possibility that other firms will get invitations to join the tests, too.

On top of that, in January 2017, Senator John McCain, an Arizona Republican who just so happens to be chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, released a white paper titled “Restoring American Power.” It recommended purchasing a fleet of 300 “low-cost, light-attack fighters that would require minimal work to develop,” with the first 200 entering service by 2022. “These aircraft could conduct counterterrorism operations, perform close air support and other missions in permissive environments, and help to season pilots to mitigate the Air Force’s fighter pilot shortfall,” McCain explained.

Based on existing cost data, the $1.2 billion figure fits in well with this earlier proposal. The Pentagon has already helped purchase A-29s for the air forces of Afghanistan and Lebanon, with each aircraft costing approximately between $10 and $15 million. These deals have all included various spare parts, support services, training courses, and other ancillary items, meaning the exact cost of the planes specifically has not been immediately apparent, but more than a billion would easily cover a full fleet of dozens of aircraft.

The Senate plan makes perfect sense. For years, the Air Force in particular has been fighting a string of low-intensity conflicts against opponents with limited air defense capabilities primarily using high-performance aircraft, including multi-role fighter jets, as well as drones. This has proven to be an expensive proposition and taxing on an already strained fighter force, as Senator McCain noted in his white paper. But for nearly a decade the service only gave lip service to the idea of buying light attacker to fly these missions on the cheap.

That institutional mindset seemed to be changing earlier in 2017. OA-X could be “a more sustainable model for the future that would be less costly [and] that I could entice foreign partners and allies and coalition members to partner with us on,” U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff General David Goldfein explained during a talk at the American Enterprise Institute on Jan. 18, 2017.

Still, the Air Force has made it abundantly clear it has no clear goal for the OA-X experiment or existing idea of how it might integrate any “winner” into its existing force structure. The project is “is not a procurement, it’s an experiment,” Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson said during a talk at the Air Force Association Forum in Washington, D.C. on June 5, 2017. A defense budget that funds a light attack fleet could be the prompt service needs to actually lay out a coherent plan for how OA-X becomes a fully fledged procurement program.

There are, unfortunately, risks with this strategy, as well. The Senate only needs to look at the outcome of the Light Attack/Armed Reconnaissance (LAAR) program. After individuals within Air Combat Command, the Air Force’s main warfighting command, drafted the initial OA-X concept in December 2008, the service had begun budgeting for this fleet of approximately 15 light attack aircraft, before bringing the project to an inglorious halt in 2012. A big part of why this happened had to do with budget cuts and the process known as sequestration, which imposed caps on defense spending. Contract squabbles were another factor, which also threatened to scuttle a parallel project to send similar planes to Afghanistan – which did ultimately result in purchases of A-29s.

However, even if the Air Force had overcome these hurdles, it had no idea where the light attackers would go. Federal statutes and internal rules meant units tasked with training foreign air forces, such as the 6th Special Operations Squadron, were the only ones who could do the job the service intended for the aircraft. But with a host of non-standard planes already, they weren’t particularly interested. Air Combat Command did have a certain level of interest, but had no authority to fly them. In addition, it wasn’t entirely clear where the personnel for the new squadron would come from or who would ultimately pay for its upkeep.

If the Air Force doesn’t rise to the Senate’s new proposal, this new OA-X fleet could end up “homeless” within the service just like the proposed LAAR aircraft. A similar situation arose with the C-27J airlifter, all of which ended up horse-traded to U.S. Special Operations Command, the U.S. Coast Guard, and the U.S. Forest Service.

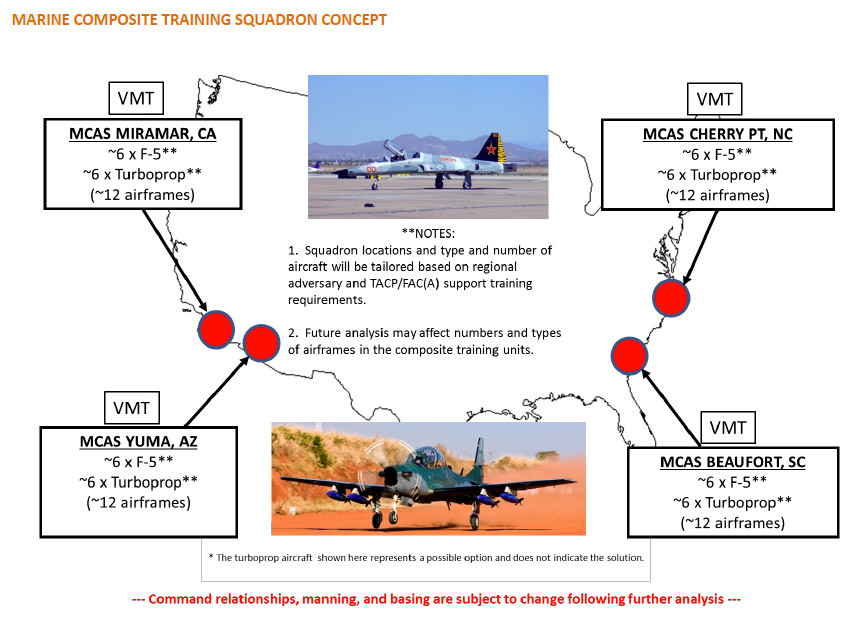

However, if the program does run into problems, the Air Force could work with other services to share the burdens and keep things moving forward. For years now, the Marine Corps has considered creating a composite training force that includes a similar type aircraft. Its concept has the planes helping tactical air controllers on the ground and forward air controllers in the air practice calling in and coordinating close air support missions. The existing plans do not include a combat role for these planes at present.

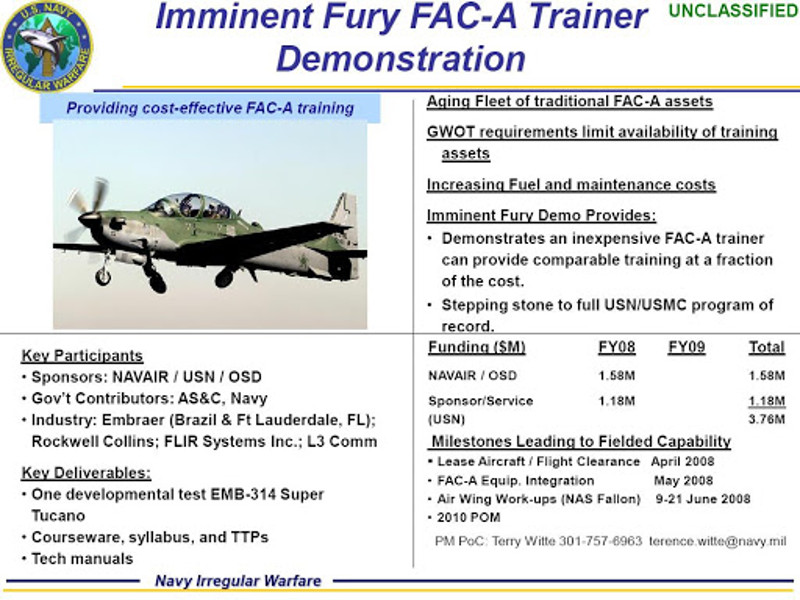

First mentioned in the Corps’ 2016 master aviation plan, the idea reappeared in the 2017 version. However, the Marines have been interested in this concept since at least 2009, when the Navy coordinated a similar demonstration program nicknamed Imminent Fury involving a Super Tucano. That project subsequently transitioned to a special operations light attack experiment, ultimately resulting in the deployment of a pair of modified OV-10 Bronco aircraft to fight ISIS in Iraq in 2015. As The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway wrote in March 2017, the Marine Corps training program could be a stepping stone to a broader, deployable light attack capability within the service, as well as the U.S. Navy.

A joint Air Force-Navy-Marine Corps OA-X program might actually make the most sense in both the short and long terms. It would help share the burden of paying and manning the resulting units and give the Air Force space to develop plans to absorb its share of the aircraft. At the same time, the Marines could leverage the Air Force’s own experience working with these types of aircraft in cooperation with Afghanistan and Lebanon, which includes both pilot training and managing logistics chains.

Of course, the Senate Armed Services Committee’s spending proposal is just that and not guaranteed to become law in its existing form. But with the extra push from members Congress, who clearly support this cost-effective idea, the U.S. military could finally move toward fielding a real and valuable light attack capability.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com